When I was young, I remember hearing the hypothesis that cell phone radiation was harmful. I remember my younger brother, having concern towards me and the family lineage, making a big deal about me placing my cell phone in my pocket, near the family jewels. This idea, of the harm of non-native electromagnetic fields (nnEMF) has existed in our culture for a while, yet we do not commonly give it credence or attention. It is as if we all are unsure whether it is true, and even if it was true we are hopeless to fix it. Perhaps we avoid the subject because it is so uncomfortable. This worry exists somewhere within our culture though, and yet we rarely treat it as a scientifically valid concern worthy of objective inquiry. However, this is by no means indication that these waves are harmless. In fact, research has existed for decades that they are.

To begin, it is best we define what nnEMF is. Electromagnetic fields (EMF) are all around us and are fundamental to nature and the laws of physics. An electromagnetic field (EMF) is a space where electric and magnetic forces exist together, produced whenever electric charges (like electrons) move. In nature, things such as lightning, ocean currents, and the Earth’s magnetic field constantly generate tiny EMFs. For example, the Schumann resonance is a natural EMF, it is a low‑frequency wave of around 7.8 Hz, created by the massive electron flows of lightning that bounce between the conductive ground and the conductive ionosphere.

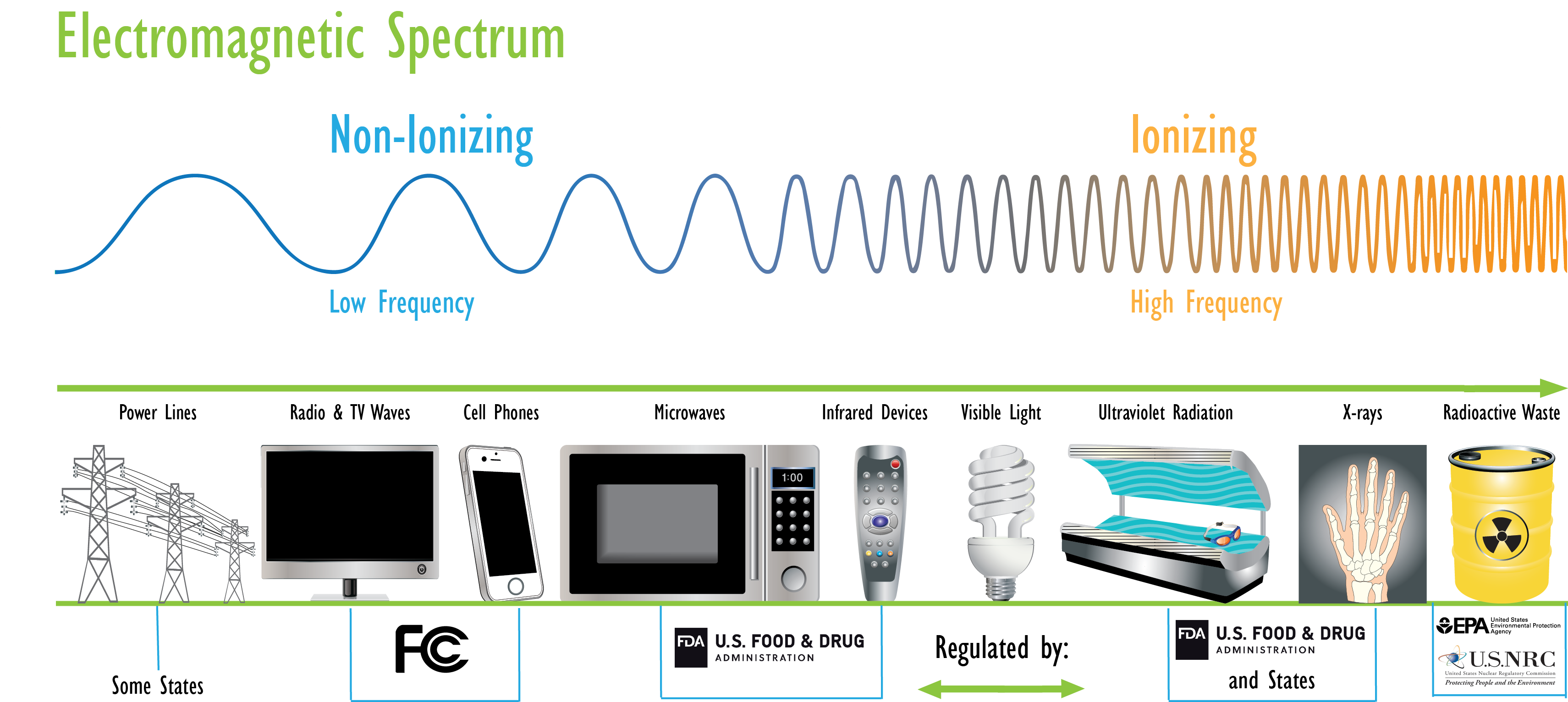

Visible light is also electromagnetic radiation composed of electromagnetic waves, and our bodies have evolved in an environment filled with many naturally occurring, visible and non‑visible electromagnetic fields. Non-native EMF (nnEMF), then, are unnatural waves produced from our technology. They are not native to our natural environment or biology. Below is an image of the spectrum of electromagnetic frequencies and their corresponding devices (Image sourced from NASA):

The health implications of nnEMF are usually categorized by the frequency (or energy) of the radiation. Ionizing radiation, with short wavelengths and high photon energy, can ionize atoms and molecules, break chemical bonds, and lead to physiological damage. Classic examples include alpha, beta, gamma, and X‑rays emitted during radioactive decay. These types of waves have been recognized as harmful without dispute. Non‑ionizing radiation lacks sufficient photon energy to directly break chemical bonds, and for this reason has been regarded as safe at typical environmental levels. Below is another chart that illustrates the sources of the two types of nnEMF (Image sourced from the EPA):

While the non-ionizing radiation of our technology-filled environment does not affect our bodies in the same way ionizing radiation does, there is research to suggest that it does harm our health in a different way. It effects our cells in a way that was not initially intuitive. Nonetheless, there is decades of research showing that these nnEMF influence our health in negative ways.

While the non-ionizing radiation of our technology-filled environment does not affect our bodies in the same way ionizing radiation does, there is research to suggest that it does harm our health in a different way. It effects our cells in a way that was not initially intuitive. Nonetheless, there is decades of research showing that these nnEMF influence our health in negative ways.

