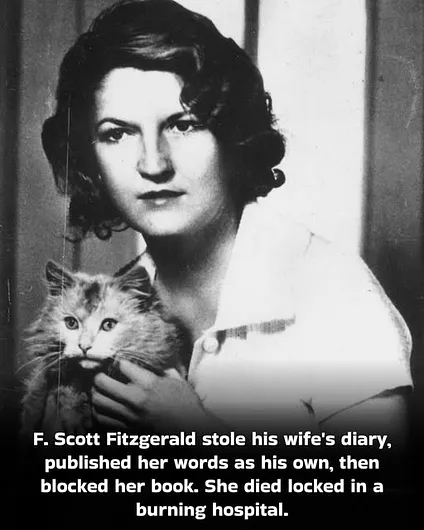

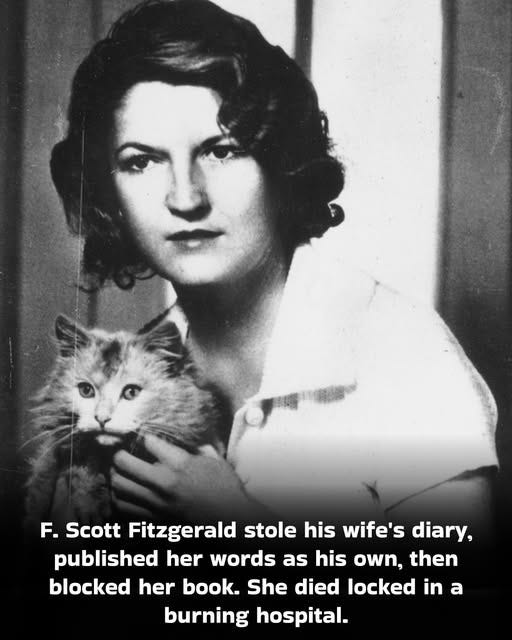

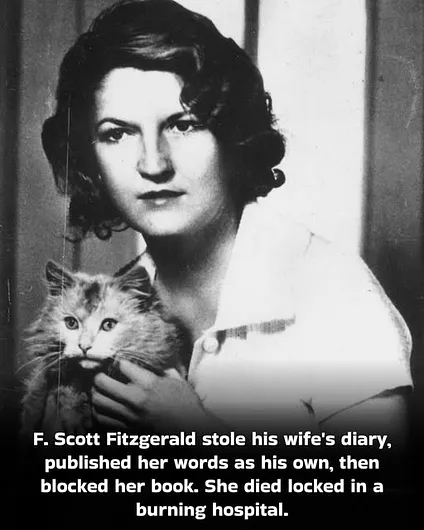

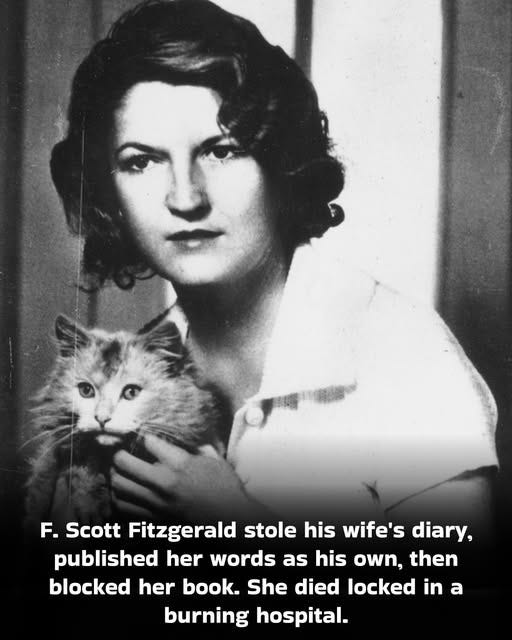

Her name was Zelda Sayre Fitzgerald. And history remembers her as "Scott Fitzgerald's crazy wife."

Montgomery, Alabama, 1918. Zelda Sayre was 18 years old and the most desired woman in the South. She was wild. Scandalous. She smoked in public, wore flesh-colored swimsuits that made her look naked from a distance, drank gin, drove cars fast, and kissed boys without apology. "The most sought-after girl in Alabama," newspapers called her. The belle of Montgomery society who broke every rule and didn't care.

He was 22, unpublished, broke, unknown. She was a Southern beauty who could have any man she wanted. Scott proposed. Zelda said no. Not because she didn't love him—but because she refused to marry a man with no prospects. "I can't marry you unless you can support me," she told him. In 1918, that wasn't shallow. That was survival.

So Scott Fitzgerald made a choice: he would become successful enough to deserve her. He moved to New York, worked in advertising (which he hated), and spent every night writing a novel. When "This Side of Paradise" sold in 1919, he immediately telegraphed Zelda: "BOOK SOLD. MARRY ME NOW."

She did. They married in 1920. She was 19. He was 23. And for a few years, they were the golden couple of the Jazz Age. Scott's novels made them rich and famous. They lived in New York, partied with celebrities, spent money recklessly. They jumped into fountains, rode on the tops of taxis, drank champagne for breakfast. Zelda was electric. Glamorous. Fearless. She cut her hair into a bob—shocking in 1920. She wore short skirts. She said outrageous things at parties. The press loved her. She gave the best quotes: "I don't want to live—I want to love first, and live incidentally."

Scott loved her too. Obsessively. She was his muse, he said. The inspiration for all his great female characters—Daisy Buchanan, Nicole Diver, Gloria Gilbert.

But there was a darker truth: he wasn't just inspired by Zelda. He was stealing from her. Zelda kept personal diaries—intimate, beautifully written accounts of her thoughts, feelings, experiences. Scott would read them, then copy passages directly into his novels. Without her permission. Without credit. In "This Side of Paradise", he lifted entire sections from Zelda's letters and diaries. When reviewers praised the "authentic female voice" in his work, Scott accepted the compliments. When Zelda protested, he dismissed her: "I'm the professional writer. You're just my wife."

When a reviewer praised one passage as "brilliant," Zelda's friend told her: "You know you wrote that, right? That's from your diary." Zelda confronted Scott. He shrugged: "Nobody would read it if you wrote it." Zelda decided to become a writer anyway. Through the 1920s, she published articles and short stories in magazines—Harper's Bazaar, College Humor, The Saturday Evening Post. Her pieces were funny, sharp, insightful. But editors insisted they be published under "F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald"—even when Scott hadn't written a word. His name sold magazines. Hers didn't. The money went to "their" joint account, which Scott controlled. She was writing. Getting published. And still being erased.

Substack

Colin Durrant (@colindurrant)

F. Scott Fitzgerald stole his wife's diary, published her words as his own, then blocked her book.

She died locked in a burning hospital.

Her nam...