Fork Smarter, Not Harder: CKB's Forking Philosophy Explained

1/ In most blockchains, hardforks often imply discontinuity, where:

😕 Users risk losing access to assets.

🤨 Developers are forced to upgrade—like it or not.

CKB takes a different approach: it decouples upgradeability from forced consensus.

🔐 Assets remain safe during upgrades.

⛓️ Users aren't forced to adopt new protocols.

Here's how it works:

2/ Protocol-Level Flexibility: Fork Without Split

CKB is built on the UTXO Cell model, where each user's assets are stored in the discrete Cells—each with its own versioned Lock Script.

After a hardfork, each Cell continues to use the VM version it was deployed with, where:

- Existing Cells remain on the old VM version.

- Users are not forced to upgrade the Scripts.

- They opt in new features — if and when they want to.

This is made possible by introducing multiple hash_type variants (type, data, data1, data2, ...), each pointing to a different version of the code.

🤝 Multiple versions of Scripts and VMs coexist on the same chain.

⛓️ Upgrades won't split the network.

🔐 Users keep full control over both the assets, and the rules that govern them as well.

3/ Why It Matters 💡

Most chains treat a hardfork as a reset — override old logic and force everyone to upgrade.

CKB avoids this.

Multiple versions run side by side on the same chain. This eliminates the tension between network evolution and asset preservation.

4/ Script-Level Upgrade Workflow: Type ID + Lock Script

CKB provides Type ID + Lock Script model for managing script upgrades:

1️⃣ Initial Deployment: A Script developer deploys Scripts with upgrade plans in mind: Using Type ID to assign a stable identity but allows future updates.

2️⃣ Iterative Upgrade: Fix bugs, add new features, and change rules—the deployed code may undergo several upgrades using Type ID.

3️⃣ Code Freezing: At any point, one can freeze the code by modifying the Lock Script to be immutable.

5/ Script Developer & dApp Developer: Separate Roles

CKB separates two responsibilities:

- Script Developers: Deploy the Script and decide if it is upgradeable, via Type ID + Lock Script.

- dApp Developers: Choose how to reference a Script in their applications—fixed or upgradable.

Their options:

🔹Reference by type hash → Auto-follow the latest upgrades

🔹Reference by data / data1 / data2 hash → Stay fixed to the trusted version, ignoring the new one

Either way, dApp devs don't need to fear upstream changes breaking their logic or being kicked out of the network.

6/

This separation enables:

- Reusable Scripts across multiple dApps

- Opt-in upgrades — no forced coordination

- Long-term stability where needed, flexibility where desired

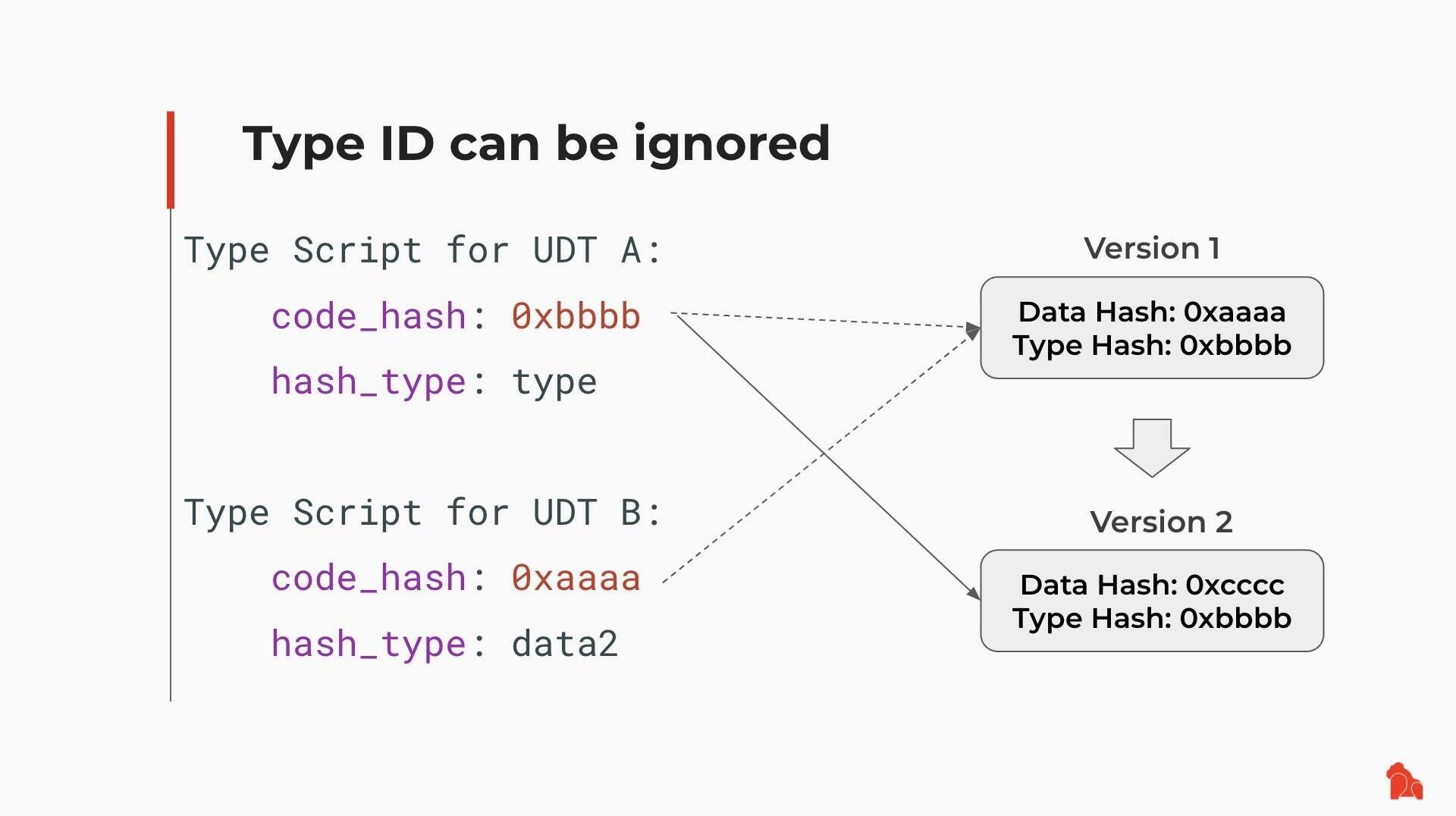

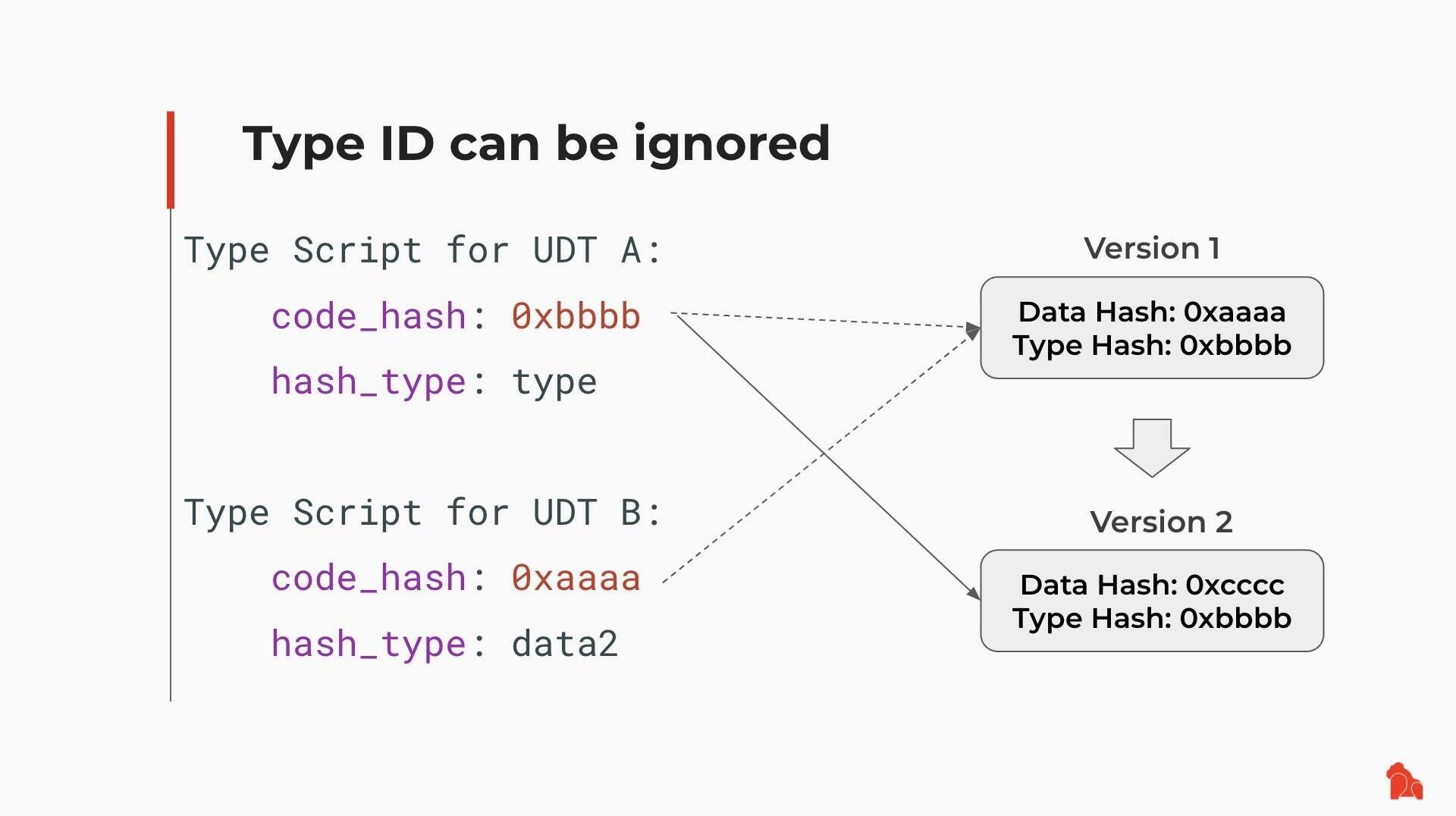

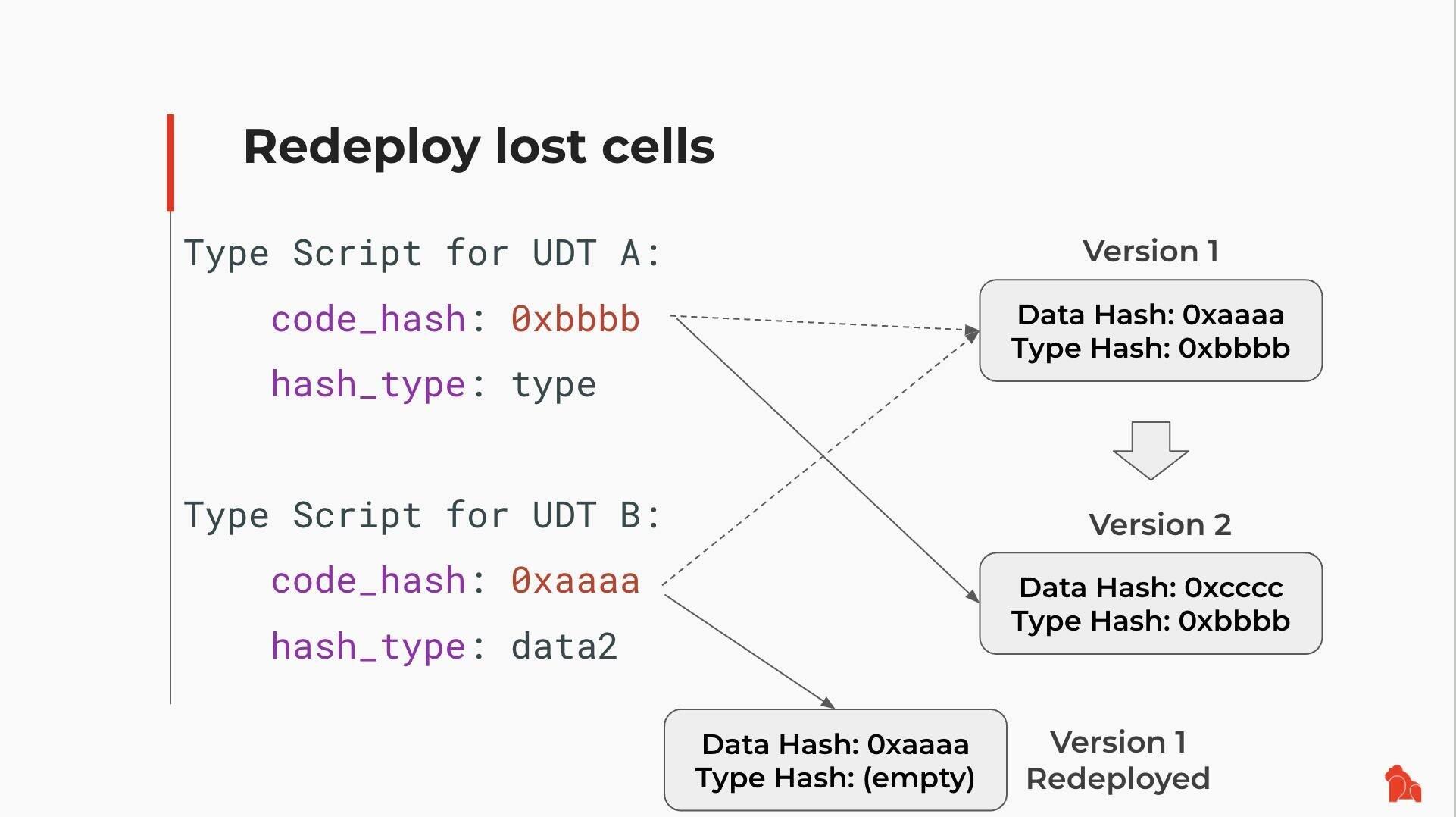

7/ Example: UDT Script Upgrade

Suppose someone deployed a UDT (User-Defined Token) Script using Type ID and created two tokens:

- UDT A uses type as hash_type

- UDT B uses data2 as hash_type

Later, the UDT Script is upgraded from Version 1 to Version 2:

- UDT A automatically adopts Version 2

- UDT B keeps running on Version 1

Here's how it works:

2/ Protocol-Level Flexibility: Fork Without Split

CKB is built on the UTXO Cell model, where each user's assets are stored in the discrete Cells—each with its own versioned Lock Script.

After a hardfork, each Cell continues to use the VM version it was deployed with, where:

- Existing Cells remain on the old VM version.

- Users are not forced to upgrade the Scripts.

- They opt in new features — if and when they want to.

This is made possible by introducing multiple hash_type variants (type, data, data1, data2, ...), each pointing to a different version of the code.

🤝 Multiple versions of Scripts and VMs coexist on the same chain.

⛓️ Upgrades won't split the network.

🔐 Users keep full control over both the assets, and the rules that govern them as well.

3/ Why It Matters 💡

Most chains treat a hardfork as a reset — override old logic and force everyone to upgrade.

CKB avoids this.

Multiple versions run side by side on the same chain. This eliminates the tension between network evolution and asset preservation.

