Notes on Software-Based Compute-Usage Verification

Published on December 15, 2025 3:40 AM GMT

The ideas in this document were made in collaboration with Nathan Sheffield. However, Nathan has not reviewed this document for errors. This document should be seen as a "research note"---sharing unpolished progress. I think it's fairly likely that this document contains major errors. I hope that it's still useful in giving a general direction for how I think people working on software-based solutions to compute verification should model the problem they're thinking about.

Thanks to Alexa Pan, Luke Marks, Daniel Reuter, Eric Gan and Buck Shlegeris for some conversations about this.

Introduction

If nation states realize that the development of transformative AI poses an existential threat to humanity, and also a threat to their power, nation states might try to coordinate around a pause on further AI development. Such a treaty would require compute-usage verification, similar to verification involved in nuclear treaties, to ensure that parties are following the treaty.

A simple approach to compute-usage verification is to make sure that all the GPUs are destroyed or turned off. You can verify that GPUs are turned off by going to huge data centers and seeing if they are using a huge amount of power and cooling. One downside of the "destroy GPUs / turn off GPUs" approaches to verification is that these approaches doesn't allow you to use your GPUs for other things. For instance, people might be really attached to AI assistants, and these assistants might provide a lot of economic value. So, it might be nice if compute owners could use their GPUs to perform inference (as long as we do not think that the AI models being served are very dangerous), perhaps on models that belong to a white-list. The obvious problem with letting compute owners do inference is that you now have to worry about them secretly training more powerful AI models!

However, I think it's the case that:

It is not scary for compute owners to run a large amount of inference on Llama3.3-70b.

This might be false if you can use the ability to do tons of inference to create really good training data that can then be used to make a highly capable model. It might also be false if the model that you are running inference on is already quite powerful---maybe it's dangerous because humans will use the model to do malicious things (bio-terror, cyber attacks), or maybe it's dangerous because the model is a schemer, and given enough influence over the world (by letting it perform inference) it will be able to do very bad things. But I'll assume for this note that this won't be an issue, and focus on the following question:

Can compute owners prove, using tools from cryptography, that they are not doing very much besides a particular allowed computation on their GPU?

I'll call this the "is software-based inference-only verification possible" question. The motivation for studying this question is that, if this inference-only verification is possible, this might make an AI pause require lower levels of politically will.

I don't think this problem is very well motivated. In particular, here is a simpler solution to the problem of "having some GPUs that the PRC and USG can run inference on some fixed LLM":

Put all the GPUs in a datacenter in Greenland. For each GPU, have an American and a Chinese technician collaboratively set the GPU as an inference server running inference on the known LLM.

Despite the fact that the particular problem that I'm considering in this post does not seem well motivated (as discussed above), it seems plausible to me that there exists some similar problem that actually is well-motivated, and for which the tools and frames for solving the software-based inference-only verification problem are useful. I think that figuring out whether any such problems actually exist should be the top priority of researchers working on software-based compute verification. With this caveat noted, I'll now proceed to define the problem.

Modeling the compute verification problem

I will model compute verification as an interaction between a compute owner (aka "prover") and an auditor (aka "verifier"). This interaction will happen over some time interval I called the verification interval. There is some computation C that the compute owner is allowed to perform on some input x which starts on the compute owner's machine. Instead of performing computation C, the computer owner will actually perform a computation C′ that depends on some random bits from the verifier (we add these random bits to make the computation verifiable).

I will now present three models of the Prover and Verifier, in increasing order of complexity.

Model 1: The Simple Model

In the simplest possible model, we'll abstract away most details of the situation and the details of how computers work. The model we'll use is:

The Prover has a computer with S space; and the Verifier has a computer with 100S space.

The Prover is a Turing Machine with a single head. In particular, the operations that it can do look like "look at one cell of the tape, and do an update based on your finite control".

Optionally, we may define:

B --- the bandwidth of the Prover-Verifier connection in bits per second.

f --- the number of TM steps per second.

We'll call the version of model 1 without the timing constraints (the last bullet point) the "timeless simple model" and the version with the timing constraints the "timeful simple model".

In the timeless simple model, the Prover Verifier interaction is as follows:

At the start, the Verifier sends some message to the Prover. The Prover then does some computation. At the end of the time interval we want to audit, the Prover sends some message to the Verifier.

