Trade Escalation, Supply Chain Vulnerabilities and Rare Earth Metals

Published on October 14, 2025 3:30 PM GMTWhat is going on with, and what should we do about, the Chinese

China Clamps Down Even Harder on Rare Earths

The move is Beijing’s latest attempt to tighten control over global production of the metals, which are essential to the manufacture of computer ...

and also beyond rare earths into things like lithium and also antitrust investigations?

China also took other actions well beyond only rare Earths,

CNBC

China opens antitrust probe into the U.S. chip giant Qualcomm

Qualcomm has a big business in China selling its smartphone chips to some of the biggest players in the country such as Xiaomi.

, lithium and everything else that seemed like it might hurt, as if they are confident that a cornered Trump will fold and they believe they have escalation dominance and are willing to use it.

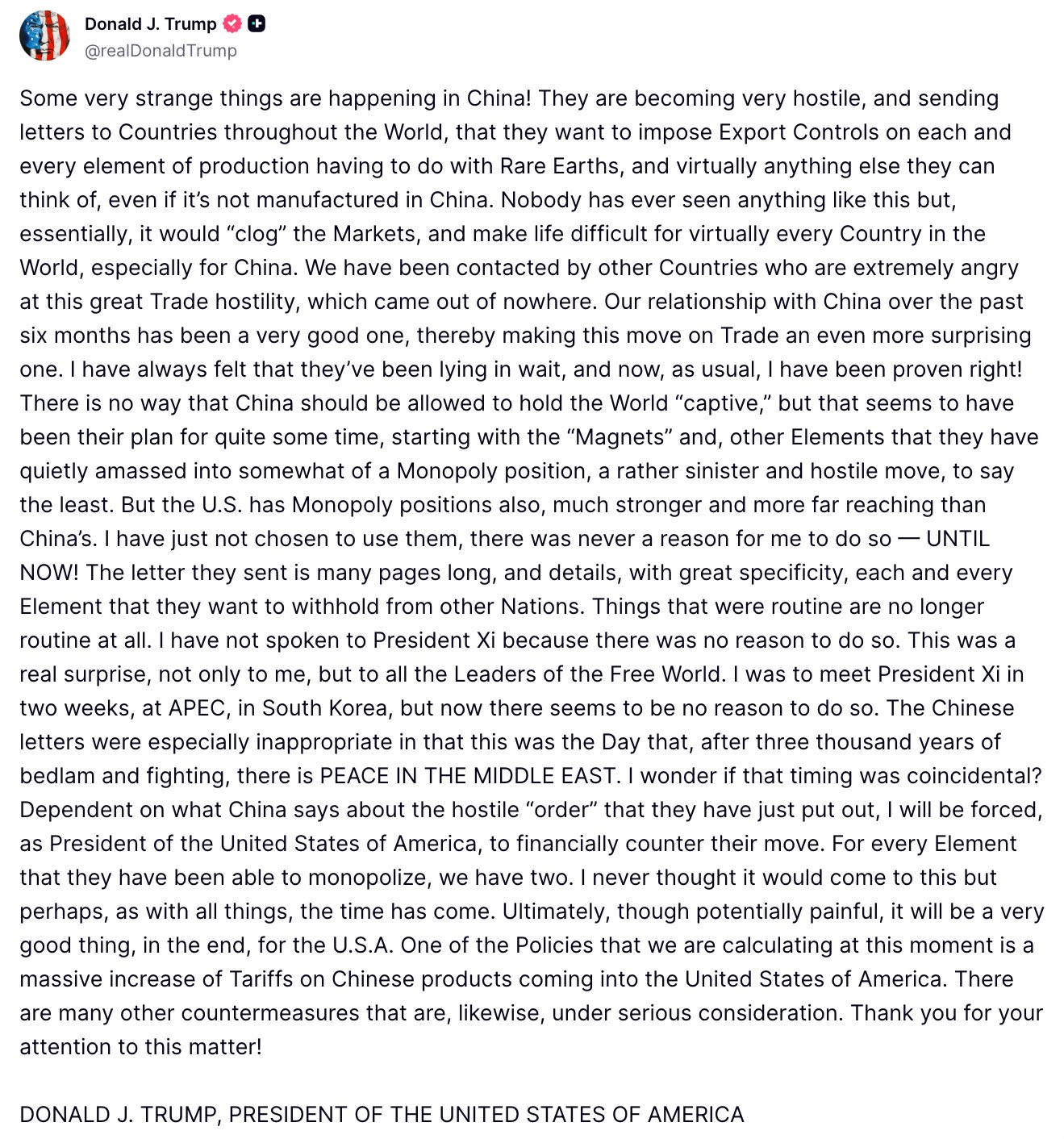

China now has issued reassurances that it will allow all civilian uses of rare earths and not to worry, but it seems obvious that America cannot accept a Chinese declaration of extraterritorial control over entire world supply chains, even if China swears it will only narrowly use that power. In response, Trump has threatened massive tariffs and cancelled our APAC meeting with China, while also trying to calm the markets rattled by the prospect of massive tariffs and the cancellation of the meeting with China.