4/ Script-Level Upgrade Workflow: Type ID + Lock Script

CKB provides Type ID + Lock Script model for managing script upgrades:

1️⃣ Initial Deployment: A Script developer deploys Scripts with upgrade plans in mind: Using Type ID to assign a stable identity but allows future updates.

2️⃣ Iterative Upgrade: Fix bugs, add new features, and change rules—the deployed code may undergo several upgrades using Type ID.

3️⃣ Code Freezing: At any point, one can freeze the code by modifying the Lock Script to be immutable.

5/ Script Developer & dApp Developer: Separate Roles

CKB separates two responsibilities:

- Script Developers: Deploy the Script and decide if it is upgradeable, via Type ID + Lock Script.

- dApp Developers: Choose how to reference a Script in their applications—fixed or upgradable.

Their options:

🔹Reference by type hash → Auto-follow the latest upgrades

🔹Reference by data / data1 / data2 hash → Stay fixed to the trusted version, ignoring the new one

Either way, dApp devs don't need to fear upstream changes breaking their logic or being kicked out of the network.

6/

This separation enables:

- Reusable Scripts across multiple dApps

- Opt-in upgrades — no forced coordination

- Long-term stability where needed, flexibility where desired

7/ Example: UDT Script Upgrade

Suppose someone deployed a UDT (User-Defined Token) Script using Type ID and created two tokens:

- UDT A uses type as hash_type

- UDT B uses data2 as hash_type

Later, the UDT Script is upgraded from Version 1 to Version 2:

- UDT A automatically adopts Version 2

- UDT B keeps running on Version 1

8/

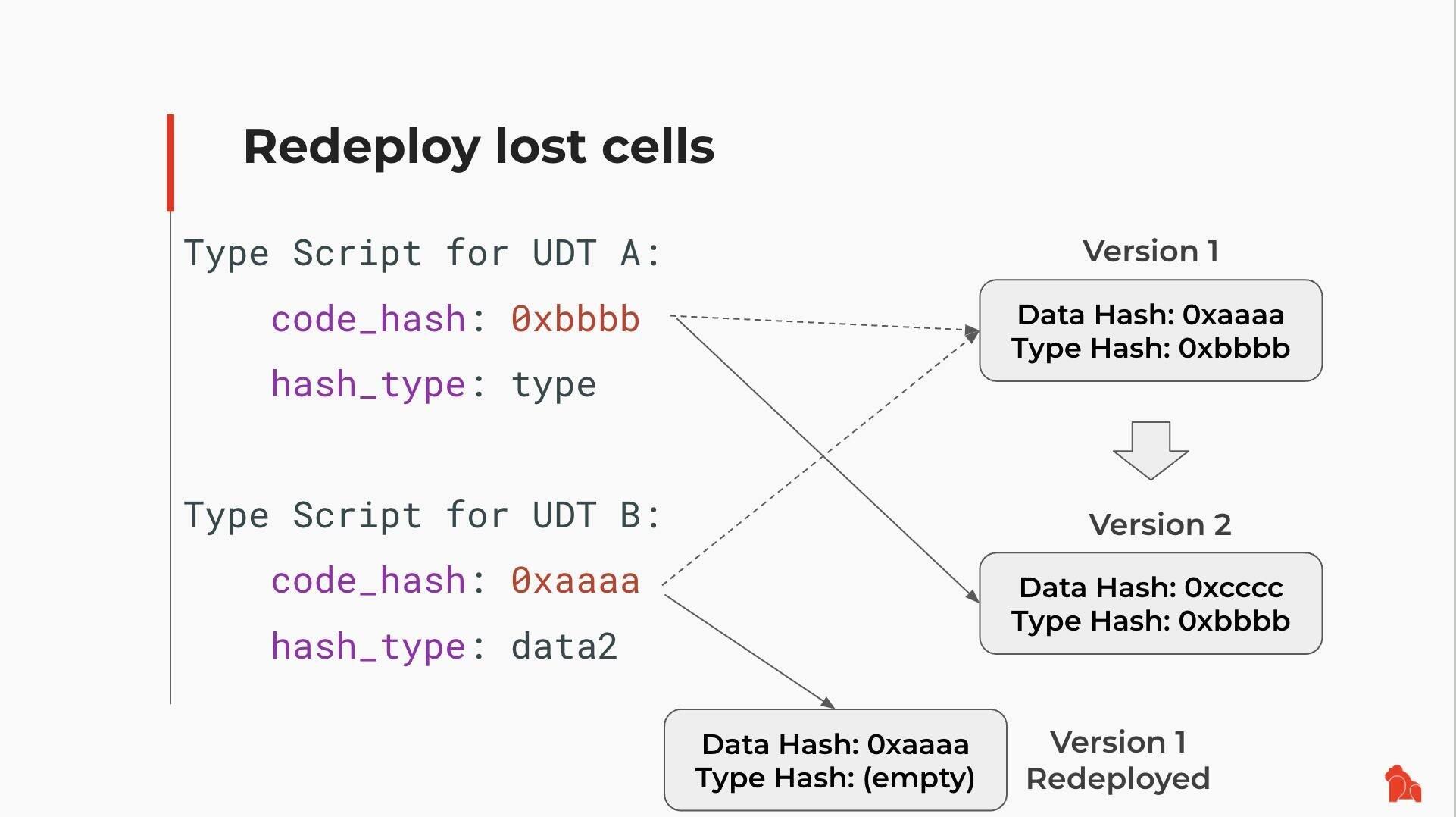

Even if Version 1 is no longer present in a live Cell, it's not lost.

