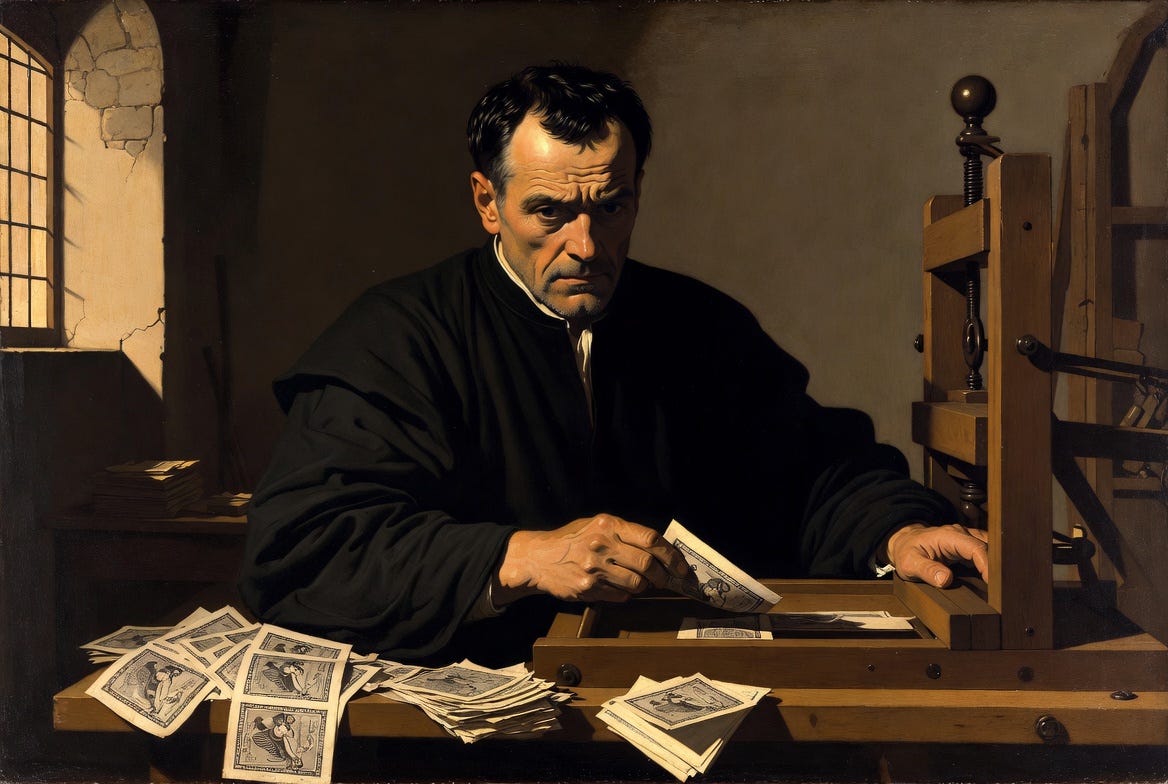

Counterfeiters are found in the eighth Circle of Hell, according to the 14th-Century poet Dante.

In Dante’s Inferno, the first part of his epic poem The Divine Comedy, he guides readers through the nine circles of Hell, cataloging sinners and their eternal punishments. Deeper circles of Hell punish progressively worse sins. In the eighth circle, Dante encounters Master Adam, a counterfeiter condemned to unquenchable thirst and a grotesquely bloated body.

Master Adam was based on a real life person, Adam of Brescia, who was burned alive at the stake in 1281 for counterfeiting Florence’s gold florins. His crime: producing 21-carat coins instead of the full purity 24-carat coins. Dante placed him deep in Hell’s architecture, notably deeper than thieves and the violent.

Counterfeiting money has been, and continues to be, universally recognized as wrong. In Dante’s time, the punishment reflected the severity of the sin: death by fire in this world and eternal damnation in the next.

What Exactly Was Adam’s Sin?

Consider the method: Master Adam might have melted 100 pure gold florins, mixed the gold with another metal, and re-minted 115 “fake” florins. Each coin appeared genuine, with the same weight, size, stamp, and luster, but contained only 21 carats instead of 24.