World geopolitics and America-China relations are not areas where I am an expert, so all of this could be highly misguided, but I’m going to do my best to understand it all.

Was This Provoked?

X (formerly Twitter)

Brad Setser (@Brad_Setser) on X

@pstAsiatech @Lingling_Wei Paul -- that is a serious claim, and I would appreciate your evidence here, as you generally lean against most US contro...

this is in response to a new BIS ‘50% rule’ where majority owned subsidiaries are now subject to the same trade restrictions as their primary owners, or that this and other actions on America’s side ‘broke the truce.’

X (formerly Twitter)

Paul Triolo (@pstAsiatech) on X

@Brad_Setser @Lingling_Wei @briangobosox Brad, I can see you are confused, as are many not working in the private sector. Working with companies e...

and thus this can impose non-trivial costs and cause some amount of risk mitigating action, but I don’t buy it as a central cause. It never made sense that we’d refuse to trade with [X] but would trade with [X]’s majority owned subsidiary, and imposing full extraterritoriality on 0.1% value adds plus taking other steps is not remotely proportionate retaliation for that, especially without any sort of loud warning. If that’s the stated justification, then it’s for something they were looking to do anyway.

If you buy the most pro-China argument being made here (which I don’t),

X (formerly Twitter)

Steve Hou (@stevehou) on X

The best thread on the US-China trade war escalation I’ve read so far.

Fundamentally, this issue comes down to whether one wants to deal with th...

to ‘get tough’ or sabotage the talks, thus making us untrustworthy, then the Chinese response seems quite unstrategic to me.

Whereas the right move if this did happen would have been to loudly call out the moves as having been done behind his back and give Trump a chance to look good, and only retaliate later if that fails. And even if China did feel the need to retaliate, the audacity of what China is trying to do is well beyond a reasonable countermove.

What Is China Doing?

X (formerly Twitter)

SemiAnalysis (@SemiAnalysis_) on X

We see several main objectives behind this restriction, rather than a supply-chain cutoff:

⚆ Using the review process to obtain information on ad...

on the rare earth portion and does not think they are aiming at a widespread supply chain cutoff.

X (formerly Twitter)

Brad Setser (@Brad_Setser) on X

China -- per the excellent reporting on the WSJ/ @Lingling_Wei -- appears to be pursuing a strategy of applying maximum pressure in pursuit of maxi...

to try and get it all, as in full tariff rollback, rollback of export controls, even relaxation of national security reviews on Chinese investments. They’re laying many of their most powerful asymmetric cards on the table, perhaps most of them. That does seem like what is going on?

The export controls on chips presumably aren’t China’s primary goal here in any case. I assume they mostly want tariff relief, this is a reasonable thing to want, and on that we should be willing to negotiate. They get to play this card once before we (I hope) get our own production house in order on this, the card was losing power over time already, they played it, that’s that.