You can retrieve it from chain history, redeploy it, and use it again.

Old logic remains accessible—by design.

8/

Even if Version 1 is no longer present in a live Cell, it's not lost.

You can retrieve it from chain history, redeploy it, and use it again.

Old logic remains accessible—by design.

9/ A Better Forking Philosophy

CKB doesn't follow the rigid "hard vs. soft forks" binary. Instead, it offers:

✅ User autonomy

✅ Developer control

Assets stay protected.

Scripts remain stable—or upgradeable.

No one is forced to choose between safety and progress.

It's a better way to fork. And it works.

10/ Reference Links

Rethinking Forks: The Philosophy Behind CKB's Network Upgrade Design:

Recommended Workflow for Script Upgrades:

How CKB Turns User Defined Cryptos Into First-Class Assets: https://blog.cryptape.com/how-ckb-turns-user-defined-cryptos-into-first-class-assets

CKB, Version Control and Blockchain Evolution:

9/ A Better Forking Philosophy

CKB doesn't follow the rigid "hard vs. soft forks" binary. Instead, it offers:

✅ User autonomy

✅ Developer control

Assets stay protected.

Scripts remain stable—or upgradeable.

No one is forced to choose between safety and progress.

It's a better way to fork. And it works.

10/ Reference Links

Rethinking Forks: The Philosophy Behind CKB's Network Upgrade Design:

Recommended Workflow for Script Upgrades:

How CKB Turns User Defined Cryptos Into First-Class Assets: https://blog.cryptape.com/how-ckb-turns-user-defined-cryptos-into-first-class-assets

CKB, Version Control and Blockchain Evolution:  CKB VM Version Selection: .md

CKB VM Version Selection: .md

Here's how it works:

2/ Protocol-Level Flexibility: Fork Without Split

CKB is built on the UTXO Cell model, where each user's assets are stored in the discrete Cells—each with its own versioned Lock Script.

After a hardfork, each Cell continues to use the VM version it was deployed with, where:

- Existing Cells remain on the old VM version.

- Users are not forced to upgrade the Scripts.

- They opt in new features — if and when they want to.

This is made possible by introducing multiple hash_type variants (type, data, data1, data2, ...), each pointing to a different version of the code.

🤝 Multiple versions of Scripts and VMs coexist on the same chain.

⛓️ Upgrades won't split the network.

🔐 Users keep full control over both the assets, and the rules that govern them as well.

3/ Why It Matters 💡

Most chains treat a hardfork as a reset — override old logic and force everyone to upgrade.

CKB avoids this.

Multiple versions run side by side on the same chain. This eliminates the tension between network evolution and asset preservation.

4/ Script-Level Upgrade Workflow: Type ID + Lock Script

CKB provides Type ID + Lock Script model for managing script upgrades:

1️⃣ Initial Deployment: A Script developer deploys Scripts with upgrade plans in mind: Using Type ID to assign a stable identity but allows future updates.

2️⃣ Iterative Upgrade: Fix bugs, add new features, and change rules—the deployed code may undergo several upgrades using Type ID.

3️⃣ Code Freezing: At any point, one can freeze the code by modifying the Lock Script to be immutable.

5/ Script Developer & dApp Developer: Separate Roles

CKB separates two responsibilities:

- Script Developers: Deploy the Script and decide if it is upgradeable, via Type ID + Lock Script.

- dApp Developers: Choose how to reference a Script in their applications—fixed or upgradable.

Their options:

🔹Reference by type hash → Auto-follow the latest upgrades

🔹Reference by data / data1 / data2 hash → Stay fixed to the trusted version, ignoring the new one

Either way, dApp devs don't need to fear upstream changes breaking their logic or being kicked out of the network.

6/

This separation enables:

- Reusable Scripts across multiple dApps

- Opt-in upgrades — no forced coordination

- Long-term stability where needed, flexibility where desired

7/ Example: UDT Script Upgrade

Suppose someone deployed a UDT (User-Defined Token) Script using Type ID and created two tokens:

- UDT A uses type as hash_type

- UDT B uses data2 as hash_type

Later, the UDT Script is upgraded from Version 1 to Version 2:

- UDT A automatically adopts Version 2

- UDT B keeps running on Version 1

Here's how it works:

2/ Protocol-Level Flexibility: Fork Without Split

CKB is built on the UTXO Cell model, where each user's assets are stored in the discrete Cells—each with its own versioned Lock Script.

After a hardfork, each Cell continues to use the VM version it was deployed with, where:

- Existing Cells remain on the old VM version.

- Users are not forced to upgrade the Scripts.

- They opt in new features — if and when they want to.

This is made possible by introducing multiple hash_type variants (type, data, data1, data2, ...), each pointing to a different version of the code.

🤝 Multiple versions of Scripts and VMs coexist on the same chain.

⛓️ Upgrades won't split the network.

🔐 Users keep full control over both the assets, and the rules that govern them as well.

3/ Why It Matters 💡

Most chains treat a hardfork as a reset — override old logic and force everyone to upgrade.

