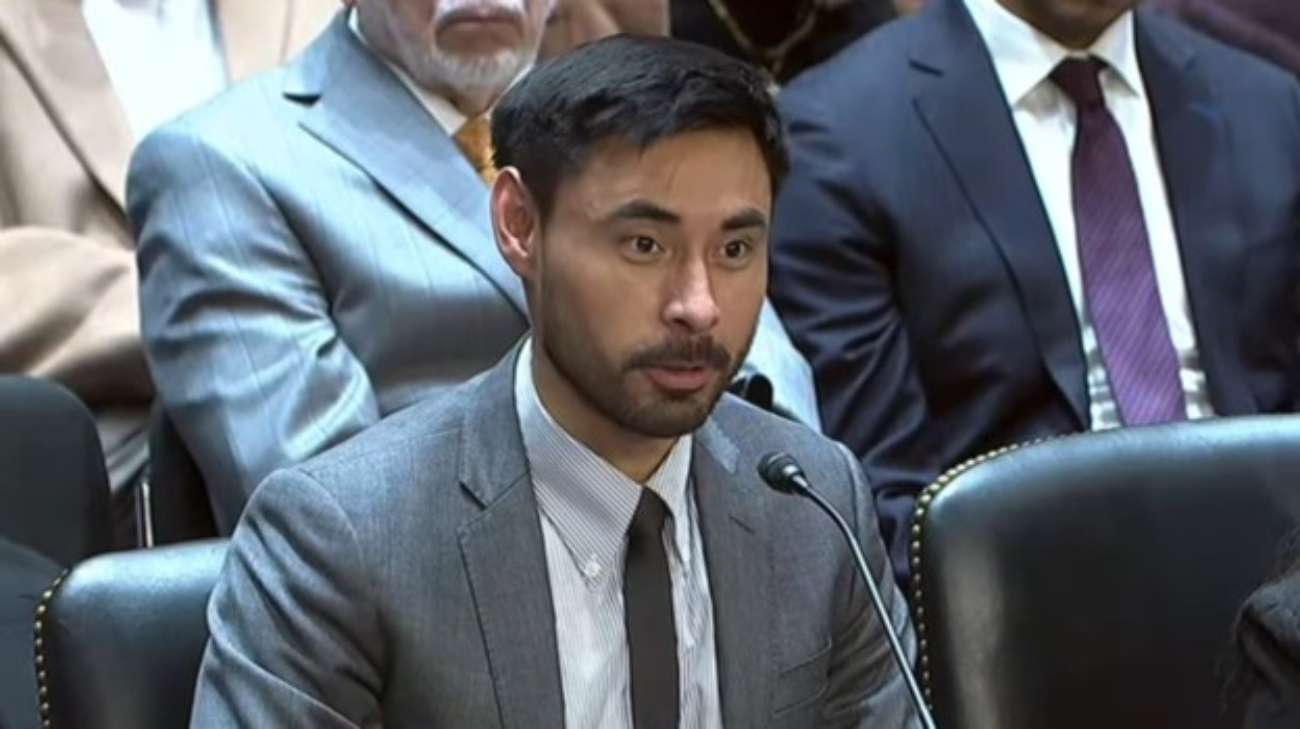

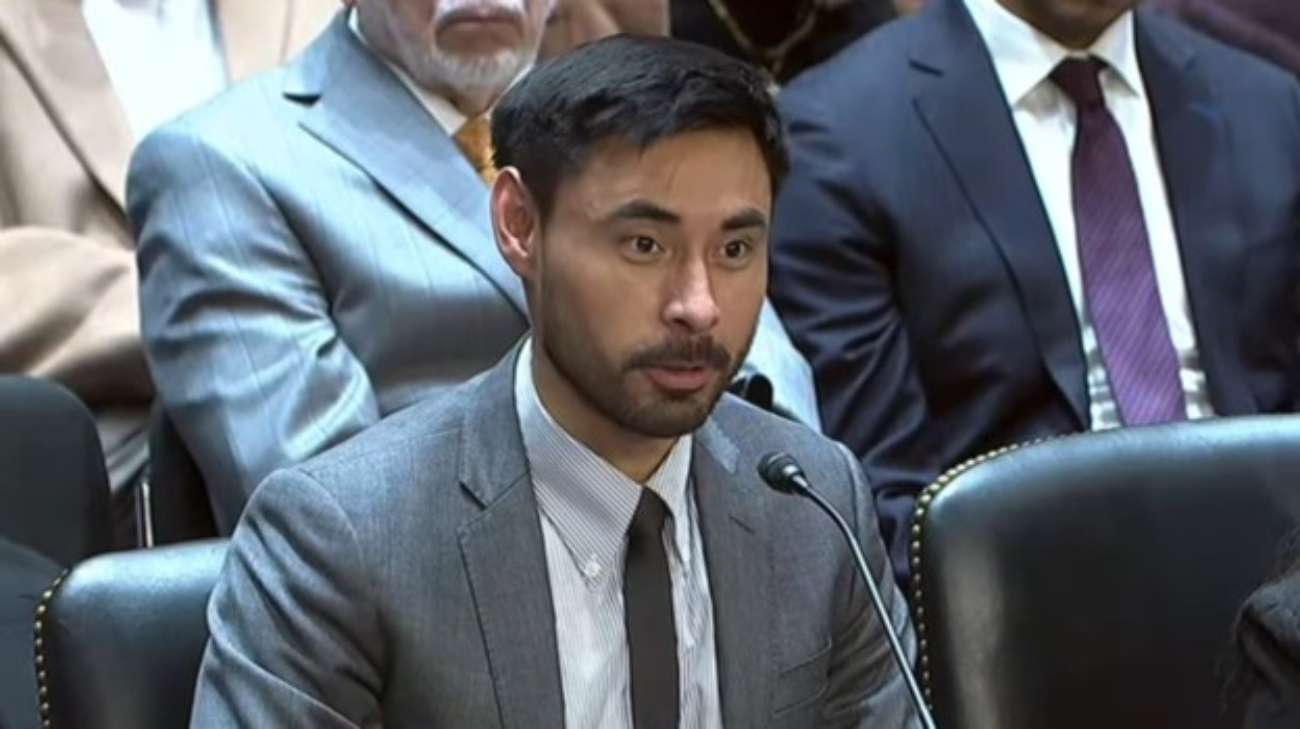

Last July, Wilmer Chavarria, a naturalized U.S. citizen who lives in Vermont,

was returning from Nicaragua, where he had visited his mother and other relatives,

when he was detained by Customs and Border Protection (CBP) agents at the George Bush Intercontinental Airport in Houston

for no apparent reason.

👉Chavarria was held for more than four hours and released only after he finally agreed to let the agents search his smartphone, tablet, and laptop computer.

The agents, who persistently pressured Chavarria to surrender his devices and the passwords for them, informed him that

⚠️he had no Fourth Amendment right to resist.

💥They were wrong about that,

the Pacific Legal Foundation (PLF) says in a lawsuit it filed in the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia on Wednesday against the Department of Homeland Security (DHS), which includes CBP.

✅ "Americans don't surrender their constitutional rights as the price of international travel," the PLF says.

"CBP policies that claim to give its employees the power to search and seize electronic devices without a warrant violate the Fourth Amendment and therefore should be set aside."

⭐️The Fourth Amendment guarantees "the right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects"

against "unreasonable searches and seizures."

It also specifies that judicial warrants, which are ordinarily required for searches, must be based on "probable cause" supported by "oath or affirmation" and must "particularly" describe the target of the search and "the persons or things to be seized."

The contents of electronic devices qualify as "papers" and "effects," PLF lawyers Amy Peikoff and Molly Nixon argue.

And although the Supreme Court has recognized a "border exception" to the Fourth Amendment, they say,

it cannot reasonably be understood to encompass the potentially vast amount of sensitive information that Americans routinely carry with them when they travel.

🆘Under the CBP's broad interpretation of the border exception, the PLF notes, federal agents are free to examine the contents of electronic devices anywhere within 100 miles of a U.S. border

—a zone that includes about two-thirds of the U.S. population.

They can do so at will without any articulable reason, let alone probable cause or a warrant.

And under CBP policy, they can copy and retain that information based on "a national security concern" or "reasonable suspicion of activity in violation of the laws enforced or administered by CBP," provided they obtain "supervisory approval."