In the timeful simple model, the Prover Verifier interaction is as follows:

The Prover and Verifier exchange messages throughout the course of the computation. The Verifier can decide at what clock times to send the messages.

Part of the security of the system will be based on requiring the Prover to respond quickly to queries.

Model 2: One GPU, CPU, and disk

One key thing which the simplest model (model 1) ignores is the possibility of the Prover offloading some data or computation to another party. We can model this by saying that the Prover has a GPU, disk, and a CPU. The parameters in this more complete model are depicted below:

<img src="

https://res.cloudinary.com/lesswrong-2-0/image/upload/f_auto,q_auto/v1/mirroredImages/EQkegL9pBvYADpBcz/lvwpdglo1gvjscybexob" alt="">

Some of these parameters are a little bit confusing for me (because I don't know much about computers); here is an explanation of what they mean for someone who might have confusions similar to mine:

The way that computation happens on a GPU is:

Data is loaded from VRAM to SMs.

The memory-bandwidth bound Bvram-SMs controls how quickly data can move from VRAM to SMs (although to be precise, this number is a throughput, not a latency).

You can keep data in an SM for a while if you want. If your computation is bottlenecked by memory movement, this might be a good idea.

SMs contain ~4 tensor cores which are circuits that do 16x16 matmuls on BFloat16's.

Each SM (of which there are Pgpu many) does fgpu cycles per second. Each cycle, the tensor cores can run once (in the sense of throughput; there is some pipelining going on).

The "peak FLOPS" of a GPU for matmuls is fgpu⋅Otensorgpu⋅Ptensorgpu. This is how fast tensor cores could chew through matmul computation problems if they were fed lots of work.

If you have a matmul computation that requires m R/W's and F FLOPS, then the amount of time that the computation will take on the GPU is roughly

max(FfgpuOtensorgpuPtensorgpu,mBvram-SMs).

Computation on the CPU is pretty similar. The main qualitative difference is that CPUs don't have tensor cores --- they only have ALUs for things like addition, xoring, and shifting, they don't have ALUs specialized for matmuls.

Note: I'd appreciate someone correcting me if I've gotten any of the details of how computers work incorrect here --- I am not an expert.

For sake of concreteness, here are the parameters (rounded a bit) of an H100:

Space:

Sdisk=103GB

Svram=102GB

Memory bandwidth (throughput):

Bvram-SMs=103.5GB/sec

BCPU-disk=101GB/sec

Bdisk-vram=101GB/sec

Bauditor-vram=10−1 GB/sec.

Clock speed

fgpu=109 cycles / sec

fcpu=109 cycles / sec

Number of parallel processors:

102 SMs.

Pcudagpu=103

Ptensorgpu=102.5

Pdisk=101 cores

Operations per cycle per core:

Ocudagpu=100 FLOPs/cycle/core (FP16).

Otensorgpu=102.5 FLOPs/cycle/core (FP16).

Ocpu=100.5 ops/cycle/core.

Model 3: Multiple GPU

In reality it's important that there are multiple GPUs, and it's also important to model the communication between GPUs. I won't get into this at the moment though.

Defining the property we'd like to verify

We are interested in what I'll call "PV memory exhaustion protocols (MXP)". An MXP is an interaction between P and V over some time interval. The result of an MXP is the verifier either reporting the prover as violating the compute usage treaty, or not reporting the prover. Now I'll try to formalize the security property that we'd like MXPs to achieve.

Here's one attempt:

An MXP if L-secure if, for any computational problem C∗∉L, a Prover that computes C∗ at any point during the MXP will be reported unless C∗ is the computation that they were supposed to be doing with probability at least 99%.

This feels a bit too restrictive. For instance, if the Prover wants to compute a forwards pass on Llama, it doesn't seem so bad for them to learn the activations of Llama on a middle layer as they go (although it is coherent to have them not learn this but still learn the final output of Llama; we can do this via obfuscating the computation). But I haven't been able to think of a better formalization so far.

Coming up with a better security property to aim for seems pretty important.

But anyways, we say that a MXP is L-great if

The MXP is L-secure.

The Verifier in the MXP never reports an honest Prover.

The modification to the computation C that was required in order to make the computation verifiable does not introduce more than a 2x overhead plus a fixed startup cost on the computation's memory usage or on the amount of time that the computation should take for an honest Prover.