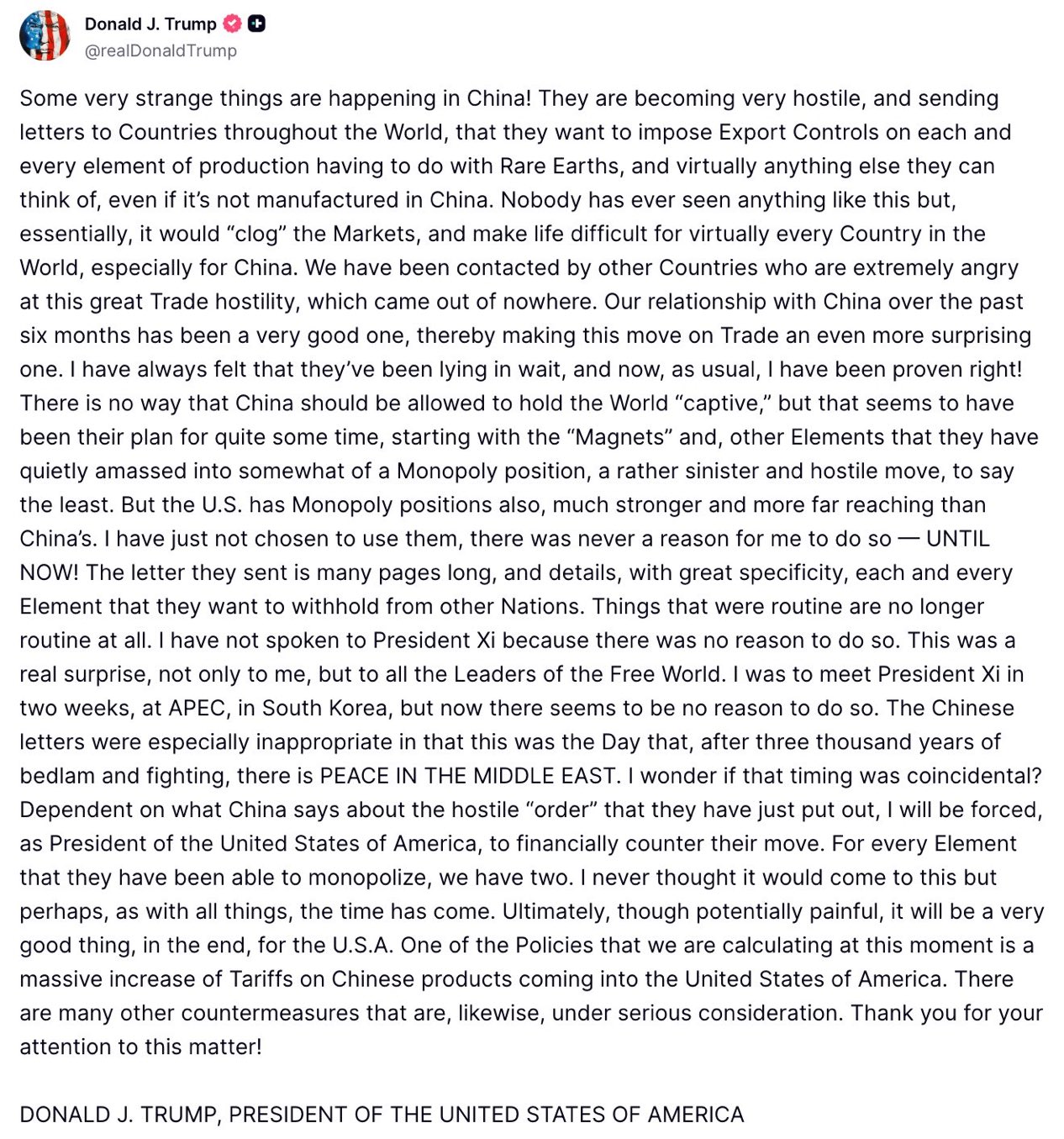

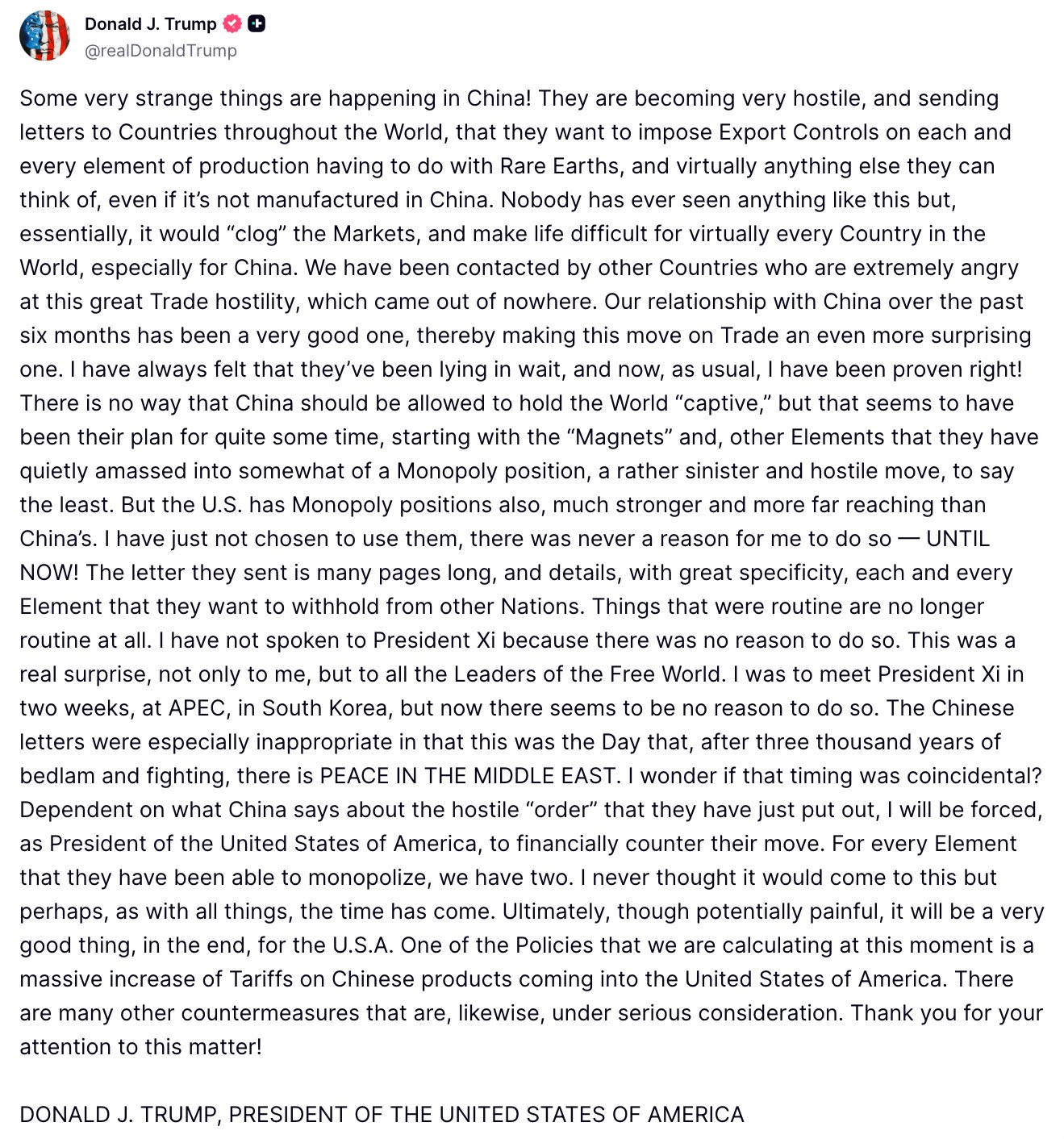

How Is America Responding?

X (formerly Twitter)

Rapid Response 47 (@RapidResponse47) on X

was to plan not to meet Xi at APAC and to threaten massive new tariffs, now that China is no longer ‘lying in wait’ after six months of what he claims were ‘good relations with China,’ hence the question we are now about to answer of what bad relations with China might look like, yikes. He says ‘things that were routine are no longer routine at all,’ which might be the best way to sum up the entire 2025 Trump experience.

X (formerly Twitter)

Vivek Sen (@Vivek4real_) on X

SOMEONE JUST OPENED A #BITCOIN SHORT 30 MINS BEFORE TRUMP'S TARIFF ANNOUNCEMENT AND JUST CLOSED WITH $88,000,000 PROFIT

HE OPENED THIS ACCOUNT TO...

, someone opened an account on that day, created a Bitcoin short and closed with $88 million in profit. It’s 2025, you can just trade things.

That threat was always going to be part of the initial reaction, and thus does not itself provide strong evidence that China overreached, although the exact degree of

was unpredictable, and this does seem to be on the upper end of plausible degrees of pissed.

The question is what happens next. China’s move effectively bets that China holds all the cards, and on TACO, that they can escalate to de-escalate and get concessions, and that Trump will fold and give them a ‘great deal.’