CKB avoids this.

Multiple versions run side by side on the same chain. This eliminates the tension between network evolution and asset preservation.

4/ Script-Level Upgrade Workflow: Type ID + Lock Script

CKB provides Type ID + Lock Script model for managing script upgrades:

1️⃣ Initial Deployment: A Script developer deploys Scripts with upgrade plans in mind: Using Type ID to assign a stable identity but allows future updates.

2️⃣ Iterative Upgrade: Fix bugs, add new features, and change rules—the deployed code may undergo several upgrades using Type ID.

3️⃣ Code Freezing: At any point, one can freeze the code by modifying the Lock Script to be immutable.

5/ Script Developer & dApp Developer: Separate Roles

CKB separates two responsibilities:

- Script Developers: Deploy the Script and decide if it is upgradeable, via Type ID + Lock Script.

- dApp Developers: Choose how to reference a Script in their applications—fixed or upgradable.

Their options:

🔹Reference by type hash → Auto-follow the latest upgrades

🔹Reference by data / data1 / data2 hash → Stay fixed to the trusted version, ignoring the new one

Either way, dApp devs don't need to fear upstream changes breaking their logic or being kicked out of the network.

6/

This separation enables:

- Reusable Scripts across multiple dApps

- Opt-in upgrades — no forced coordination

- Long-term stability where needed, flexibility where desired

7/ Example: UDT Script Upgrade

Suppose someone deployed a UDT (User-Defined Token) Script using Type ID and created two tokens:

- UDT A uses type as hash_type

- UDT B uses data2 as hash_type

Later, the UDT Script is upgraded from Version 1 to Version 2:

- UDT A automatically adopts Version 2

- UDT B keeps running on Version 1

8/

Even if Version 1 is no longer present in a live Cell, it's not lost.

You can retrieve it from chain history, redeploy it, and use it again.

Old logic remains accessible—by design.

8/

Even if Version 1 is no longer present in a live Cell, it's not lost.

You can retrieve it from chain history, redeploy it, and use it again.

Old logic remains accessible—by design.

9/ A Better Forking Philosophy

CKB doesn't follow the rigid "hard vs. soft forks" binary. Instead, it offers:

✅ User autonomy

✅ Developer control

Assets stay protected.

Scripts remain stable—or upgradeable.

No one is forced to choose between safety and progress.

It's a better way to fork. And it works.

10/ Reference Links

Rethinking Forks: The Philosophy Behind CKB's Network Upgrade Design:

9/ A Better Forking Philosophy

CKB doesn't follow the rigid "hard vs. soft forks" binary. Instead, it offers:

✅ User autonomy

✅ Developer control

Assets stay protected.

Scripts remain stable—or upgradeable.

No one is forced to choose between safety and progress.

It's a better way to fork. And it works.

10/ Reference Links

Rethinking Forks: The Philosophy Behind CKB's Network Upgrade Design: Rethinking Forks | Nervos CKB

Originally written by Jan Xie

Upgrade Scripts | Nervos CKB

This article is based on ideas presented in this talk by Xuejie Xiao

Nervos Talk

CKB, Version Control and Blockchain Evolution

I’m Linus’s fan. This guy created an open-source operating system running everywhere, co-authored a book which is one of my favorites, and buil...

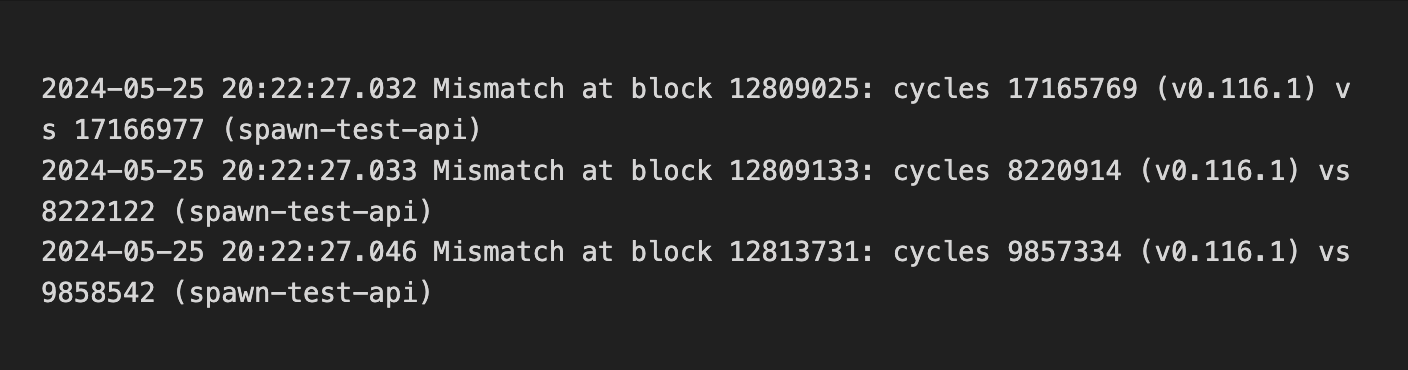

1/ Initial Verification: Transaction Replay 🔁

We began by replaying historical on-chain transactions (via `replay`) from mainnet and testnet to check if `cycle` consumption remained consistent in the upgraded CKB-VM.