Upon spending a counterfeit coin, say at a shoemaker, Master Adam would break two commandments in a single transaction: thou shalt not lie and thou shalt not steal. The lie is representing the coin as full purity when it’s actually diluted, and the theft is taking three carats of gold more in value than what he’s giving.

The shoemaker, unaware he holds a counterfeit, spends it at the baker. The baker spends it at the tailor. The tailor pays the builder. Only when the coin’s purity is tested does the fraud emerge. The final holder, in this case the builder, realizes his loss. Unless the coin’s origin can be traced back to the counterfeiter, the theft cannot be remedied. Master Adam’s theft is ultimately manifest with coin’s final holder.

But what if the counterfeit coin is never discovered?

If no individual can identify a specific loss, is it still theft? If so, who was robbed and how much?

The Perfect Counterfeiter

With gold coins, fraud can be detected since purity can be tested. But imagine Master Adam had lived in our era of fiat currency, with paper money disconnected from gold-backing. And, suppose he could produce paper florins perfectly indistinguishable from genuine currency: identical paper, ink, design, and serial numbers.

If no test could distinguish real from fake, these counterfeits would circulate forever. No one suffers an identifiable theft. No one catches a verifiable lie. The “fake” money functions identically to “real” money.

Would producing these perfect counterfeits still be lying and stealing?

To understand the answer, consider what makes gold coins legitimate. In a gold system, supply constraint is natural. The only way to obtain a gold coin is by mining gold yourself or trading your productive labor with someone who did, constraining the supply of gold. A gold coin is a physical manifestation of invested time and effort. When Master Adam diluted his coins from 24 carats to 21, he was lying about having done the requisite work and stealing the value of that three-carat difference.

But in a fiat money system, where money isn’t backed by gold or any commodity, it’s no longer a manifestation of work performed. Someone simply printed it. The natural constraint on the money supply disappears.

This is where perfect counterfeiting and money printing become synonymous. Both create money without productive work. Both exchange that money for real goods and services. When counterfeiting becomes perfect, when fake is indistinguishable from real, the moral crime shifts from deception to dilution, with the only difference being legal authority.

Consider what happens when Master Adam scales his operation with paper florins. If he prints one note and buys a pair of shoes, the impact is negligible. But what if he prints a hundred thousand notes? If it costs him one florin to produce 100 florins’ worth of notes, he gains 99 florins profit per note.

As he floods Florence with these perfect counterfeits, more money chases the same goods. Prices rise. More florins per loaf of bread, per pair of shoes, per house. When money supply increases, each unit buys less. Supply and demand applies to money itself.

Master Adam buys land, buildings, and businesses. He acquires real wealth without contributing real work. Meanwhile, every florin holder becomes poorer as their purchasing power diminishes. At smaller scales it’s hard to see, but at larger scales, the theft is obvious. He’s causing inflation through money printing. He gains at the expense of the community.

Master Adam’s paper florins are claims on others’ productive work—the shoemaker’s labor, the farmer’s harvest, the builder’s skill—without corresponding work of his own. It’s theft, distributed so broadly across all money holders that each individual loss seems impossible to measure.

Even without an identifiable victim suffering a measurable loss, the theft is real. It’s stealing from everyone who holds that money by diluting its value.

First Comes Privilege

Counterfeiting doesn’t hurt everyone equally. The pattern of harm depends entirely on proximity to the new money, specifically who receives it first and who receives it last.

When Master Adam first spends his counterfeit florins, prices haven’t adjusted yet. He buys houses at prevailing market rates, acquiring real assets at real prices with worthless paper. Those who sold to him now have extra florins to spend.

These sellers spend in the economy, buying other houses and goods at prices that haven’t fully adjusted to the expanded money supply. The net buying pressure bids up prices, particularly for scarce or supply-constrained goods (real estate, businesses, precious metals, etc…), since new supply can’t be readily produced to meet an influx of demand.

As counterfeit money cascades through the economy, each subsequent recipient finds more prices already bid up. Scarce assets have risen fastest, while common goods have risen slower. By the time the expanded money supply reaches its final recipients, months or years later, prices for everything have climbed. The last person to receive the money encounters an economy where prices are elevated everywhere.