We are

X (formerly Twitter)

unusual_whales (@unusual_whales) on X

BREAKING: The Pentagon has launched a $1 billion buying spree to stockpile critical minerals, per Reuters

which we should have presumably done a long time ago given the ratio of the cost of a stockpile versus the strategic risk of being caught without, especially in an actual war.

We also are announcing this:

X (formerly Twitter)

First Squawk (@FirstSquawk) on X

BESSENT ON SUPPLY CHAINS, RARE EARTHS: GOING TO DO EQUIVALENT OF OPERATION WARP SPEED TO TACKLE PROCESSING

: BESSENT ON SUPPLY CHAINS, RARE EARTHS: GOING TO DO EQUIVALENT OF OPERATION WARP SPEED TO TACKLE PROCESSING.

I am excited to do the equivalent of by far the most successful government program of the past decade and Trump’s greatest success.

https://www.wsj.com/world/china/trump-tariffs-us-china-stock-market-e2652d66?mod=author_content_page_1_pos_1

), and both nations express privately they want to reduce tensions. No one actually wants a big trade war and both sides have escalated to de-escalate. So Trump is both making big threats and sending out the message that everything is fine. He’s repeating that America is prepared to retaliate if China doesn’t back down, and is going to demand full rescinding of the rare-earth export rule.

