Red candles come and go. History says relax.

Long before #Bitcoin existed, #HalFinney was keeping the #Cypherpunk dream alive. Even in the early 2000s, when many had lost hope that electronic cash would ever work, Finney refused to give up.

Hal wasn’t just an early #Bitcoiner, he was one of the most committed Cypherpunks. A video game developer from California and an early contributor to PGP, he reviewed almost every e-cash proposal the mailing list produced.

In 2004, he launched his own system: Reusable Proof of Work (#RPOW).

Like #Hashcash and #BitGold, RPOW used proof of work to create new value. Users would connect to a server operated by Finney, solve a PoW challenge, and receive an RPOW token. The server kept a database of issued tokens to prevent double spending.

To spend RPOW, you simply sent your token to someone else. They would then forward it to the RPOW server, which validated it and issued them a new one. In this way, proof of work became reusable.

Privacy was built in. All connections to the server went through Tor, so Hal never knew who his users were.

To guarantee honesty, Finney relied on open-source software and a new technique called “remote attestation.” The RPOW code ran on a special IBM chip that could cryptographically prove it was running the correct software, ensuring that no one, not even Hal, could secretly mint tokens.

Unlike Bit Gold, RPOW was actually implemented and ran in the real world. But it had one major flaw: as computers became faster, generating new RPOW tokens became easier. Over time, the currency would inflate.

There was no economic incentive to hold or accept it. Without that, RPOW never gained traction.

Finney had solved electronic cash on a technical level, but the economics weren’t right. Bitcoin would later fix that by aligning incentives with proof of work.

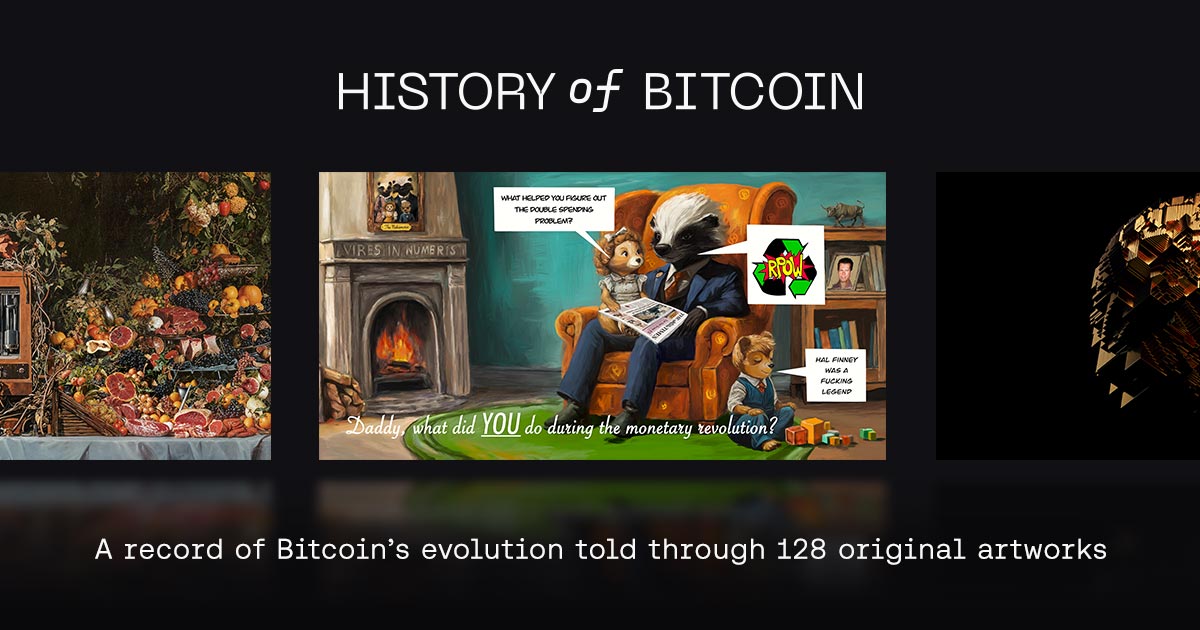

We honour this chapter in “The History of Bitcoin by Smashtoshi” with the artwork:

“REUSABLE WORK” by Yonat Vaks (@yonatvaks on X).

It appears in the History of Bitcoin Collector’s Book and on our interactive timeline.

Read the full article by Aaron van Wirdum:

History of Bitcoin

Reusable Work

Hal Finney’s Reusable Proof-of-Work (RPOW) introduced the idea of digital tokens backed by real-world resources, an early step toward Bitcoin’s...