This is known as the Cantillon effect, named for economist Richard Cantillon. Those closest to new money’s source benefit most, purchasing at old prices with new money. Those furthest suffer most, earning money that buys progressively less.

Additionally, the entry point of money creation determines winners and losers. The moment Master Adam’s counterfeit money enters the economy, they transfer value based on their path. If he buys land first, landowners benefit. If he buys government bonds first, bondholders benefit. If he pays wages directly, laborers benefit… until prices catch up.

The question isn’t whether counterfeiting steals, but from whom and in what order.

Savers and Earners vs. Assets and Debt

Beyond proximity to the money printer lies another dimension of theft. Even among people who are equally distant from new money creation, some are systematically plundered while others benefit.

-

The Saver: A laborer whose wages are set at the beginning of the year loses purchasing power progressively as Master Adam’s counterfeiting drives prices throughout the year.

-

The Earner: A merchant who saved 100 florins to buy land discovers that land now costs 110 florins. His nominal wealth is unchanged, but his real purchasing power has declined.

-

The Asset Owner: A nobleman who owns land and buildings sees these assets appreciate in price. He produces nothing, works not at all, yet his wealth measured in florins increases faster than common goods and services.

-

The Debtor: An investor who borrowed 100 florins at fixed interest now owes the same nominal amount, but his debts are less of a burden. He uses the borrowed funds to buy scarce assets, so his debt shrinks in real terms while his assets appreciate.

What this means is an expanding money supply hurts savers and earners, while benefiting asset owners and debtors.

The poor suffer most because they depend disproportionately on cash savings and earnings. The wealthy benefit most because they own assets and access credit at large scales. The wealthy can also borrow against appreciating assets to buy more assets, which rise in price, enabling more borrowing and creating a compounding advantage.

An unconstrained money supply rewires incentives across the economy. Saving becomes less rational as purchasing power erodes. Wage-earning loses its benefits when earnings buy less by the time they are received. Debt-taking turns profitable when it can be repaid with debased currency. Scarce asset accumulation, especially through debt financing, becomes the best pursuit.

Counterfeiting is not merely lying and stealing. It’s something far worse.

The Decivilizing Force

When money increasingly loses value, it changes society. People minimize savings, accelerate consumption, embrace debt, chase assets, and gravitate toward sources of new money creation rather than toward productive activity and honest work.

Civilization depends on the opposite structure. Nations are built by producing more than is consumed and saving the surplus for the future. Cathedrals, universities, workshops, and scientific inventions all require delayed gratification and stored productivity. The future is financed by restraint in the present to have more in the future.

Master Adam’s counterfeiting punishes these civilizing activities at the margin. The productive worker keeps a bit less of what he earns. The saver retains a bit less of his stored labor. Meanwhile, everyone takes incremental steps toward speculation or debt.

Wealth inequality widens because those with capital adapt fastest. The wealthy already hold appreciating assets, access cheap credit at scale, and can leverage existing holdings to acquire more. Those without capital, who must first earn and save before they can invest, fall further behind as wages and savings lose value. Monetary expansion systematically amplifies this gap.

Most countries have progressive taxation, meaning the wealthier you are, the more you pay. Monetary expansion does the opposite. It’s regressive, meaning the poorer you are, the more you suffer. Unlike Robin Hood, who took from the rich to give to the poor, money printing more closely resembles the Sheriff of Nottingham, taking from the poor to give to the rich.

Over time, the economy reshapes itself around these incentives. Prudence gives way to risk-taking, work to speculation, and saving to leverage. Behaviors are warped, society changes.

This is why counterfeiting is destructive beyond the act of theft itself. It falsifies price signals, amplifies the Cantillon effect, expands the wealth gap and severs the link between productive contribution and prosperity. As it scales, it does not merely redistribute wealth, it erodes the civilizational mechanisms that enables societies to prosper.

From Medieval Florence to Modern Central Banks

Florence burned Master Adam at the stake because counterfeiting goes beyond theft. The severity of the punishment reflected the severity of the crime: one man benefiting by imposing hidden, decivilizing costs on the entire community.