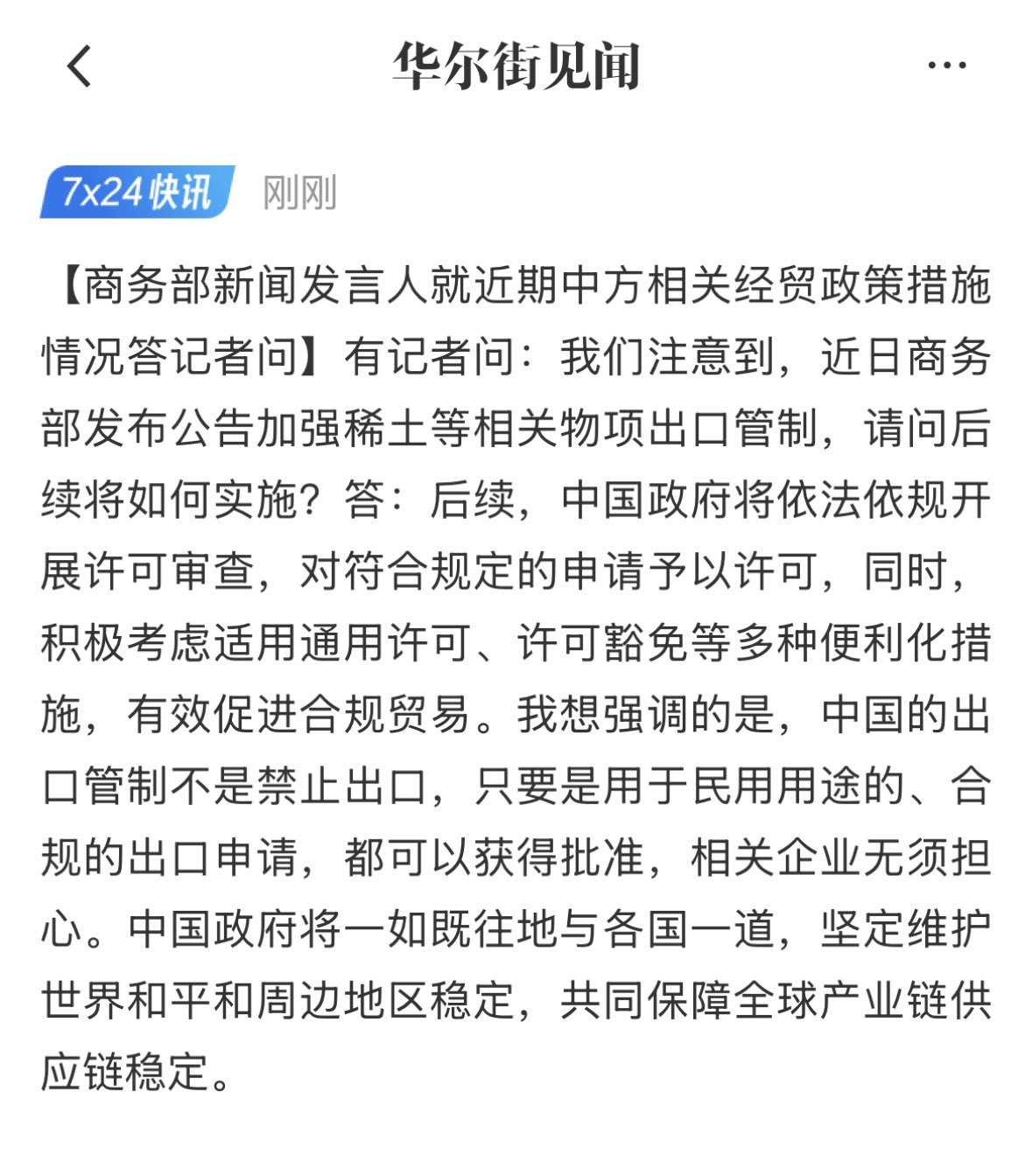

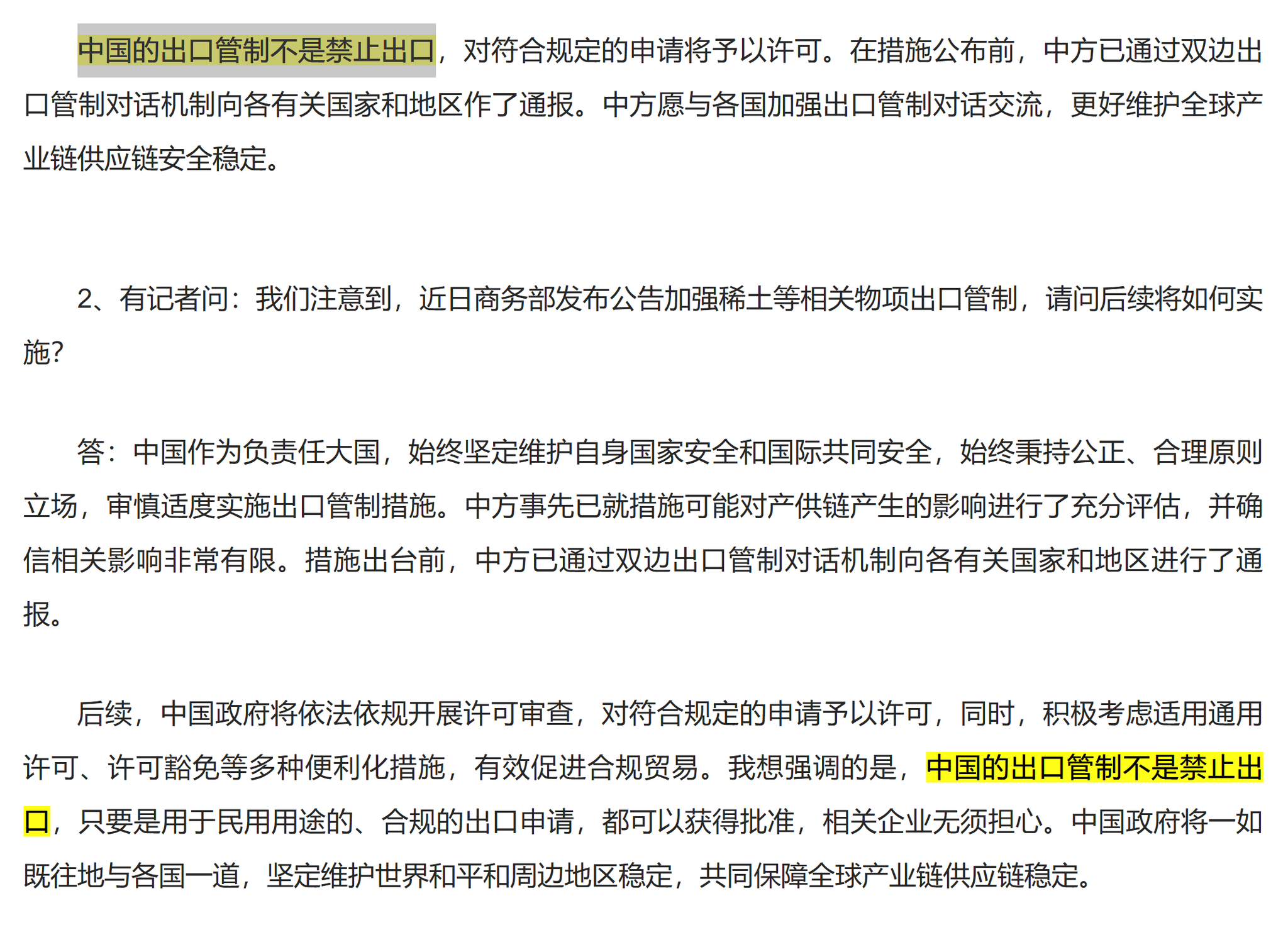

How Is China Responding To America’s Response?

China quickly

X (formerly Twitter)

Shanghai Macro Strategist (@ShanghaiMacro) on X

I sense Beijing’s restraint from this press conference Q&A.

Spokesperson of the Ministry of Commerce Answers Questions on China’s Recent ...

and indicate intention to de-escalate, saying that the ban is only for military purposes and civilian uses will be approved, all you have to do is get all the Chinese licenses, as in acknowledge Chinese extraterritorial jurisdiction and turn over lots of detail about what you’re doing, and hope they don’t alter the deal any further. No need to worry.

X (formerly Twitter)

Rush Doshi (@RushDoshi) on X

Recent PRC Ministry of Commerce public remarks are a must-read. Beijing seems a little rattled by the global response but is resolved to keep the r...

and worried about global reaction, and declining to respond to Trump’s threats yet, but resolved to keep their new rare earths regime.

Rush Doshi: Bottom Line: Trump wants this regime withdrawn. Beijing won’t do that, but is trying to reassure it won’t implement it punitively. Obviously, that is not a credible promise on Beijing’s part, and US and PRC positions are at odds.