Some of the earliest research regarding the negative health effects of nnEMF was conducted in the 1970s. In 1975, Allan Frey, and others, conducted an experiment where they subjected rats to radio-frequencies (RF) of 1.2GHz after injecting their bloodstream with a dye (Allan H. Frey, Sondra R. Field, and Barbara Frey Feburary 1975). They found that the rats that were subjected to the nnEMF had the ink-dyed blood in their brain, suggesting that the radiation exposure caused leakage to the blood-brain barrier. In 1976, Suzanna Bawin, and others, conducted experiments on chicken and cat brains, where they were placed into a solution and found that frequencies of 1, 6, 16, 32, and 75 Hz led to the brain cells retaining more calcium (Bawin and Adey 1976). A follow‑up study suggested that low‑frequency waves (1–30 Hz) affect calcium movement in cells by interacting with negatively charged binding sites on the outer surface of the plasma membrane, thereby causing calcium to be released into the extracellular fluid (Bawin, Adey, and Sabbot 1978). These studies paved the way for research to begin investigating how nnEMF influence cellular function. There was another study, conducted in 1994, that similar showed frequencies of 915 MHz increased blood-brain barrier permeability (Salford et al. 1994). While increased blood-brain barrier permeability can be incredibly detrimental to one’s health, the most notable consequence of nnEMF uncovered in these early studies may be the effects they have on cellular calcium levels.

Years go by, and several studies are conducted. By 1991, a review of 10 studies claims that there is ample evidence amongst the scientific literature that frequencies below 100 Hz change calcium permeability of cells (Walleczek 1991). The human body, and the cells within it, depend on precise ion and electric charge gradients across membranes for normal function. For example, the movement of calcium across neuronal membranes greatly influences the activation and proper functioning of neurons (Berridge 1998). Maintaining these ionic balances is essential for cellular health, and any artificial disturbance could profoundly affect our cells. Emerging evidence suggests that nnEMF can alter calcium concentrations across cell membranes, and it’s crucial to consider how such influences might impact overall health, particularly mitochondrial function.

Mitochondria, commonly known as the ‘powerhouse’ of the cell, are what give our cells energy, allowing for the more complex processes that led to the complex biological life we see on Earth. ATP is produced within the mitochondria via oxidative phosphorylation which includes two steps: the electron transport chain and chemiosmosis. The electron transport chain is where electrons provided by the glucose from our food, combined with the oxygen we breathe, produces a proton gradient across the membrane of the mitochondria, and results in the production of water. The proton gradient produced subsequently allows a protein complex named ATP synthase to produce ATP, the molecule for energy use in the body.

