I’m a huge fan of Dungeons of Sundaria.

This is a cooperative action RPG dungeon crawler built by Industry Games, a small independent studio out of Arizona. No procedural fluff. Just massive, hand-crafted dungeons designed to be suffered through with up to 4 players. It landed a full 1.0 release on December 12, 2023, across PC, PlayStation, Xbox, and Switch.

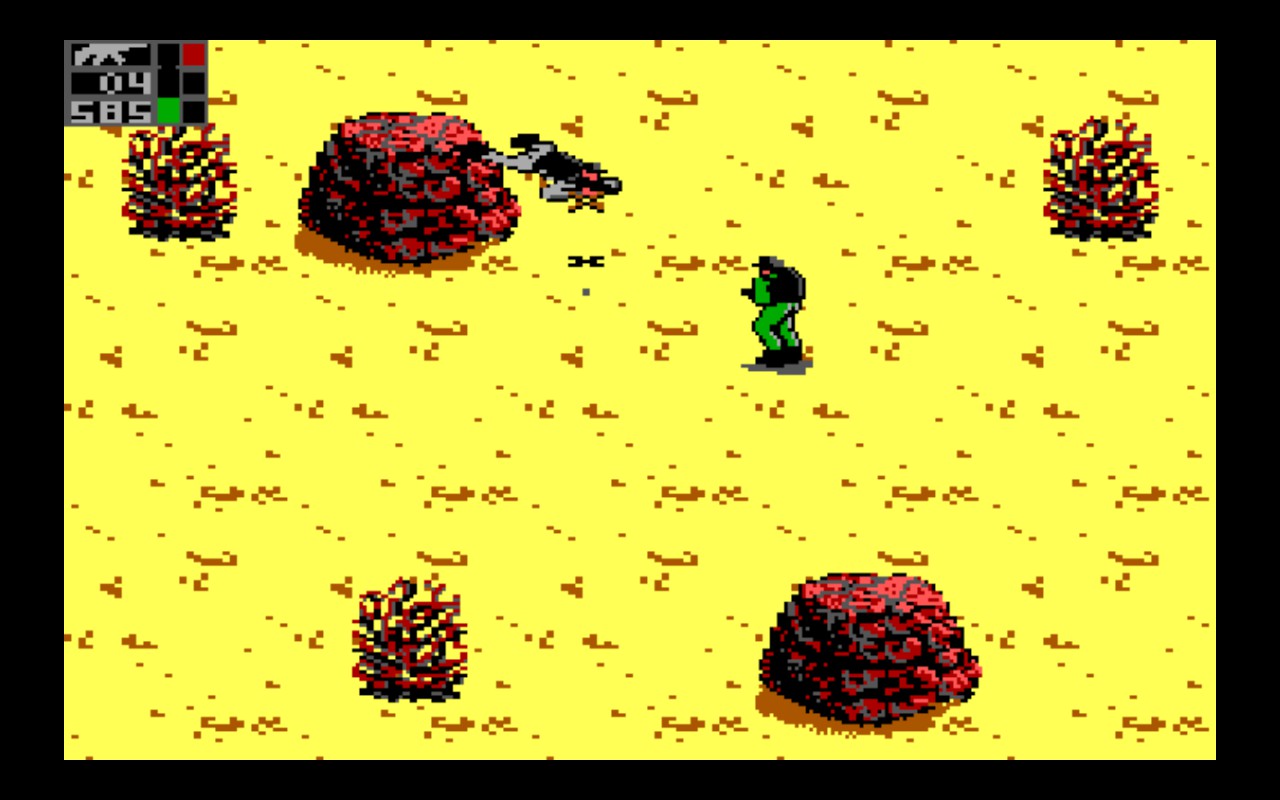

The dungeons are the entire point here. They are enormous, themed, and unapologetically long. This is not a 15-minute loot jog. You get checkpoints because the developers know what they’re doing to you. Enemy patrols, mines, stunlock nonsense, and bosses that absolutely do not care if you queued solo.

The combat is pure mayhem. Five classic classes—Champion, Cleric, Ranger, Rogue, Wizard—lean hard into old-school party roles. Co-op makes this plainly better. Positioning matters. Button-mashing alone will get you folded.

It reminds me a lot of Enclave—that early-2000s action RPG where you picked a class, entered isolated combat arenas, and survived on stiff melee, dodgy camera angles, and raw difficulty—but Dungeons of Sundaria takes that foundation, stretches it into massive continuous dungeons, cranks the hostility, and then actually rewards you with mountains of meaningful loot.

And yes, the loot. There is a lot of it. A ridiculous amount. The entire gameplay loop is opening doors, decimating monsters, and vacuuming up gear to make your character increasingly unhinged.

Finish a run, tweak your build, go back in harder. Post-max-level progression exists specifically so you don’t stop doing this.

This is not a AAA production. The graphics are dated. Animations can be stiff. The camera occasionally fights you, especially if you picked a smaller race.

None of this matters. The art direction is clear, readable, and easy on the eyes, which is exactly what you want when everything is trying to kill you at once.

People keep calling Dungeons of Sundaria an underrated gem, usually right after complaining about the grind and then loading another dungeon anyway.

The frequent deep discounts suggest it didn’t set the sales charts on fire. That tracks. This is a niche game for people who miss classic D&D-style dungeon crawls and don’t need cinematic hand-holding.

If you want spectacle, look elsewhere. If you want long, punishing dungeon runs, absurd loot, and a game that respects your ability to figure things out, Dungeons of Sundaria absolutely gets it.