"When Chavarria objected, he was told he had no Fourth Amendment rights at the border," the complaint says.

❌"Moreover, he was told he was behaving suspiciously simply by asserting those rights and refusing to consent to the device searches. His requests to contact his family and lawyer were denied during the detention."

Chavarria was especially concerned because the laptop he was carrying, which was the school district's property, contained student records.

But "after enduring hours of isolation, physical discomfort, threats, and badgering," the complaint says, Chavarria "finally succumb[ed] to the pressure and hand[ed] over his devices and passwords" based on the agents' "assurances that they would not access the student data on his laptop."

Because "the searches were conducted outside his presence," according to the lawsuit, Chavarria had no way of verifying that the agents kept their promise of self-restraint.

"Adding insult to injury, one of the plainclothes officers stopped Mr. Chavarria as he was being released to shake his hand and praise him for his resilience during the detention," the PLF says.

"Because of his unflinching commitment to his students' rights, the agent said he would be proud for his children to attend a school with a superintendent like Mr. Chavarria."

The border exception, which is meant to facilitate detection of contraband, weapons, customs violations, and illegal immigration, has traditionally applied to

"searches of persons entering the United States and their physical property," Peikoff and Nixon note.

Given the ubiquity of electronic devices and their storage capacity, extending the border exception to include the data they contain has profound privacy implications.

The upshot is that Americans commonly carry enormous amounts of data in their pockets and computer bags,

potentially including years of personal information about their habits, opinions, work, family life, relationships, and medical histories.

But ⛔️according to the CBP, its agents have plenary authority to peruse that information whenever they want

"with or without suspicion."

And if they have a "reasonable suspicion" of illegal activity,

which is supposed to be based on "specific, articulable facts"

but in practice may amount to little more than a hunch,

they also can copy information.

Reason.com

CBP agents held this U.S. citizen for hours until he agreed to let them search his electronic devices

A federal lawsuit argues that perusing travelers' personal data without a warrant or probable cause violates the Fourth Amendment.