Up until very recently in human history, the most common cause of death was from diseases that were communicable. Given the rise of modern medicine, many of these diseases are treatable. However, in the 1900s, a shift also occurred where non-communicable disease became, by a large margin, the leading cause of death (O U et al. 2015). Leading causes of death today include diabetes, cancer, obesity, and respiratory disease (O U et al. 2015). Unlike our historical past, the way society alleviates this burden of disease is likely not by being hostile toward a pathogen. It may require having humility in appreciating how our modern lifestyles are out of sync with nature. For example, our modern lives create busy brains, and we accordingly no longer have minds characterized by mindfulness, which is a state of mind more akin to life in nature which has the capability of reducing overall chronic disease (Zhang et al. 2021). At the physical level, what is at the root of our chronic disease is the health of our mitochondria. With energy, utilized via ATP, the body is not capable of effectively performing the physiological processes needed for healthy function. By way of analogy: no matter how many good resources you provide a factory, without energy, there is no production. Mitochondrial health is at the center of our chronic disease (Gonzalez, Miranda-Massari, and Duconge 2014; Phillips et al. 2019). Below is an illustration of the structure of mitochondria:

Image: Submitochondrial particle by Aeffenberger. Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-SA 4.0).

Mitochondria have two layers. There is an outer membrane, and there is another membrane which houses the matrix where cellular respiration takes place. The outer membrane is very porous and allows for both small ions and large molecules to pass through, however the inner membrane is very selective and tightly controls the flow of ions such as potassium (K+), sodium (Na+), and calcium (Ca2+), and various molecules involved in cellular respiration (Bayrhuber et al. 2008; Kühlbrandt 2015). Again, the controlled gradients of charged ions on either side of a membrane are central to how cellular processes work. Consequently, ion concentrations within the cell’s cytoplasm can dramatically impact the health and functioning of a cell. Recent research indicates that the mitochondria act as a calcium sink within the cell, finely tuning the calcium levels within the cell by absorbing and releasing calcium, as appropriate (Sullivan et al. 2005; Rizzuto et al. 2012).

However, if something were to cause an unnatural influx of calcium into the mitochondrial space, the mitochondrial permeability transition pore mPTP will open up and lead to the release of mitochondrial calcium, and other molecules, into the cell’s cytoplasm (Sullivan et al. 2005). This dysfunctional event leads not only to mitochondrial uncoupling and decreases ATP production, but can also lead to the release of Cytochrome C into the cell which could trigger premature cell death (Sullivan et al. 2005; Duchen 2000; Kroemer and Reed 2000). In other words, it is possible that the unnatural saturation of nnEMF lead to too much calcium in the mitochondria, leading to a dysfunctional calcium content regulator inside cells which results in decreased energy production or cell death.

This proposed mechanism could go to explain the observed harms our modern devices can potentially cause to our health. For example, a review of research hypothesized that this alteration of voltage-gated calcium channel activity from nnEMF causes an assortment of psychiatric disorders, including depression (Pall 2016). It may also help explain why a case study in 2013, that involved self-reports of cell phone use, found that increased use of cell phones was correlated to an increase in brain tumors (Hardell et al. 2013). There has also been a smaller case study correlating occupational exposure to nnEMF and an increased risk of Alzheimer’s (Sobel et al. 1995). An even older study, conducted in the 1980s, found that there was a seasonal difference in pregnancy success, suggesting that the increased use of heated beds and blankets during winter time negatively influenced the pregnancy process (Wertheimer and Leeper 1986).

While research has existed for decades that suggest there are negative health effects from nnEMF, and this exists alongside proposed mechanisms that also have existed for decades, it is curious to wonder why this subject is so rarely discussed. Furthermore, because this field of research is understudied, this article may be just scratching the surface on the harms of nnEMF and the various consequences it has on our mitochondria and health. Throughout history, we have invented technologies. Sometimes, we invent technologies that turn out to be harmful, and we are smart to change course. Our modern devices are essential to the functioning of our modern lives. If they are truly as harmful as the research presented here suggests, it would be very prudent that we all do our best to change course in a way that optimizes both our health and our society. References

- Allan H. Frey, Sondra R. Field, and Barbara Frey. Feburary 1975. “Neural Function and Behavior: Defining The Relationship.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 247 (1)https://ehtrust.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/07/FreyPioneeringPapers.pdf.

- Bawin, S. M., and W. R. Adey. 1976. “Sensitivity of Calcium Binding in Cerebral Tissue to Weak Environmental Electric Fields Oscillating at Low Frequency.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 73 (6): 1999–2003.