Beijing is emphasizing that this is ‘not a ban’ except for military use. Thinking this is what needs to be emphasized indicates they misunderstand the dynamics involved. This was not something that was misunderstood.

What To Make Of China’s Attempted Reassurances?

Perhaps it was intended as a warning that they could have done a ban and chose not to? Except that implicit threat is exactly the most unacceptable aspect of all this.

The argument that others need not worry does not hold water. Any reasonable business would worry. As for governments, you can’t be permitted by others to remain the sole supplier of vital military supplies if you don’t let them go into others military equipment, even if the rules are only ever enforced as announced.

Nor is America going to let China demand unlimited information transfer about everything that touches their rare earths, or accept China having a legal veto point over the entire global supply chain even if they pledge to only use it for military applications.

As in, this is not merely ‘Trump wants this regime withdrawn.’ This is an unacceptable, dealbreaker-level escalation that America cannot reasonably accept.

So we are at an impasse that has to give way in some fashion, or this escalates again.

How Should We Respond From Here?

X (formerly Twitter)

Saif M. Khan (@KhanSaifM) on X

In response, the US government should not negotiate export controls; it should recommit to the PRC that export controls are non-negotiable national...

on our chip export controls, indeed given this move we should tighten them, especially on wagers and other manufacturing components.

We must use this as an impetus to finally pay the subsidies and give the waivers needed and do whatever else we need to do, in order to get rare earth production and refining in the West.

It’s not like all the deposits happen to be in China. America used to be the top producer and could be again. I strongly

X (formerly Twitter)

Dean W. Ball (@deanwball) on X

This is a very big deal. China has asserted sweeping control over the entire global semiconductor supply chain, putting export license requirements...

that we should (among other things) Declare Defense Production Act as needed on this one, as this is a key strategic vulnerability that we can and must fix quickly. As Dean points out, and economists always say, supply in the medium term is almost always more elastic than you think.

Note the justification China used for this new restriction, which is that any chip below 14nm or 256 layer memory has ‘military applications.’ Well then, where should we put the limit on our chip sales to them? They certainly have military applications.

X (formerly Twitter)

Rush Doshi (@RushDoshi) on X

President Trump pulls down APEC meeting in response to Chinese escalation.

It seems he is finally paying attention to the fact he is losing the tr...

, which would solidify this as a very serious escalation all around if it came to that. Presumably such an escalation is unlikely, but possible.

It Looks Like China Overplayed Its Hand

The way this is playing out now does update us towards China having miscalculated and overplayed their hand, potentially quite badly if they are unable to offer an acceptable compromise while saving face and dealing with internal pressures.

Asserting control over supply and terms of trade is a trick you hopefully can only pull once. Demonstrate you have the world over a barrel because no one else was willing to pay a modest price to secure alternative supplies, and everyone is going to go pay a modest price to secure alternative supplies, not only of this but of everything else too, and look hard at any potential choke points.

That dynamic is indeed also one of the big problems with Trump’s tariff shenanigans. If you prove yourself willing to use leverage and an unreliable trading partner (provoked, fairly or otherwise) then everyone is going to look to take away your leverage and stop depending on you. Hold up problems that get exploited get solved.

We Need To Mitigate China’s Leverage Across The Board

In this sense, the response must inevitably go well beyond rare earths, even if a deal is reached and both sides back down.

X (formerly Twitter)

Dean W. Ball (@deanwball) on X

We should not miss the fundamental point on rare earths: China has crafted a policy that gives it the power to forbid any country on Earth from par...

: We should not miss the fundamental point on rare earths: China has crafted a policy that gives it the power to forbid any country on Earth from participating in the modern economy.

They can do this because they diligently built industrial capacity no one else had the fortitude to build. They were willing to tolerate costs—financial and environmental and otherwise—to do it.

Now the rest of the world must do the same.

China has created an opportunity of tremendous proportions for all countries that care about controlling their destiny: the opportunity to rebuild.

Every non-Chinese infrastructure investment, sovereign wealth, and public pension fund; every corporation that depends on rare earths; and every government can play a role.

This is an opportunity not just for the US, but for every country on Earth that wants to control its destiny. Together, we can build a new supply chain designed to withstand unilateral weaponization by a single country—one spread throughout the world.

Always remember that supply is elastic. If our lives depend on it, we can surmount many challenges far faster than the policy planners in Beijing, Brussels, and Washington realize.