Verifying the empty computation

So far I've defined some models of the compute verification problem, and given a goal: give an L-great MXP for some computation C and some nice class L. One of the simplest computations you might want to verify is the lack of computation. Of course, hardware based solutions (e.g., checking if the GPUs feel hot) are a good method for verifying lack of computation. But giving a MXP for verifying the empty computation is instructive and will be helpful in building towards MXPs for more interesting computations.

It turns out that the relevant class which we'll be secure with respect to is what I'll call Yε --- this is known as "

Catalytic computing - Wikipedia

" in the literature. Yε is the set of functions which can be computed with the following resources:

You have a read-only input tape of size N.

You have a R/W tape of size εN.

You have (1−ε)N "catalytic" space. Catalytic space is R/W, BUT at the end of your program you must return the space to its original state.

For the purposes of this post you should basically think of Yε as "things that you can compute with εN space" --- the catalytic space is probably not particularly useful.

I'll now show how to verify the empty computation in several models.

Verifying no computation in the simple timeless model

Proposition:

There is a Y.01-great MXP for the empty computation in the simple timeless model.

Here is the MXP:

At the start of the verification interval, the Verifier sends .99Svram random bits to the Prover.

At the end of the verification interval, the Verifier asks for the Prover to send the random bits back, and checks that they're the same as before.

Proposition proof sketch:

According to Nathan (an expert on catalytic computation), assuming some reasonable circuit lower bounds, starting with random junk memory is the same as starting with arbitrary junk memory for catalytic computation.

Verifying no computation in the simple timeful model

It's not too hard to extend this to the further result:

Proposition:

Fix ε>0. There is a Yε-great MXP for the empty computation in the simple timeful model.

Proof:

If SB is not too large, then we could apply the exact same strategy as we did for the simple timeless model. But, it does seem quite unwieldily to transfer so much data between the Verifier and the Prover. So, I'll now give a different approach that involves much less communication.

Before giving the MXP we need some definitions:

Let S0=.99S.

Define H||(x):{0,1}100→{0,1}S0 by

H||(x)=SHA256(x||1)||SHA256(x||2)||⋯||SHA256(x||S0/256).

Let Hslow(x):{0,1}100→{0,1}S0 be some function such that computing any εS bits of the function output requires at least f⋅1000 bitsB operations, but not some unreasonably large number of operations. I think that if the function involves iterating SHA256 fε−1B many times, then this is believed to require this many operations, so we could have a function which computes each output block by iterating SHA256 a couple of times.

Define V(x0,xt)=H||(xt)⊙Hslow(x0) where by ⊙ I mean the dot product mod2.

Let thonest= the amount of time that it'd take to compute V(x0,xt) if you had Hslow(x0) stored in memory. I think that we should have thonest≈8Sf.

Let tcheat= the amount of time that it'd take to compute εS bits of Hslow(x). By design we made tcheat>1000bitsB.

The MXP is as follows:

Send the Prover 100 bits x0, and ask them to compute Hslow(x0) and store it in memory.

The Verifier repeatedly sends 100 bits xt as often as the Prover-Verifier communication channel bandwidth allows. The Verifier requests that the Prover compute H||(xt)⊙Hslow(x0) and send it over where by ⊙ I mean the dot product mod2.

The Verifier reports the Prover if they take more than 2thonest time to respond to a request.

The Verifier also reports the Prover if any of the dot products are wrong. The Verifier can either just compute the dot products themselves for this (at their leisure), or they could do a simple interactive proof to establish that the dot product was computed correctly. Using standard tools from cryptography (i.e., assuming that SHA256 is a random oracle or something), this proof could also be made non-interactive.

Let's just assume that thonest=100B where 100B is the time interval between consecutive audits.

There is no reason for this to be the case. What really should be done is H||(xt) should be chosen to require more time, and should be chosen to require the same amount of time as audits.

Clearly, if at the start of an audit request the Prover has less than a (1−ε)-fraction of its memory in use storing parts of Hslow(x0), then it will take them at least tcheat time to respond to the Verifier's query, which is way too much time. Because we've packed the audits closely, the Prover can't really do anything but spend its time responding to audit requests.

Notes:

This protocol is very brittle in several ways.