Now ask:

Does performing the same act at a national scale make it moral? No.

Does routing it through an authorized institution eliminate dilution, the Cantillon effect, the wealth gap, or the decivilizing consequences? No.

Does calling it “monetary policy” instead of “counterfeiting” change its nature? No.

Does issuing money by keystroke rather than by mint transform the vice into a virtue? No.

Expanding the money supply without performing requisite productive work and perfect counterfeiting are mechanically the same whether by a central banker or Master Adam. Central banks create new money by buying government bonds or lowering interest rates to allow more money to be lent into existence. In Master Adam's time, counterfeiting meant diluting gold purity. Today, central banks create money with keystrokes, adding digits to accounts. The method differs, but is the outcome any different?

The Cantillon effect operates identically. Those closest to new money benefit most, typically financial institutions, while wage earners receive it last. The wealth gap widens as asset owners and debtors gain, while earners and savers lose purchasing power. And the decivilizing forces intensify, shifting incentives away from productive work toward leverage, speculation, and risk-taking.

Counterfeiting and unconstrained money supply expansion produce the same outcomes because they are the same sin: creating money without productive work, diluting everyone else’s holdings and systematically transferring value from the many to the few.

A central bank targeting 2% consumer price inflation expands the money supply 7% annually, compounding. The billions in new money (dollars, euros, pounds, etc…) created with a keystroke are indistinguishable from the money already in circulation. It’s perfect counterfeiting, money created without working and used to buy real things from real people. The difference between Master Adam and a modern central bank is legal authority and scale, not in terms of consequences of their actions.

Dante placed Master Adam in the eighth circle not because he lacked authorization, but because counterfeiting violates fundamental moral laws: thou shalt not lie, thou shalt not steal. These commandments contain no exception for scale, authority, method, or justification.

The Counterfeiter’s Defence

Imagine Master Adam tied to the stake, flames rising, shouting his defence: “I provided liquidity to the economy, I increased the velocity of money, and some of my coins went to the needy.”

Such justifications for money supply expansion ultimately fail.

The benefits are visible and immediate: transactions counted, commerce measured, and liquidity added. The costs, however, are invisible, delayed, and regressive: corrupted price signals, misallocated resources, destroyed savings, expanded wealth inequality, and incentives perverted. It may take time for these costs to be realized, but they inevitably will.

Even well-intentioned, philanthropic counterfeiting ultimately extracts from the poor to benefit the wealthy. Suppose Master Adam gave his fake florins to the poor, who buy bread and pay rent. New money flows into the economy, ultimately bidding up scarce assets faster than common goods. The poor receive temporary help with immediate needs but suffer permanent inflation as real wealth gets further out of reach.

Sound money benefits the poor, by allowing natural deflationary forces to make everything cheaper over time. Whether Master Adam keeps his counterfeit profits for himself or gives them to the poor, the results are ultimately damaging for everyone.

Eternal Truths

A thief with a knife steals openly. His victim knows immediately what was taken. Master Adam’s theft, by contrast, was silent, distributed, regressive, and caused unknowable damage.

“Monetary stimulus,” “Quantitative easing,” and “Reserve management,” are modern terms for arbitrary money supply expansion by sanctioned authorities. If the effects are identical to counterfeiting, if the damage is the same, can the acts really be so different? Does legal authority determine morality? Or can anyone see plainly that what is being done is wrong, regardless of its legal standing?

Creating money without productive work transfers value from those who earned it to those who printed it. This is theft, disguised with sophisticated language and conducted by prestigious institutions, but theft nonetheless. It flows regressively, from poor to rich, from earners to asset owners, from the powerless to the powerful. Those who need sound money most, suffer most.

But eternal truths remain eternal. Don’t lie. Don’t steal. Don’t cheat. Pursue productive work, discipline, honesty, and humility. These simple principles don’t bend to temporal power or sophisticated terminology.

Counterfeiting is counterfeiting, whether done in a medieval workshop or a central bank. The lie is still a lie. The theft is still theft. And the eighth circle still awaits.

Follow for more. Full content at scarcityandabundance.com .