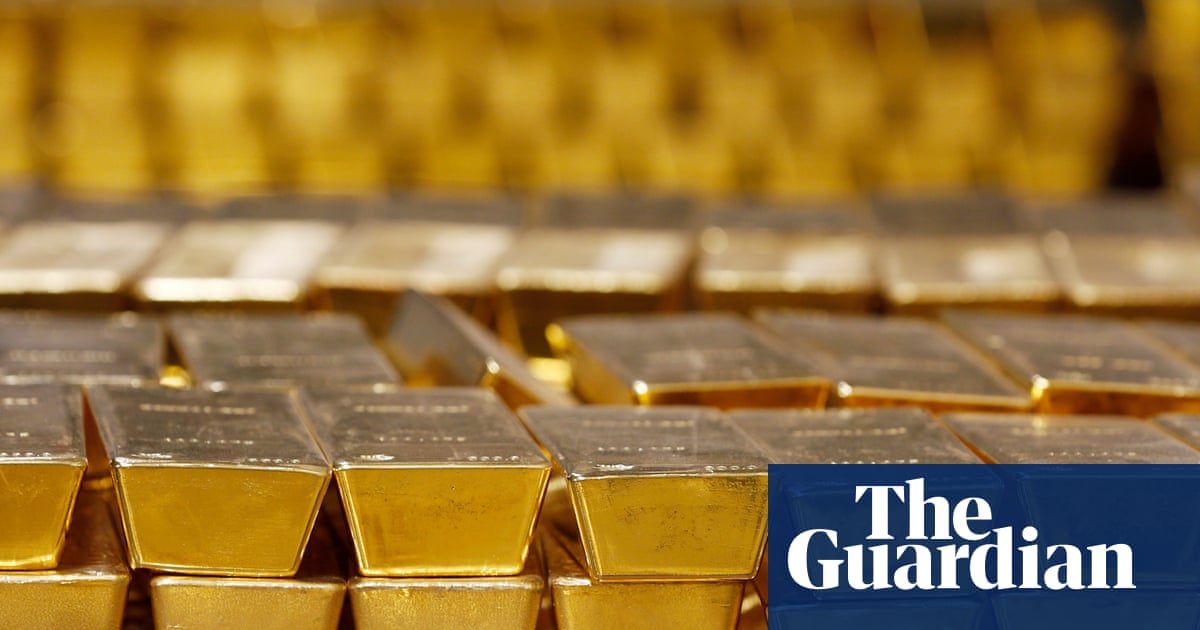

Gold just hit $4,643 an ounce. Analysts expect $5,000 this year. Central banks have doubled their gold holdings as a share of reserves over the past decade — the highest level in 30 years.

The system producing this outcome is straightforward.

The dollar has functioned as the global reserve currency for decades. That status depends on two things: institutional credibility and the perception that dollar-denominated assets are safe. Both are eroding. The Fed's independence is being publicly challenged. US fiscal health is deteriorating. And after Washington froze Russian central bank reserves post-invasion, every sovereign wealth manager on the planet updated their risk model.

The result: central banks are quietly moving out of dollars and into gold. Not because gold generates yield — it doesn't. But because gold is nobody's debt. It can't be frozen, sanctioned, or printed. In a world where reserve assets can be weaponized, the oldest store of value becomes the safest.

Gold overtook the euro as the second-largest reserve asset last year. The dollar's share of global reserves has slipped from 66% to 57% in a decade. Half of central banks surveyed plan to buy more.

The interesting part is not that this is happening. It's that there is no replacement for the dollar — no other fiat currency has the scale. So institutions are defaulting to what Keynes called the 'barbarous relic.' The monetary system is not transitioning to a new anchor. It is slowly losing its current one.

Source:

the Guardian

‘The dollar is losing credibility’: why central banks are scrambling for gold

Experts say central banks are increasingly stuffing their vaults as an insurance policy in a volatile world