This caught several mismatches:

1/ Initial Verification: Transaction Replay 🔁

We began by replaying historical on-chain transactions (via `replay`) from mainnet and testnet to check if `cycle` consumption remained consistent in the upgraded CKB-VM.

This caught several mismatches:

As the chain only contains valid transactions, this method verifies past compatibility but not future cases. To broaden coverage, we turned to fuzzing to simulate diverse transaction inputs and assess compatibility across versions, including error handling in invalid transactions.

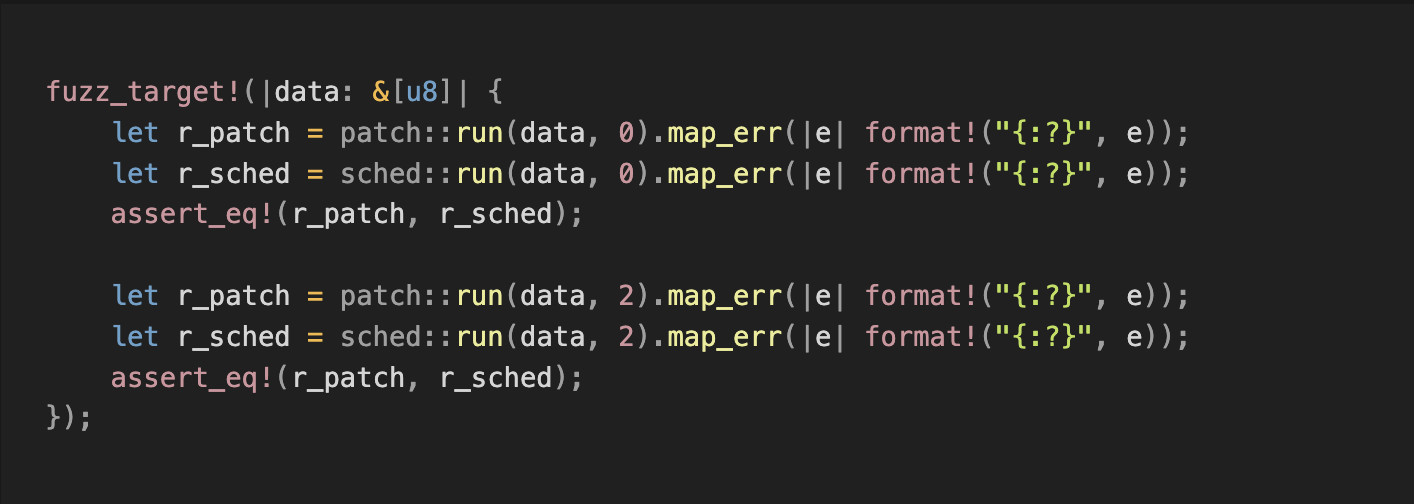

2/ First Fuzzing Attempt 🧪

We compared the execution results of `data0` and `data1` of the pre- and post-upgrade VM versions:

As the chain only contains valid transactions, this method verifies past compatibility but not future cases. To broaden coverage, we turned to fuzzing to simulate diverse transaction inputs and assess compatibility across versions, including error handling in invalid transactions.

2/ First Fuzzing Attempt 🧪

We compared the execution results of `data0` and `data1` of the pre- and post-upgrade VM versions:

However, most generated test cases were invalid. The test only compared whether the errors matched, but skipped the cycle consumption for valid cases—not enough to meet our goals.

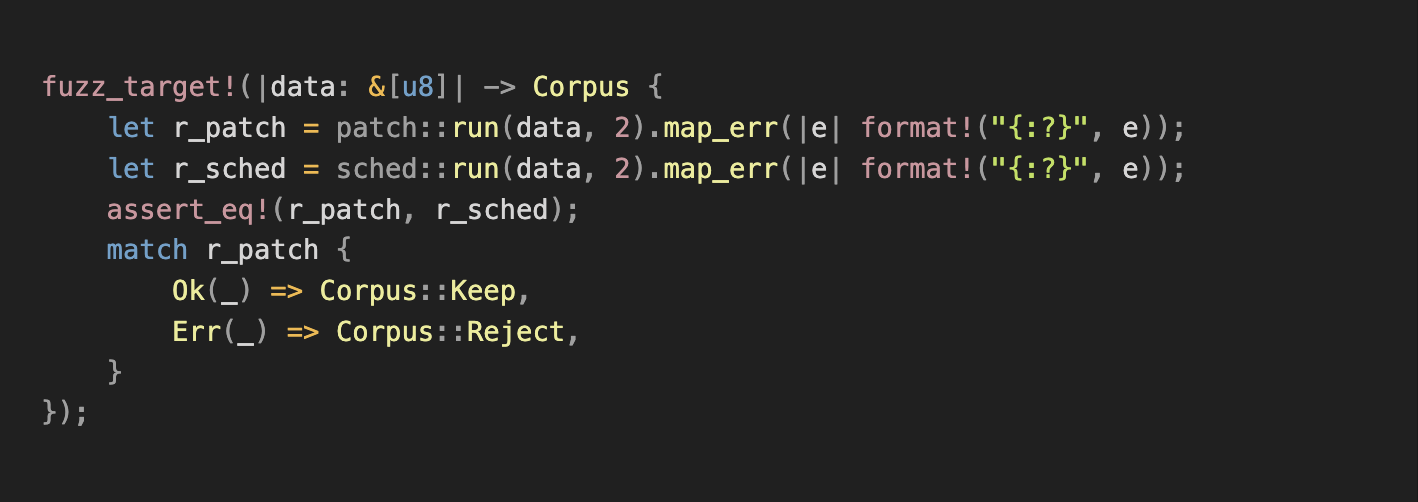

3/ Improved Fuzzing 🔧

To increase valid transaction input coverage, we refined the strategy:

- Corpus Optimization: Added valid transaction data from CKB-VM tests and CKB debugger binaries to the fuzzing corpus.