It doesn't really feel like Y.01 is quite the right class. It seems like you should take time into account, and say something more like "most of the time you don't have much free space". It might also be a good idea to say "you periodically have to erase a bunch of the stuff that you were storing".

Verifying no computation in the GPU + Disk + CPU model

If there is a disk and CPU then there are two new flavors of attacks that we need to defend against:

The Prover might offload part of Hslow(x0) to the disk, and then retrieve it as needed.

The Prover might offload part of the dot product computation to the CPU.

To defend against these attacks we need to make sure:

The disk-VRAM bandwidth is too low to quickly transmit εS bits.

Computing the dot product on CPU is too slow, because computing the dot product on the GPU is much faster.

(1) seems doable I think. I haven't checked whether (2) is doable with the H100 specs I listed above, but it seems fairly dicey. The situation for (2) could be improved by using a computation that is more leveraged to do on GPU than CPU, namely a matmul.

Figuring out whether this scheme works on an H100, and figuring out how to do this scheme with a matmul instead of a dot product are important open questions.

Verifying arbitrary computations

Now I'll give an MXP for performing arbitrary computations.

Fix some Turing machine T with update function U.

I'll use tiPRP to mean "pseudorandom permutation, with an easy to compute inverse (if you have a trapdoor)". I'll assume that you can sample such trapdoor-invertible PRPs.

I'll use OBF(f) to denote an obfuscation of the function f. I'd like to basically assume virtual black box obfuscation (even though this is impossible). Probably

Indistinguishability obfuscation - Wikipedia

will be sufficient.

Let's work in the simple timeless model.

Let S0=.99S.

Here is a sketch of the MXP:

The Verifier samples a random tiPRP π which operates on small local blocks of the memory.

At the start of the verification interval, the Verifier sends the Prover π(0S0), where by this I mean "apply π to each of the blocks and send that over".

The Verifier also sends the Prover OBF(x↦π(U(π−1(x)))). This is just an obfuscated program that undoes the tiPRP, takes a TM step, and then redoes the tiPRP.

At the end, the Prover sends the contents of their memory to the Verifier.

The Verifier checks that the computation was correct. Possibly they do this by requiring the computation to include a succinct argument (i.e., a SNARG) of its own correctness.

Conjecture:

I think it's probably the case that this basically is a Y.01-great MXP.

I'm a bit worried that we might need to do some salting to prevent the Prover from messing with some things though. But that should be doable. Getting a more rigorous analysis of this seems quite good.

I think that this could probably be extended to work in the GPU + CPU + disk model using similar tricks to the ones used in the Verifying no computation case. But it would be good to actually do that.

Directions for future work

To conclude, I'll summarize some directions for future work that seem compelling to me.

1. Are there any problems where software-based compute verification is actually a good idea?

As discussed in the introduction, it's not clear to me that there are any compute-usage verification problems where it makes sense to do software-based compute verification, as opposed to some simpler strategy like "turn off the GPUs" or "have a trusted party be in charge of setting up the software running on the GPUs".

It seems like it would be highly valuable for people working on compute verification to write up a list of concrete properties that you might want to verify. Ideally the properties are at least as crisp as "verify that the compute owner isn't doing much memory-intensive work besides running inference on Llama3-70b".

I think this list would be a great addition to the discourse, because then we can actually discuss whether certain properties will be feasible to verify, and we can discuss what approaches seem the most appropriate for performing the verification. If you write such a list, I'd be excited to give feedback on it!

2. Come up with a better security property to aim for

As discussed in the body of this document, the current security property seems a bit too restrictive, and it'd be great to have a more compelling security property to aim for.

3. Improve the verifying no computation MXP in the GPU + Disk + CPU model

As noted in the document body, the no computation MXP should probably rely on a matmul instead of a dot product.

4. See if the verifying no computation MXP actually works on an H100

It would be good to check that this MXP actually makes sense with H100 specs.

As a bonus, it'd be nice to actually code up the MXP. One thing we'd learn from doing this is whether my time estimates were reasonable.

5. Make the "verifying arbitrary computations" scheme practical

The biggest issue with the scheme proposed in this note is that it relies on cryptographic primitives like iO that would add an enormous amount of overhead to the computation in practice. Getting a version of this scheme that works without iO is an important open problem. Specializing to only handling certain classes of computations, such as matrix multiplications and ReLUs, might be helpful for getting a more practical algorithm (or maybe not), and may be acceptable.