China and Rare Earth Metals, Chips and Rare Earths, The U.S.’s Self-Inflicted Challenge – Stratechery by Ben Thompson

, that America gave the rare earth mining industry away by letting the Nuclear Regulatory Commission classify waste as nuclear, thus skyrocketing costs (so a fully pointless self-own, the same as on nuclear power) followed by letting the Chinese buy out what was left of our operations. We could absolutely get back in this game quickly if we decided we wanted to do that.

X (formerly Twitter)

Peter Harrell (@petereharrell) on X

This question--why can't we just solve our rare earths problem already!--comes up a lot. As someone who worked on this when I was in government, se...

going is hard. Permitting and lawsuits make mining in America difficult (read: borderline impossible), it’s hard to get politics going for things that don’t come online for years, and profitability is rough without purchase and price guarantees.

That is very hard under our current equilibria, but is eminently solvable given political will. You can overcome the permitting. You can pass reforms that bypass or greatly mitigate the lawsuits. You can use advance market commitments to lock in profitability. The strategic value greatly exceeds the associated costs. If you care enough.

What About The Chip Export Controls?

What about the parallel with advanced AI chips themselves, you ask? Isn’t that the same thing in reverse? There are some similarities, but no. That is aimed squarely at only a few geopolitical rivals, contained to one particular technology that happens to be the most advanced and difficult to duplicate on Earth, and one that China is already going full speed ahead to get domestically, and where share of global chip supply is a key determinant of the future.

Yes, there are elements of ‘China doesn’t get to do extraterritorial controls on strategic resources, only America gets to do extraterritorial controls on strategic resources.’ And indeed, to an extent that is exactly our position, and it isn’t new, and it’s not the kind of thing you give up in such a spot.

This May Be A Sign Of Weakness

We also should consider the possibility that

Foreign Policy

China’s Tech Obsession Is Weighing Down Its Economy

A decade of cutting-edge investment hasn’t translated into growth.

and they could feel backed into various corners, including internal pressures. Authoritarian states with central planning can often do impressive looking things, such as China going on history’s largest real estate building binge or its focus on hypercompetitive manufacturing and technology sectors, hiding the ways it is unsustainable or wasteful for quite a long time.

China has a huge slow moving demographic problem and youth that are by all reports struggling, which is both a crisis and indicates that many things are deeply wrong, mounting debt and a large collapsed real estate sector.

Recently China started clamping down on ‘negative emotional contagion’ on social media.

https://marginalrevolution.com/marginalrevolution/2025/10/china-understands-negative-emotional-contagion.html

but I would instead suggest the primary thing to observe is that this is not what you do when things are going well. It only makes the vibe more creepily dystopian and forces everyone’s maps to diverge even more from reality. It reflects and creates increasing tail risk.

What Next?

I would presume the default outcome is that a detente of some form is reached before massive escalations actually get implemented. The market is concerned but not freaking out, and this seems correct.

There is still a lot of risk in the room. When cards like this are put on the table, even with relatively conservative negotiation styles, they sometimes get played, and there could end up being a fundamental incompatibility, internal pressures and issues of loss of face here that when combined leave no ZOPA (zone of possible agreement), or don’t open up one without more market turbulence first. I would not relax.

Is there risk that America could fold here and give up things it would be highly unwise to give up? Not zero, and when powerful cards like this get played it is typical that one must make concessions somewhere, but I expect us to be able to limit this to places where compromise is acceptable, such as tariffs, where our position was always in large part a negotiating tactic. If anything, this move by China only emphasizes the importance of not compromising on key strategic assets like AI chips, and tightening our grip especially on the manufacturing equipment and component sides.

Even if we end up making substantial concessions on tariffs and other negotiable fronts, in places China sensibly finds valuable, this whole exchange will still be a win. This was a powerful card, it is much harder to play it again, and we are going to make much stronger efforts than before to shore up this and other strategic weaknesses. If this causes us to take a variety of similar vulnerabilities properly seriously, we will have come out far ahead. While in general, I strongly dislike industrial policy, inputs that create holdup problems and other narrow but vital strategic resources can provide a clear exception. We should still strive to let markets handle it, with our main goal being to pay providers sufficiently and to remove restrictions on production.

https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/rTP5oZ3CDJR429Dw7/trade-escalation-supply-chain-vulnerabilities-and-rare-earth#comments

https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/rTP5oZ3CDJR429Dw7/trade-escalation-supply-chain-vulnerabilities-and-rare-earth https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/XicHwcXewsBTnWLwG/gnashing-of-teeth

https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/XicHwcXewsBTnWLwG/gnashing-of-teeth https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/XicHwcXewsBTnWLwG/gnashing-of-teeth

https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/XicHwcXewsBTnWLwG/gnashing-of-teeth