- Bawin, S. M., W. R. Adey, and I. M. Sabbot. 1978. “Ionic Factors in Release of 45Ca2+ from Chicken Cerebral Tissue by Electromagnetic Fields.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 75 (12): 6314–18.

- Bayrhuber, Monika, Thomas Meins, Michael Habeck, Stefan Becker, Karin Giller, Saskia Villinger, Clemens Vonrhein, Christian Griesinger, Markus Zweckstetter, and Kornelius Zeth. 2008. “Structure of the Human Voltage-Dependent Anion Channel.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 105 (40): 15370–75.

- Berridge, M. J. 1998. “Neuronal Calcium Signaling.” Neuron 21 (1): 13–26.

- Duchen, M. R. 2000. “Mitochondria and Ca(2+)in Cell Physiology and Pathophysiology.” Cell Calcium 28 (5–6): 339–48.

- Gonzalez, Michael J., Jorge R. Miranda-Massari, and Jorge Duconge. 2014. “The Role of Mitochondria in Cancer and Other Chronic Diseases.” https://www.researchgate.net/publication/311389607.

- Hardell, Lennart, Michael Carlberg, Fredrik Söderqvist, and Kjell Hansson Mild. 2013. “Case-Control Study of the Association between Malignant Brain Tumours Diagnosed between 2007 and 2009 and Mobile and Cordless Phone Use.” International Journal of Oncology 43 (6): 1833–45.

- Kroemer, G., and J. C. Reed. 2000. “Mitochondrial Control of Cell Death.” Nature Medicine 6 (5): 513–19.

- Kühlbrandt, Werner. 2015. “Structure and Function of Mitochondrial Membrane Protein Complexes.” BMC Biology 13 (1): 89.

- O U, Adogu P., Ubajaka C. F, Emelumadu O. F, and Alutu C. O C. 2015. “Epidemiologic Transition of Diseases and Health-Related Events in Developing Countries: A Review.” American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences 2015 (4): 150–57.

- Pall, Martin L. 2016. “Microwave Frequency Electromagnetic Fields (EMFs) Produce Widespread Neuropsychiatric Effects Including Depression.” Journal of Chemical Neuroanatomy 75 (Pt B): 43–51.

- Phillips, Andrew J. K., Parisa Vidafar, Angus C. Burns, Elise M. McGlashan, Clare Anderson, Shantha M. W. Rajaratnam, Steven W. Lockley, and Sean W. Cain. 2019. “High Sensitivity and Interindividual Variability in the Response of the Human Circadian System to Evening Light.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 116 (24): 12019–24.

- Rizzuto, Rosario, Diego De Stefani, Anna Raffaello, and Cristina Mammucari. 2012. “Mitochondria as Sensors and Regulators of Calcium Signalling.” Nature Reviews. Molecular Cell Biology 13 (9): 566–78.

- Salford, L. G., A. Brun, K. Sturesson, J. L. Eberhardt, and B. R. Persson. 1994. “Permeability of the Blood-Brain Barrier Induced by 915 MHz Electromagnetic Radiation, Continuous Wave and Modulated at 8, 16, 50, and 200 Hz.” Microscopy Research and Technique 27 (6): 535–42.

- Sobel, E., Z. Davanipour, R. Sulkava, T. Erkinjuntti, J. Wikstrom, V. W. Henderson, G. Buckwalter, J. D. Bowman, and P. J. Lee. 1995. “Occupations with Exposure to Electromagnetic Fields: A Possible Risk Factor for Alzheimer’s Disease.” American Journal of Epidemiology 142 (5): 515–24.

- Sullivan, P. G., A. G. Rabchevsky, P. C. Waldmeier, and J. E. Springer. 2005. “Mitochondrial Permeability Transition in CNS Trauma: Cause or Effect of Neuronal Cell Death?” Journal of Neuroscience Research 79 (1–2): 231–39.

- Walleczek, J. 1991. “Electromagnetic Field Effects on Cells of the Immune System: The Role of Calcium Signalling.” presented at the 75th Annual Meeting of FASEB, Atlanta, Gerogia, April 24. https://doi.org/10.1096/fasebj.6.13.1397839.

- Wertheimer, N., and E. Leeper. 1986. “Possible Effects of Electric Blankets and Heated Waterbeds on Fetal Development.” Bioelectromagnetics 7 (1): 13–22.

- Zhang, Dexing, Eric K. P. Lee, Eva C. W. Mak, C. Y. Ho, and Samuel Y. S. Wong. 2021. “Mindfulness-Based Interventions: An Overall Review.” British Medical Bulletin. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/bmb/ldab005.