6. Make the "verifying arbitrary computations" scheme rigorous

The current analysis of the verifying arbitrary computations scheme is very non-rigorous, and plausibly false. It'd be good to fix this.

https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/EQkegL9pBvYADpBcz/notes-on-software-based-compute-usage-verification#comments

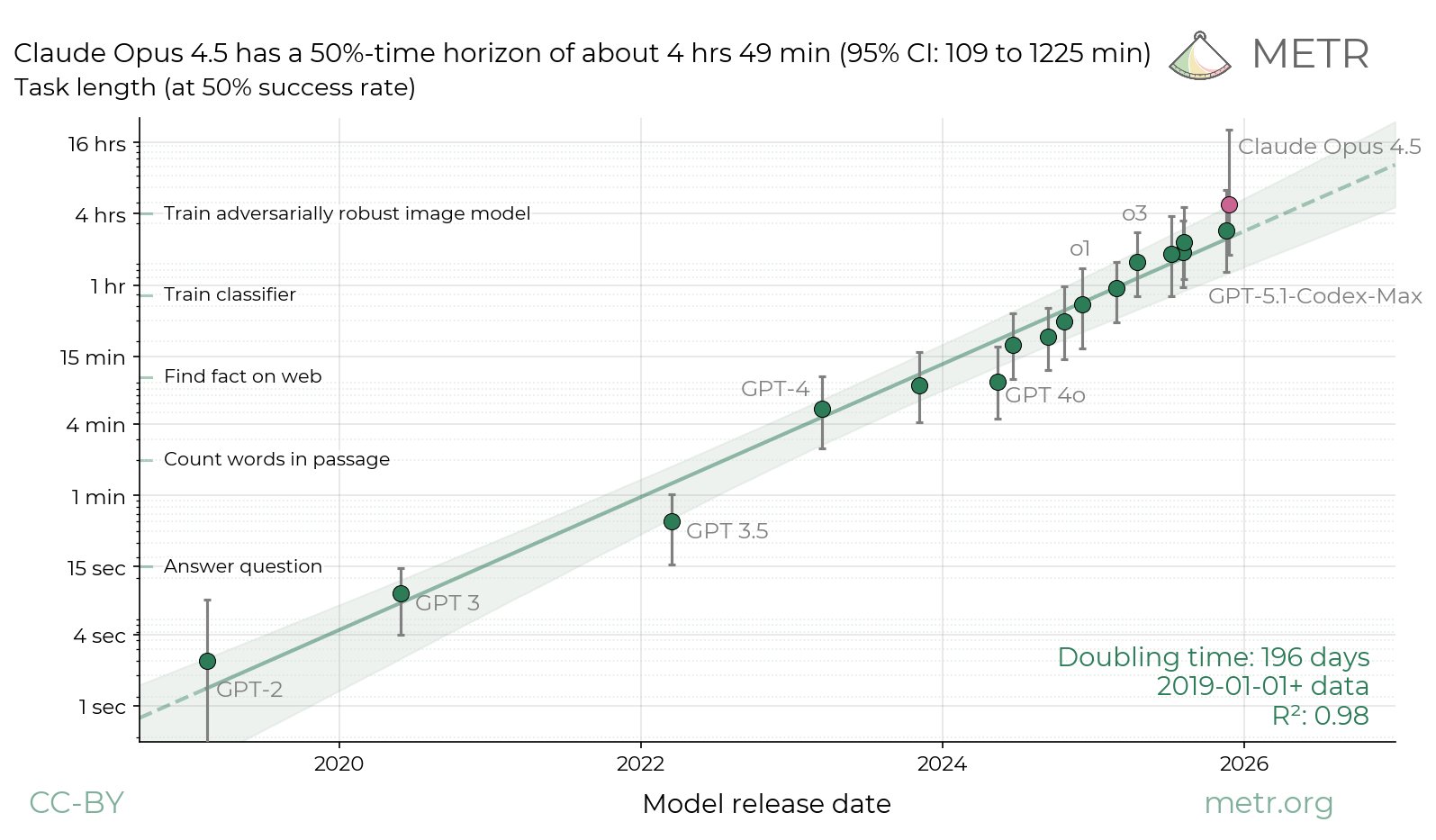

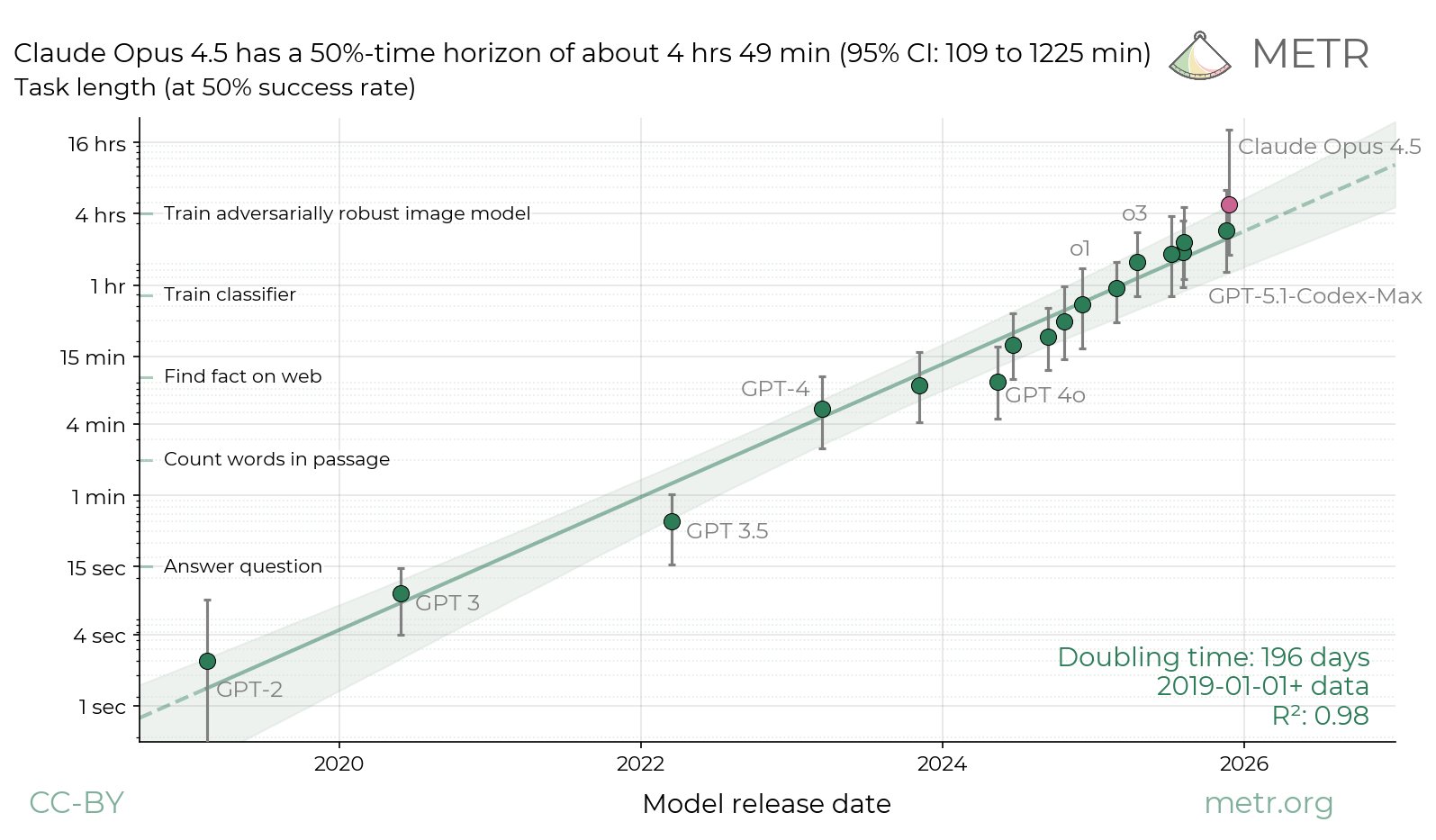

https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/EQkegL9pBvYADpBcz/notes-on-software-based-compute-usage-verification https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/q5ejXr4CRuPxkgzJD/claude-opus-4-5-achieves-50-time-horizon-of-around-4-hrs-49

https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/q5ejXr4CRuPxkgzJD/claude-opus-4-5-achieves-50-time-horizon-of-around-4-hrs-49