- Input Filtering: Modified fuzzing logic to only keep valid transactions in the corpus, further increasing the frequency of valid samples and enhancing `cycle` verification.

However, most generated test cases were invalid. The test only compared whether the errors matched, but skipped the cycle consumption for valid cases—not enough to meet our goals.

3/ Improved Fuzzing 🔧

To increase valid transaction input coverage, we refined the strategy:

- Corpus Optimization: Added valid transaction data from CKB-VM tests and CKB debugger binaries to the fuzzing corpus.

- Input Filtering: Modified fuzzing logic to only keep valid transactions in the corpus, further increasing the frequency of valid samples and enhancing `cycle` verification.

4/ Findings 😃

Improved fuzzing uncovered bugs, including:

- Crash caused by an invalid syscall parameter. Fix: github.com/libraries/ckb/commit/38279e118d3fda3c52f1d47d2062f80e19a2d523

- Instruction reordering led to mismatched `cycle` cost and memory out-of-bounds errors. Fix: github.com/libraries/ckb/commit/ea4aea7fa4cd87ce5df6dee6616466458ff5a86e

- Inconsistent error handling due to mismatched `DataPieceId` behavior. Fix: github.com/libraries/ckb/commit/af87dd355a653eaca19a643866300cc5cd907cf5

- Address truncation in x64. Fix: github.com/nervosnetwork/ckb-vm/commit/f6df535bbf8864fd14684c133b1aa8026a0b0868

- Inconsistencies in memory tracking. Fix: github.com/nervosnetwork/ckb-vm/commit/065a6457d06aa17da4f7dfa1954a2601fc7d288b

All issues were reproduced, analyzed, and added to the test corpus and the fuzzing crash directory for regression testing.

5/ Went Deeper: ISA-Level Fuzzing 🦾

In addition to compatibility testing, we fuzzed the instruction set to prevent unexpected VM panics.

See: github.com/nervosnetwork/ckb-vm-fuzzing-test

6/ Fuzzing isn’t flashy, but it pays off. 🛡️

As we know reliability is what gives developers confidence to build.

We’ll gladly keep things safe and steady—and maybe a little boring—so you don’t have to. 😎

8/ Reference Links 🔗

Fuzzing and tools:

- github.com/nervosnetwork/ckb-vm/tree/develop/fuzz

- github.com/libraries/schedfuzz

- github.com/nervosnetwork/ckb-vm-fuzzing-test

On VM 2:

- github.com/nervosnetwork/rfcs/blob/master/rfcs/0049-ckb-vm-version-2/0049-ckb-vm-version-2.md

4/ Findings 😃

Improved fuzzing uncovered bugs, including:

- Crash caused by an invalid syscall parameter. Fix: github.com/libraries/ckb/commit/38279e118d3fda3c52f1d47d2062f80e19a2d523

- Instruction reordering led to mismatched `cycle` cost and memory out-of-bounds errors. Fix: github.com/libraries/ckb/commit/ea4aea7fa4cd87ce5df6dee6616466458ff5a86e

- Inconsistent error handling due to mismatched `DataPieceId` behavior. Fix: github.com/libraries/ckb/commit/af87dd355a653eaca19a643866300cc5cd907cf5

- Address truncation in x64. Fix: github.com/nervosnetwork/ckb-vm/commit/f6df535bbf8864fd14684c133b1aa8026a0b0868

- Inconsistencies in memory tracking. Fix: github.com/nervosnetwork/ckb-vm/commit/065a6457d06aa17da4f7dfa1954a2601fc7d288b

All issues were reproduced, analyzed, and added to the test corpus and the fuzzing crash directory for regression testing.

5/ Went Deeper: ISA-Level Fuzzing 🦾

In addition to compatibility testing, we fuzzed the instruction set to prevent unexpected VM panics.

See: github.com/nervosnetwork/ckb-vm-fuzzing-test

6/ Fuzzing isn’t flashy, but it pays off. 🛡️

As we know reliability is what gives developers confidence to build.

We’ll gladly keep things safe and steady—and maybe a little boring—so you don’t have to. 😎

8/ Reference Links 🔗

Fuzzing and tools:

- github.com/nervosnetwork/ckb-vm/tree/develop/fuzz

- github.com/libraries/schedfuzz

- github.com/nervosnetwork/ckb-vm-fuzzing-test

On VM 2:

- github.com/nervosnetwork/rfcs/blob/master/rfcs/0049-ckb-vm-version-2/0049-ckb-vm-version-2.md